‘I remember these cicadas had overrun our backyard. We had all these bugs in our drawers, in our walls.’ So begins the narration of the short film All These Creatures by the Australian director Charles Williams.

Tempest, our narrator, is an adolescent trying to make connections between his father Mal’s erratic, frightening behaviour and the infestation that plagues their home. The cicadas appear shortly before Mal is ‘sent away’ for the first time, so Tempest can’t help but hold on to his father’s idea that the insects are a curse or a warning.

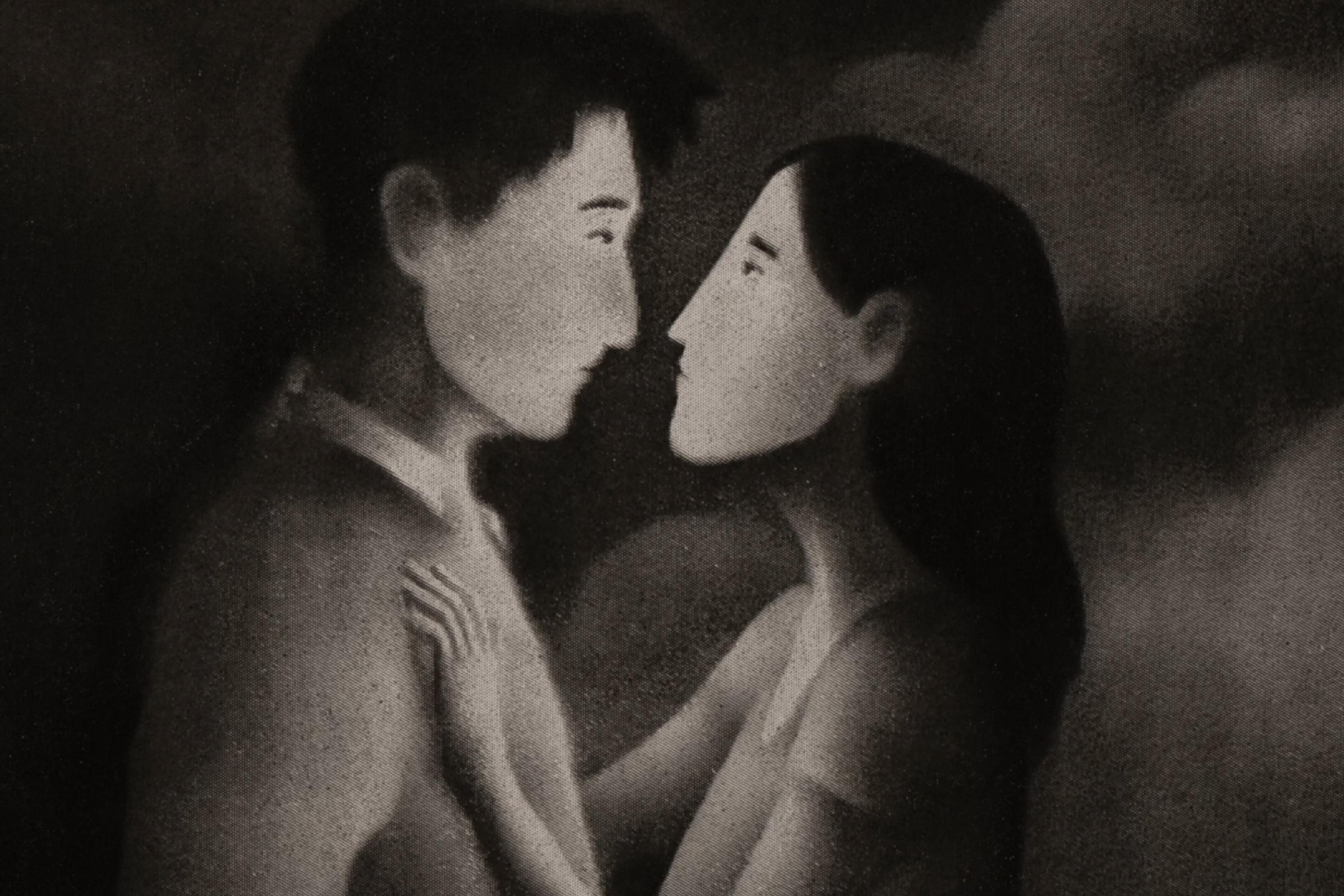

The film, which has won numerous awards, including the prestigious Short Film Palme d’Or at Cannes in 2018, immerses us in Tempest’s world in a curious way – a fluid interweaving of the past and the present. Everything that he recounts is a memory of something that has already happened, but the depictions of those memories, though often dreamlike, have the immediacy of something unfolding before us. Sometimes the narration recedes, grounding us even more strongly in the present. This relationship between Tempest’s words and the images we see bring us into his psychic space, offering access to his lived experience, in the moment, alongside a more reflective, meaning-seeking mode.

In an interview about the impetus for this film, Williams described how he ‘was thinking about how we all reckon with the images we have of our parents over time, and how we eventually come to see them as people instead of these mythic figures in our heads’. Tempest’s narration is indeed grappling with a youthful form of this reckoning, of trying to understand his father. Although he hears the different theories people put forth about Mal’s troubles – that he’s possessed, that he needs to get right with God, that there’s something wrong with his brain – Tempest doesn’t think anyone really knows. He senses that his father might have some special knowledge.

While the narration traces a boy’s attempts to make sense of his father, the present-tense aspect of the story points to the trauma of abuse, neglect and fear. As a reflection on the effect that a parent’s mental illness can have on a child, the film is poignant, especially as Tempest returns several times to the worry that whatever got into his father might get into him. Even more troubling is the father’s final act, which we don’t see but Tempest tells us about.

In an Aeon essay, Jesse Bering writes:

Given the tendency for traumatised human beings to fall prey to their own self-fulfilling prophecies, experts say that it’s vital to unpack readymade explanations of genetic susceptibility with more nuanced language so that older children and teens aren’t left to their own fatalistic reasoning … The hereditability of mental illness isn’t so straightforward.

But while Tempest might be precariously close to repeating a received narrative about his own susceptibility to mental illness, he’s also doing something else – he’s trying to redeem his father through his own storytelling and imagination. In making a film about a boy poised on the razor’s edge between healing and perpetuating harm, Williams wisely eschews resolution, leaving Tempest to forge his own future. It’s a sensitivity that imbues the whole film, from the choice to work with Ethiopian community advisors after casting the Ethiopian-Australian actor Yared Scott as Tempest, to the decision to avoid direct depictions of violence. These choices undergird Williams’s cinematic talents with substance, and give credence to the possibility that the cicadas might indeed carry a deeper significance: not only have the insects long symbolised rebirth and transformation, but in Phaedrus Plato connects them with madness and divine inspiration. In contending what he knows about his father, Tempest seems to sense this terrifying, enlivening possibility.

Written by Kellen Quinn