Zoos are, without a doubt, deeply complicated institutions, as much for their compromised history and contested, evolving purposes as for their ontology. In his much-cited essay ‘Why Look at Animals?’ from the anthology About Looking (1980), the British critic and writer John Berger wrote:

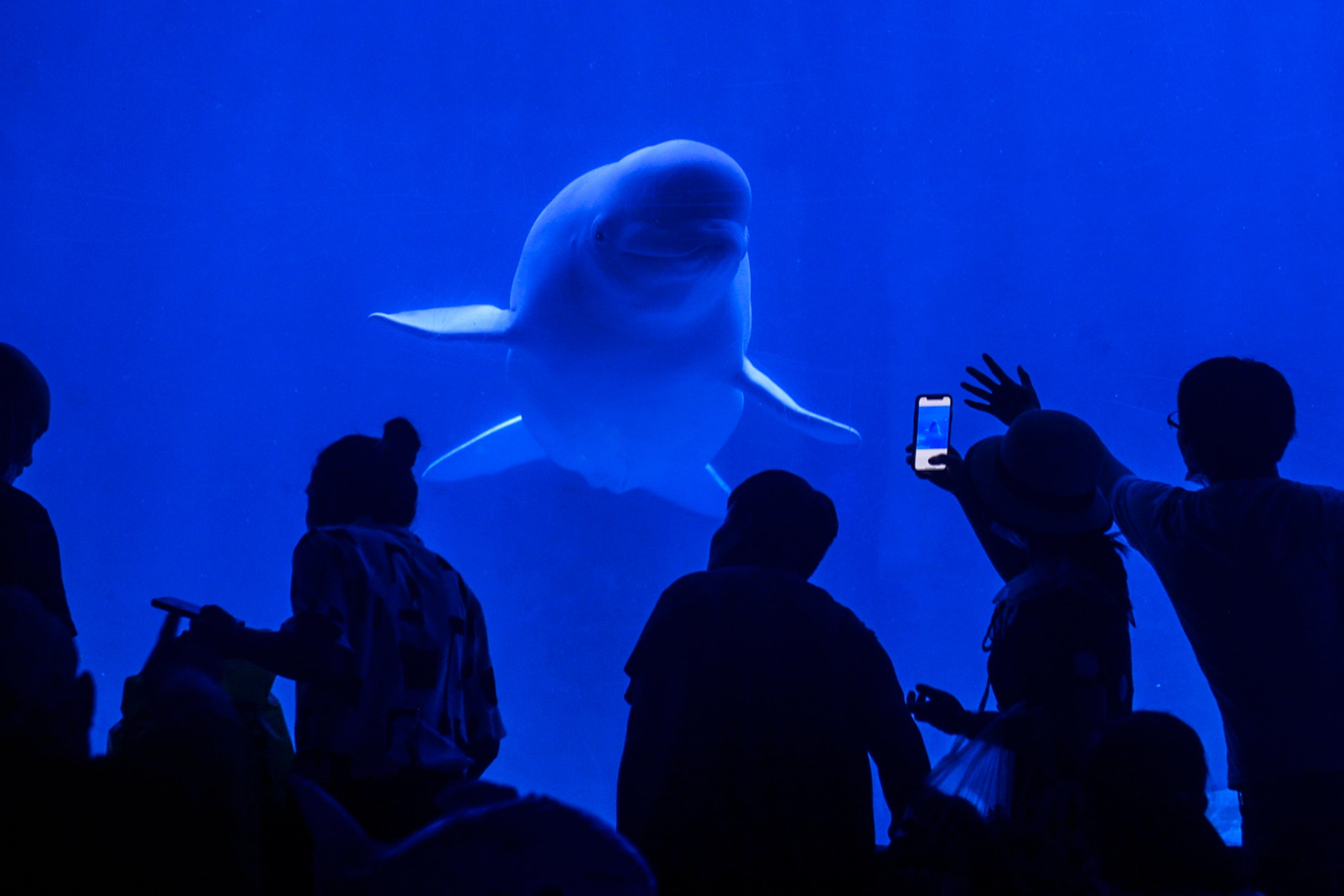

Public zoos came into existence at the beginning of the period which was to see the disappearance of animals from daily life. The zoo to which people go to meet animals, to observe them, to see them, is, in fact, a monument to the impossibility of such encounters. Modern zoos are an epitaph to a relationship which was as old as man …

The zoo cannot but disappoint. The public purpose of zoos is to offer visitors the opportunity of looking at animals. Yet nowhere in a zoo can a stranger encounter the look of an animal. At the most, the animal’s gaze flickers and passes on. They look sideways. They look blindly beyond. They scan mechanically. They have been immunised to encounter, because nothing can any more occupy a central place in their attention.

Therein lies the ultimate consequence of their marginalisation. That look between animal and man, which may have played a crucial role in the development of human society, and with which, in any case, all men had always lived until less than a century ago, has been extinguished. Looking at each animal, the unaccompanied zoo visitor is alone.

If this searing assessment of what the zoo is and what it means feels compelling, but dispiritingly grim, the short documentary Zoo (1962) can bring back the fun, without discrediting Berger’s acute analysis. The film, by the Dutch filmmaker Bert Haanstra, came out nearly two decades before the essay, so it’s not so much a response to Berger’s ideas as a peculiar variation on the theme of the zoo and what it is for us to look at animals. As in his brilliant short Glas (1958), Haanstra’s filmmaking shows a warm, expansive curiosity for human endeavours. With a jazz score that’s by turns cheerful, cheeky and acerbic, winding round and through cleverly constructed sequences that draw out similarities, contrasts and parallels between animals and people, Haanstra constantly has us reassessing who’s watching whom. With its comical juxtapositions and delightful absurdity, the whole thing is playful, funny and gleefully anthropomorphic.

At the same time, beyond the marvelling at – and good-natured mocking of – behaviour that bubbles along throughout the film, there’s a sharper edge to Zoo. At times, Haanstra seems to overcome the separation that Berger describes, creating connections between people and animals through editing that has the effect of making us forget the bars and cages. But, just as often, we see those barriers plain and clear, sometimes from perspectives that put the humans behind them. And a simmering weirdness occasionally boils over into sharp discomfort, though without missing a jazzy beat, such as when a tiger seems to lunge at an onlooker or gawking faces appear to be unsettling the animals in an enclosure.

Like Berger, Haanstra is an extraordinary observer and his manipulation of ways of seeing imbues the experience of the zoo with the fascination that draws us there in the first place and with a simultaneous uneasiness that seems to prefigure Berger’s contention that:

With their parallel lives, animals offer man a companionship which is different from any offered by human exchange. Different because it is a companionship offered to the loneliness of man as a species.

Perhaps the shy – or horrified? – little monkey at the end of the film says it all.

Written by Kellen Quinn