Every time I read that poem, my heart would ache for my father. I knew that I had to have this poem on me so I could carry it with me … The day that [it was tattooed] on my leg, I felt so light and so relieved … I have a little piece of him always with me, no matter how often my heart breaks.

– a woman describing her memorial tattoo

Grief is a complex response to loss that has many dimensions. Contemporary theories of grief acknowledge this complexity and variation, such as in the ongoing relationships or continuing bonds that bereaved people have with deceased loved ones. There is also growing evidence that meaning-making – defined as a process of considering what an event, such as the death of a loved one, could signify or how to interpret it – is an important factor in the experience of grief. Research suggests that a greater sense of meaning after a loss corresponds with less reported distress. Conversely, the risk of experiencing complicated grief, which involves a persistent and pervasive grief response, appears to be higher in the absence of meaning-making. The search for meaning after the death of a loved one is often not an easy or passive endeavour, but an active process that can take many forms.

These perspectives on grief have supported the exploration of a wide range of responses to loss, including a visual form of personal memorialisation that we and other researchers have recently examined: memorial tattoos. One of the key reported motivations for tattooing is the expression of a personal narrative, and memorial tattoos specifically have become a prevalent way for people to remember their loved ones and mark the grief experience in all of its manifestations. Memorial tattoos have many potential functions: they might help to start conversations about a loss; signify changes in one’s identity as a result of loss; provide a permanent representation of love for someone who has died; facilitate adjustment to the loss; and help someone to maintain their bond with the deceased. These tattoos can also challenge the tendency to pathologise grief. As the author of a 2009 paper on grief and tattooing explained:

Tattooing one’s grief can be an act of resistance to the notion that grief can or should be cured … The act of tattooing suggests that grief is permanent and that it is life-long, visible, and always present.

