I’ve never been good at anger management. When I was a teenager, I had a French dictionary that I used to throw against the wall anytime I was angry. By the time I had finished high school, that dictionary looked like it had been through a war. At the same time, I’ve always had good friends and partners who did what good friends and partners are supposed to do: tell you uncomfortable truths that you need to hear. A big focus of our confrontations was how my anger affected them and our interactions. I said hurtful things I didn’t mean, I snapped over minor setbacks and, to make matters worse, I dismissed any criticism about my temper, denying to myself and others that it was a problem. I blamed it all on my Italian upbringing, laughing it off as a stereotypical quirk of the southern European ‘hot tempered’ woman.

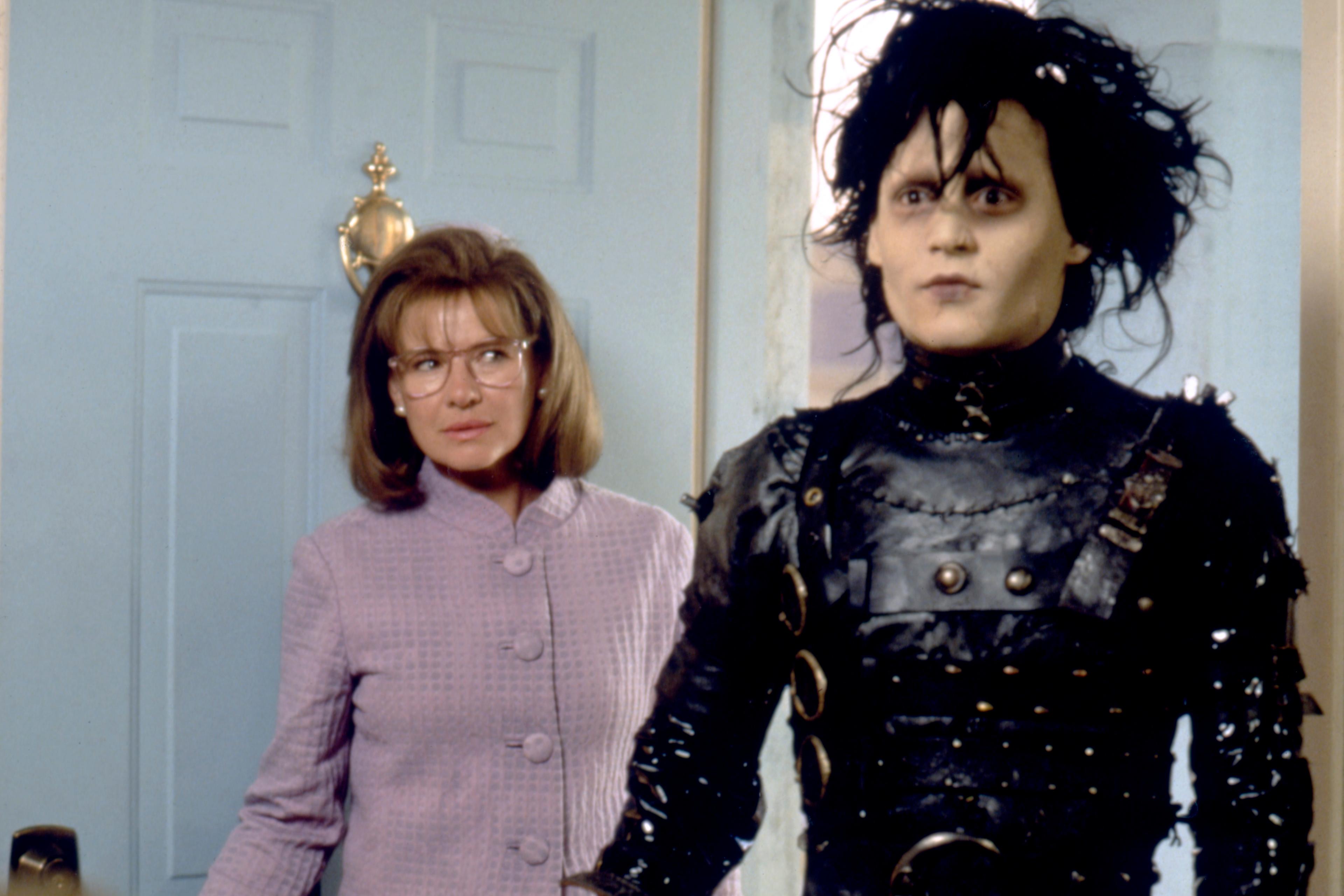

When I watched the TV series The Sopranos for the first time, I felt vindicated: virtually every character has anger issues. That was until I saw the episode in which Tony Soprano’s sister, Janice, in an explosion of rage, punches another woman at a children’s soccer game and gets arrested. True, even in my most explosive moments of anger, I had never assaulted anybody or ended up in jail (though there’s still time). But something clicked when I watched the following scene: Janice’s husband, exasperated by her temper, talks to her with an open heart and begs her to see an anger specialist, telling her that they ‘can’t live like this’. The similarities between Janice’s anger issues and my own became clear, because in watching that scene I empathised, for the first time, with someone who was at the receiving end of the anger – Janice’s husband. Empathising with his pain and compassion snapped me out of my denial. I saw clearly that uncontrolled anger can hurt those we love, and that it is ultimately our responsibility to manage our emotions.

My friends and my partner were glad to hear about my epiphany, but they wondered why it took having to empathise with a fictional character for me to finally come to my senses. I wondered that too, especially as someone who has dedicated years to studying how and why people deceive themselves. Why was The Sopranos successful in making me face my faults, but my loved ones’ call-outs weren’t?

