Warning: this film features rapidly flashing images that can be distressing to photosensitive viewers.

If you were handed a pen and asked to draw a person, where would you begin? You might start with an oval for a head, adding small half-circles on each side to depict ears. Or perhaps you’d draw an eye in the shape of an almond, fill it with an iris, pair it with another eye of the same size, and decorate them with some bushy eyebrows before continuing on with the rest of the face. If you’ve studied illustration, you might sketch out a body using lightly drawn circles and lines. Or, you could draw a person the way a bird chirps.

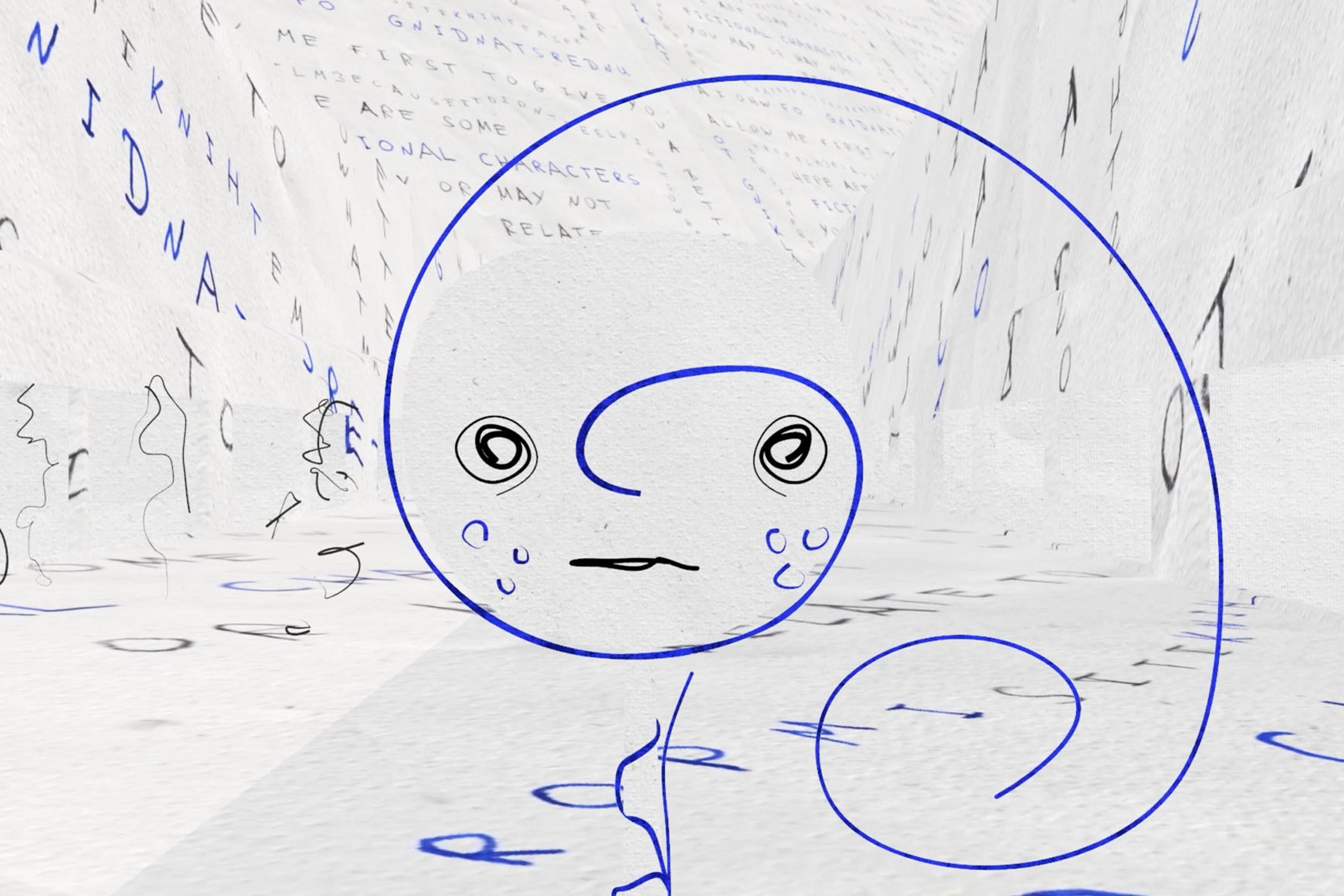

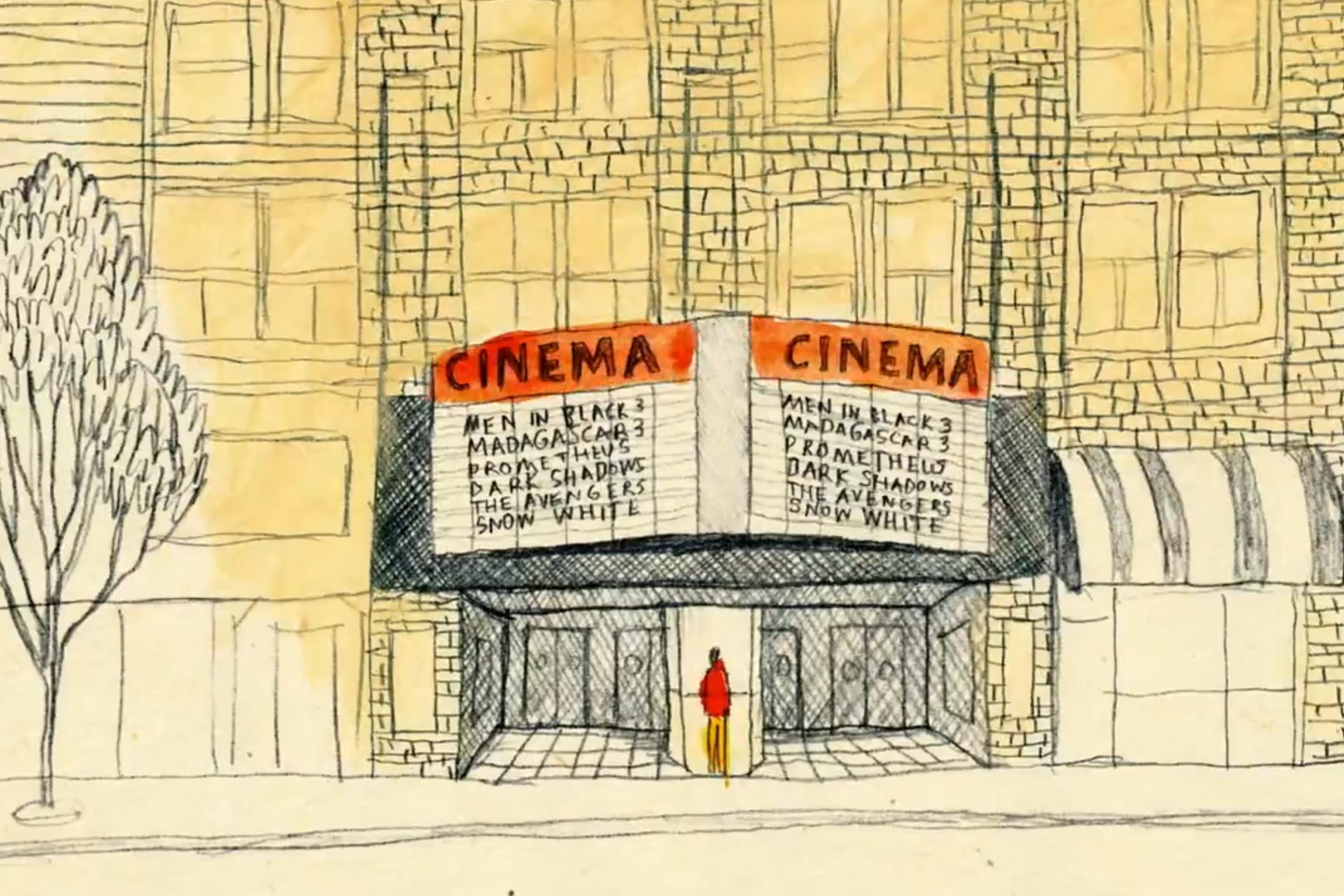

This unusual last option is part of the lesson plan laid out by the Russian animator Sasha Svirsky in 9 Ways to Draw a Person (2017). As its title suggests, the film is an exercise in the many ways that people can be depicted. But instead of simply reiterating the basic principles of animation developed over the past century by masters such as Walt Disney and Hayao Miyazaki, Svirsky creates his own language in the form of abstraction. By untethering himself from the conventions of drawing, he is able to play freely, culminating in a frenetic display of artistic liberation.