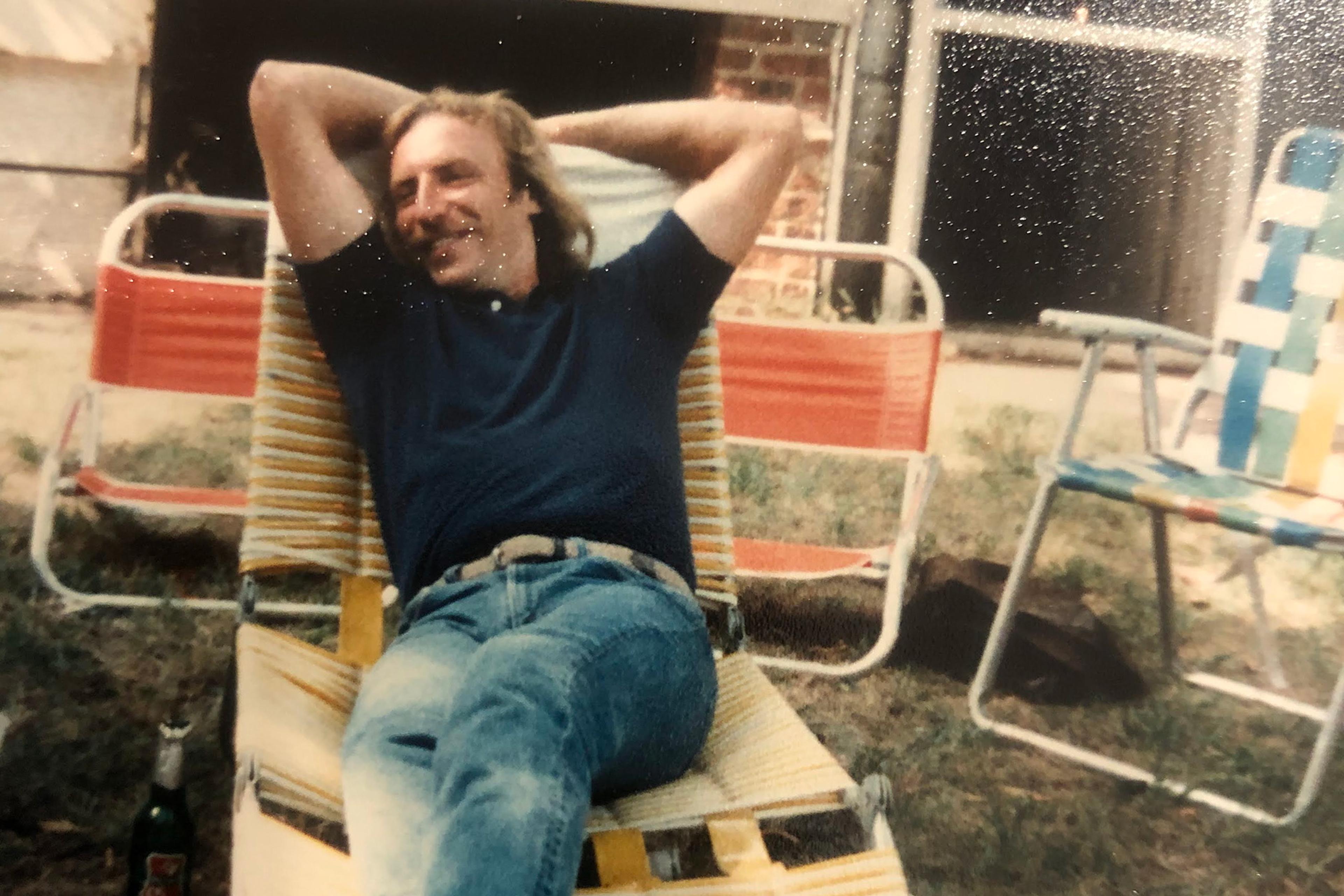

Intrigued by the prevalence of memorial tattoos and what they might show us about the contemporary grief experience, we set out to explore their role as an active response to loss. We interviewed 22 people (21 women and one man) who ranged in age from 18 to 49 years old. These individuals had sought memorial tattoos in response to the deaths of friends, siblings, fathers, a father-in-law, grandparents, a godparent, an uncle, and pets.

When we analysed the interviews, we detected a core theme of what we call embodied meaning-making. These memorial tattoos were visual and tangible expressions of the process by which individuals attempt to make sense of their loss. One participant described her memorial tattoo as ‘an external scar representing an internal scar’. Another shared that her tattoo is ‘a good way to tell a story’ about her loss – a key element in making meaning about a loss. A third related that the memorial tattoos that she and her family members got to remember their deceased loved one ‘were the start of our grief process or the acknowledgement of our grief process’.

Just as there is great variation in the grief experience, there is great variation in memorial tattoos. While some of the participants’ tattoos included traditional memorial symbols such as birth and death dates with initials or names, crosses, and angel wings, many did not. One tattoo was an image from a stamp that was on the last postcard her grandfather had sent her. Another was a heart made out of puzzle pieces. There was a tartan wrapped around a Scottish thistle, a teacup with a chickadee and wild flowers, paw prints, and song lyrics.

For some of the people we spoke to, their tattoo reflected their own experience of grief, the pain of loss, an image or words to express their devastation. For others, the tattoo reflected the deceased family member, friend or pet – their characteristics, favourite activity, items they loved, or their name (sometimes in the form of a signature). Still others designed their tattoo to be an amalgamation of the characteristics of their loved one and themselves, whether in the form of an inside joke, a shared experience, or a shared trait. As one participant said of her tattoo memorialising a loved one: ‘It’s like I’m a part of her. She’s a part of me. That’s our link.’ The various ways in which these tattoos represented people’s loss, their grief and their deceased were powerful embodied symbols of their meaning-making process in adapting to loss.

Many of these bereaved individuals talked about their memorial tattoo as an expression of their need for a sense of permanence in response to painfully clear impermanence – a reaffirmation of life amid the stark reality of death. As one participant eloquently put it: ‘A tattoo is for life.’ Others expanded on the same theme, albeit with some acknowledgement of their own mortality. ‘This is forever,’ one person said. ‘You know, I mean as long as I’m around, this will be around … this is my way of keeping him alive.’ Another participant observed: ‘There doesn’t seem to be a lot of memorials that are as permanent. If you move away or you go somewhere, the memorial doesn’t go with you, but a tattoo does.’

The ever-present tattoo represents the ever-present connection a person has with their deceased loved one. The memorial is on the body, part of the body. No other kind of memorial is as intimate or as embedded in the personhood of the individual.

Another affordance of memorial tattoos is a measure of control in response to an uncontrollable situation. In getting a memorial tattoo, the bereaved people we spoke to exerted control in their choice of the image, where to place it on their body – most often, it was on an arm, a shoulder or a leg – and the degree to which they shared it with others. ‘It’s nice to have that one bit of say about something,’ one participant told us, ‘especially something as important as this.’ Another explained that her grandfather died after a lengthy illness that ravaged his body. She exerted control in her choice of memorial tattoo – a portrait of him in good health. She explained:

Every time I’d remember [him], I’d just picture him when he was sick. It’s like I couldn’t remember him when he was healthy. So, I resolved to get something very permanent in tribute to him … something from much more happy times, something much better to remember him by … I was so happy when it was done, it was almost like it was popping out of my arm, like, seeing [him] again. A feeling of pride and joy almost overcame me.

The choice of where to locate one’s tattoo can even be an act of control in the sense that it allows someone to share their story of loss, or not, depending on how they feel. As one interviewee with a concealable tattoo said: ‘I can go my whole life knowing people and they probably wouldn’t even know that I had [a memorial tattoo]. That’s kind of cool. I can decide who gets to see it.’

For some, memorial tattoos provide a means for maintaining a sense of connection with a deceased loved one. They represent and facilitate a continuing bond – a bond that was changed by death but nonetheless endures. ‘It’s almost like having him close,’ one woman told us of her grandfather. ‘I’m just always holding that part of my arm … and he’s that much closer to me.’ ‘I wanted this reminder to carry with me,’ another person said, ‘because for some reason just holding it in my head wasn’t enough …’

In these various ways, memorial tattoos offer a visual entryway into the individualised grief experience. They reveal some of the strategies by which people facilitate their adaptation to loss. Indeed, memorial tattoos could be the mark of an active and adaptive meaning-making process – one that has the potential to be protective against the complications that can arise in the absence of such meaning.