My experience isn’t an isolated case. People often have sudden insights about themselves, but empathy seems to be a much more effective tool than reasoning for getting there. When another person points out the flaws in your behaviour, your first inclination might be to push back and make excuses for yourself. This is the phenomenon known as rationalisation, in which people shield themselves from taking criticism seriously by erecting a scaffolding of biased reasons against it. The philosopher Jason D’Cruz gives some typical examples:

It’s not cheating because everyone else is doing it too. I didn’t report the abuse because it wasn’t my place. I understated my income this year because I paid too much in tax last year. I’m only a social smoker, so I won’t get cancer.

This is exactly the kind of reaction I had when talking to my friends about my anger issues. Their frustration stemmed from the fact that rationalisation is extremely difficult to break through, as anybody who has ever reasoned with a defensive interlocutor will know. It is not just that nobody likes to admit their faults. When someone engages in rationalisation, every reason for criticism can in principle be met with another reason for dismissal, over and over again. The stronger the criticism, the more incessant the pushback: when rationalising, you can always find one more reason, one more excuse.

Considering this tendency that many of us have toward psychological self-defence in the face of criticism, we can start to see why empathy might provide a better avenue for understanding personal faults. The philosopher Gregory Currie has examined the implications of how fiction encourages us to imagine a character’s experience. If a character in a film or novel is grieving, for instance, you might find yourself taking on what you imagine to be their thoughts, desires and emotional pain, as if they were your own. This is an important part of engaging with narrative, one that Currie suggests could have moral consequences. The psychologists Geoff Kaufman and Lisa Libby have similarly observed that, when reading a narrative, people can lose themselves in the story to the point of ‘simulating’ and taking on the mindset of a character. When we do this, we can actually lose touch with ourselves, in a sense – not that our identity leaves us completely, but we are able to temporarily set it aside and experience the story as though we were someone else.

An interesting aspect of this ‘experience-taking’ is that it seems to bypass rational reasoning. And this is likely why empathising with fictional characters can be a useful tool for gaining insight into personal flaws. When confronted by a loved one about a fault, you might instinctively push back with an argument for why they are wrong. But experience-taking is immersive: it doesn’t confront you with reasoning, but rather transports you into a narrative world, where you can temporarily mute your self-related beliefs and desires as you adopt a character’s perspective instead. This immersion could be what undercuts the defensiveness that rational criticism might trigger. It puts us, for a moment, on the same side as the person who would criticise us and makes it easier to see why.

Homer Simpson realises that, like Blanche’s husband, he hasn’t been a good partner

This can happen in a variety of ways. When I bought Michelle Zauner’s acclaimed book Crying in H Mart (2021), a memoir about, among other things, her conflictual relationship with her parents, I expected to identify with her as I, too, have had difficult phases with my parents. What I did not expect was that I would empathise with her mother. Reading about how her mother courageously battled a terrible illness – and how Zauner decided to temporarily put her life on hold to support her mother – made me realise my own shortcomings as a daughter; all those times I refused to give my mother any grace, forgetting that relationships are complex and deserve to be handled with nuance.

Because it cuts through our rational filters and allows us to immerse ourselves in the story, fiction also has the power of inviting us to empathise with characters whose perspective we would not normally take on. As it happens, another work of fiction – an episode of the animated series The Simpsons – offers a helpful illustration. When Marge wins the role of Blanche in a community-theatre version of A Streetcar Named Desire, she is excited, but Homer is not. He shows little interest and refuses to practise lines with her. When she calls out Homer on his behaviour, he seems oblivious to his faults. But when the play debuts, and Homer watches as Blanche is mistreated by her husband, he empathises with Blanche’s pain and realises that, like Blanche’s husband, he hasn’t been a good partner.

Empathising with a character seems to lower our guard, essentially, making us more receptive to learning about ourselves. I think this is what Currie has in mind when he says that narrative can put our values to the test: by immersing yourself in another person’s perspective, you might come to realise you value things that, on reflection, are not worth valuing, or reconsider values you already suspected were wrong. Watching as a character’s relentless pride causes harm to people they love, for example, might invite you to reflect on whether you value pride too highly. Similarly, witnessing a character’s obsession with ‘never giving up’ could reveal a destructive side of perseverance that you hadn’t previously considered.

Certainly, none of these epiphanies would be of much help unless a person who’s recognised something about themselves follows through with actions. We can imagine some of the ways this might unfold. The sudden realisation about pridefulness could make a person more careful about how much they self-promote; reading about obsessive goal-pursuit could lead a person to weigh their priorities more thoughtfully. And seeing the impact of anger (or sarcasm, or other confronting forms of expression) in a new light might encourage a viewer to temper their own in future interactions.

The fact that a TV show helped me see myself more clearly doesn’t mean that all those previous, uncomfortable conversations with my friends and partner about my anger were useless. For as great a show as The Sopranos is, I suspect that watching it can’t have possibly done all the heavy lifting in making me recognise my issues. Had I not had those prior confrontations, I probably wouldn’t have been as quick to grasp the insight about myself. Rather, the lesson to draw from this is that having a wide range of experiences in which imagination and empathy are encouraged can crucially help with developing insights about your character. What watching TV showed me – and what reading a book, watching a movie, or flipping through your favourite magazine might show you – was that our friends do not have to do all the work for us. We can learn from ourselves through narrative, but only if we are willing to engage with it with the candour and bravery of an active mind.