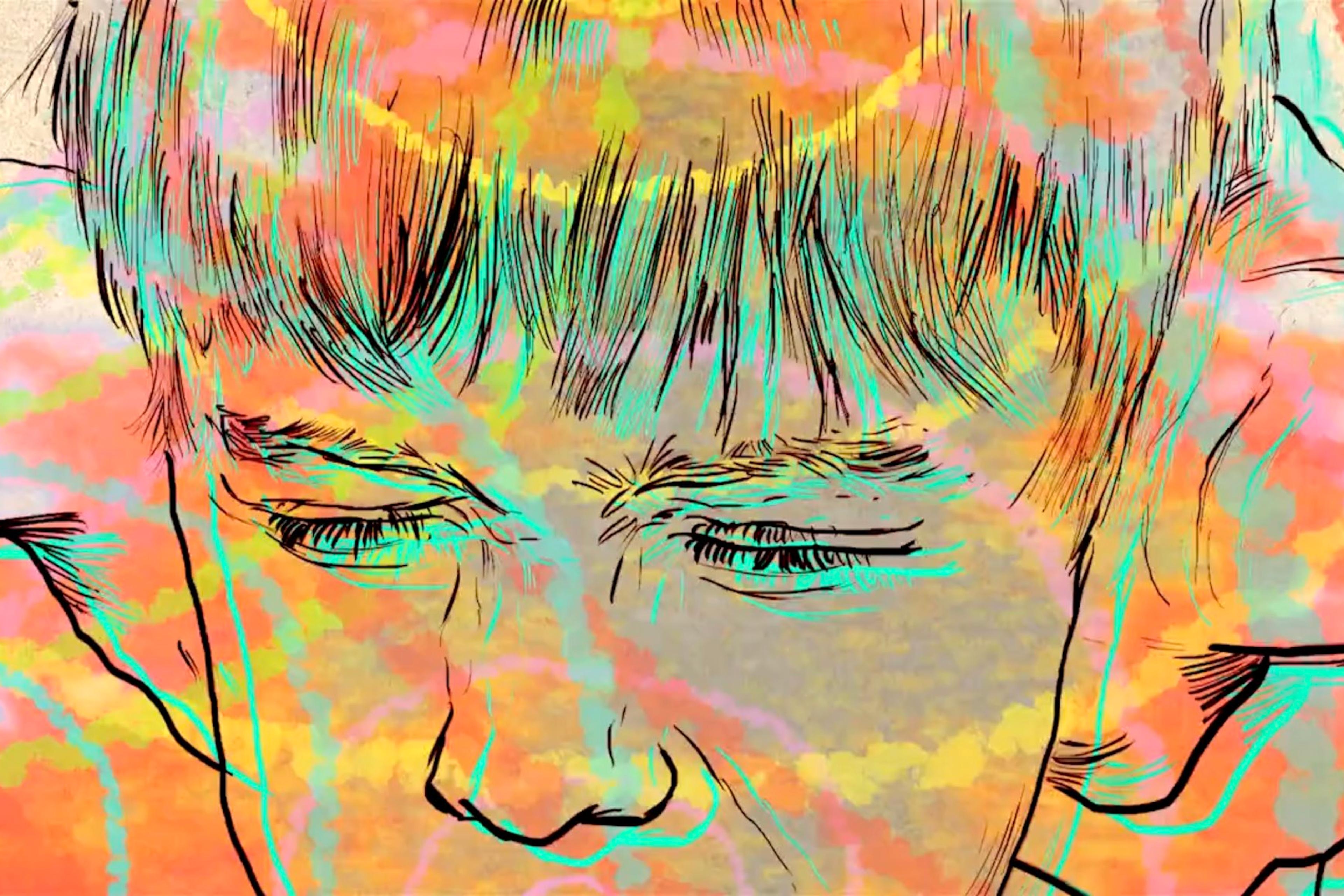

After studying traditional Russian realism at the Grekov Art College in Rostov-on-Don, Russia, Svirsky decided to abandon his formal training and teach himself animation. Since 2008, he’s created numerous acclaimed animated shorts, all the while refining an unusual practice based in improvisation. The outcome of this approach can be seen in each of the nine lessons, as figures morph and dissolve at an exciting pace, as if an artist’s sketchbook has been summoned to life. The controlled visual chaos is amplified by the accompanying rhythmic soundtrack from the Russian composer Alexey Prosvirnin.

