In an all-but-abandoned mountain town built of stone, a bearded man alternates between daily tasks and pensive reflection. He sits in a church. He eats a meal. He visits a grave in a small cemetery. He stares off into the foggy distance. He does all of this alone. The soundscape is dominated by small noises – raindrops, chirping birds, the crackling of leaves and dirt beneath his feet – that, in almost any other town, would be drowned out by voices in conversation and society in motion. The only hint of another human presence is the distant rips of a chainsaw, which, in time, is revealed to be two people cutting down trees for lumber. From his heavy eyes, creased face and solemn expression, it seems that the man carries a burden, but, for most of this short film’s duration, it’s unclear what this is.

Watching Clouds Over Corippo (2019) feels something like seeing a series of Romantic landscape paintings brought to haunting life. And, like experiencing a still artwork absent a full narrative arc, the world within it can only be gleaned from small details and outside context. From the film’s title, it’s clear that the trapped-in-time town is Corippo, Switzerland – a historically Italian-speaking municipality on the Swiss-Italian Alpine border, with a population that’s dwindled to the edge of single digits. From the credits, we see that the man’s name is Lorenzo Schifferli. From a final sequence featuring a series of old family photos, we learn that he seems to have suffered an immense tragedy that’s defined his life ever since.

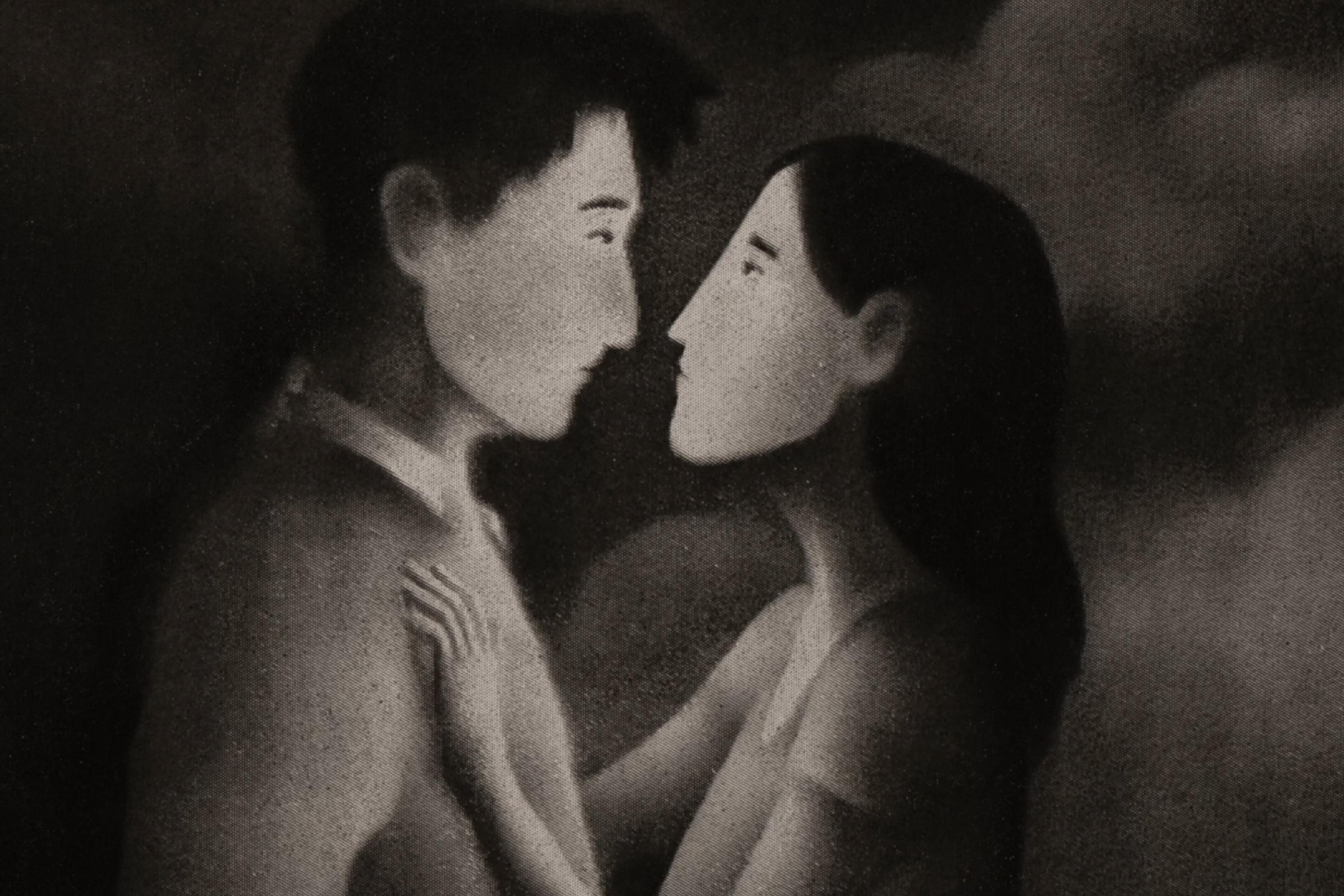

The Armenian-American filmmaker Hayk Matevosyan directed Clouds Over Corippo under the tutelage of the Hungarian filmmaker Béla Tarr, known for quotidian portraits shot in an observational style. After a chance meeting with Schifferli at a café, Matevosyan composed what he calls a ‘hybrid short documentary’ of his life from scenes around Corippo, blurring the line between fiction and reality. Indeed, it’s never quite clear whether it’s Schifferli the man or Schifferli the character who, per the filmmaker’s description, has outlived his wife and children. Through this framing, the film again elicits the more subjective storytelling of a still artwork, with emotions driven by composition and mood, rather than that of a traditional film narrative in which emotions are drawn largely from the plot. Indeed, during filming, Tarr would show Matevosyan the paintings of the German Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich, known for his landscapes depicting human smallness set against the mighty, austere natural world.

With its elegant cinematography, built around uninterrupted shots of the kind of humble life that mainstream filmmaking so often ignores, Tarr’s influence is deeply felt throughout the film. So is that of Friedrich, with his Gothic scenes of man set against the imposing grandeur of the world around him. Yet, drawing from these sources of inspiration, Matevosyan crafts a powerful portrait in a distinct voice that, despite its measured pace, sombre tone and many ambiguities, remains captivating throughout. While the story itself is opaque, the themes it captures – grief, loneliness and the persistence of memory – shine through and are deepened by the film’s many small mysteries.

Written by Adam D’Arpino