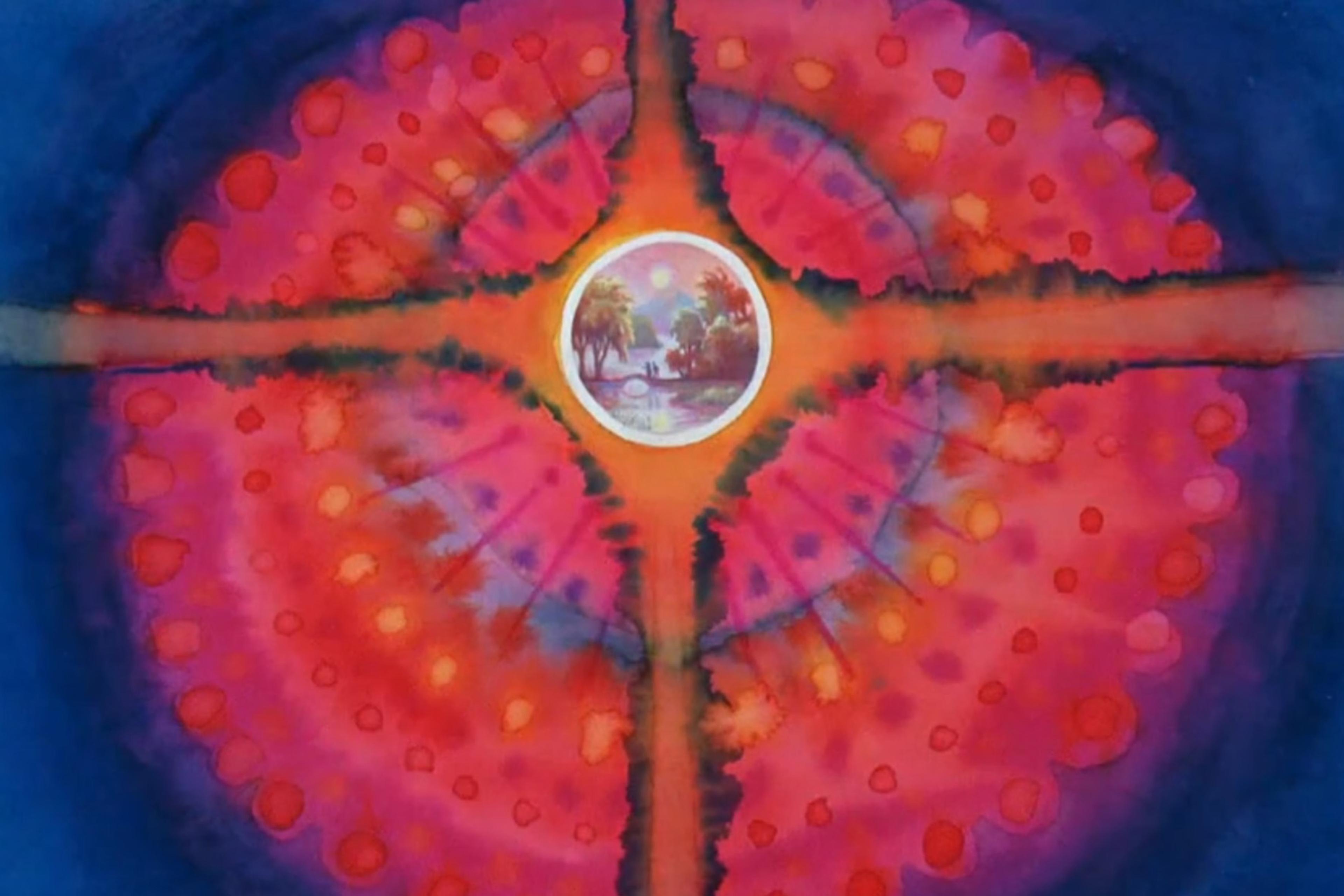

As a self-taught animator, Svirsky’s style is distinctively that of a rule breaker, yet it’s also seemingly fed by a deep knowledge of art history. His imagery recalls the photomontages of the German artist Hannah Höch, as well as the chaotic ink work of the British illustrator Ralph Steadman, while still remaining fresh and original. Indeed, the most notable of his influences are the European artists of the Dada movement, of which Höch was a part, who embraced absurdity over realism in reaction to the atrocities of the First World War. Just as the Dadaists used parody to poke fun at religion, culture and society as a way to better understand the messiness of human nature, so too does Svirsky find inspiration in detachment.

The film is filled with countless small surprises. Each new frame holds the beginning and end of its own artistic thought process, the sum of which add up to an unpredictable dance of eclectic imagery. Svirsky diverges from traditional animation norms in fun and unforeseeable ways by improvising within a medium that usually demands extensive planning, and, by doing so, proves that one can chart one’s own creative path.

Written by Tamur Qutab