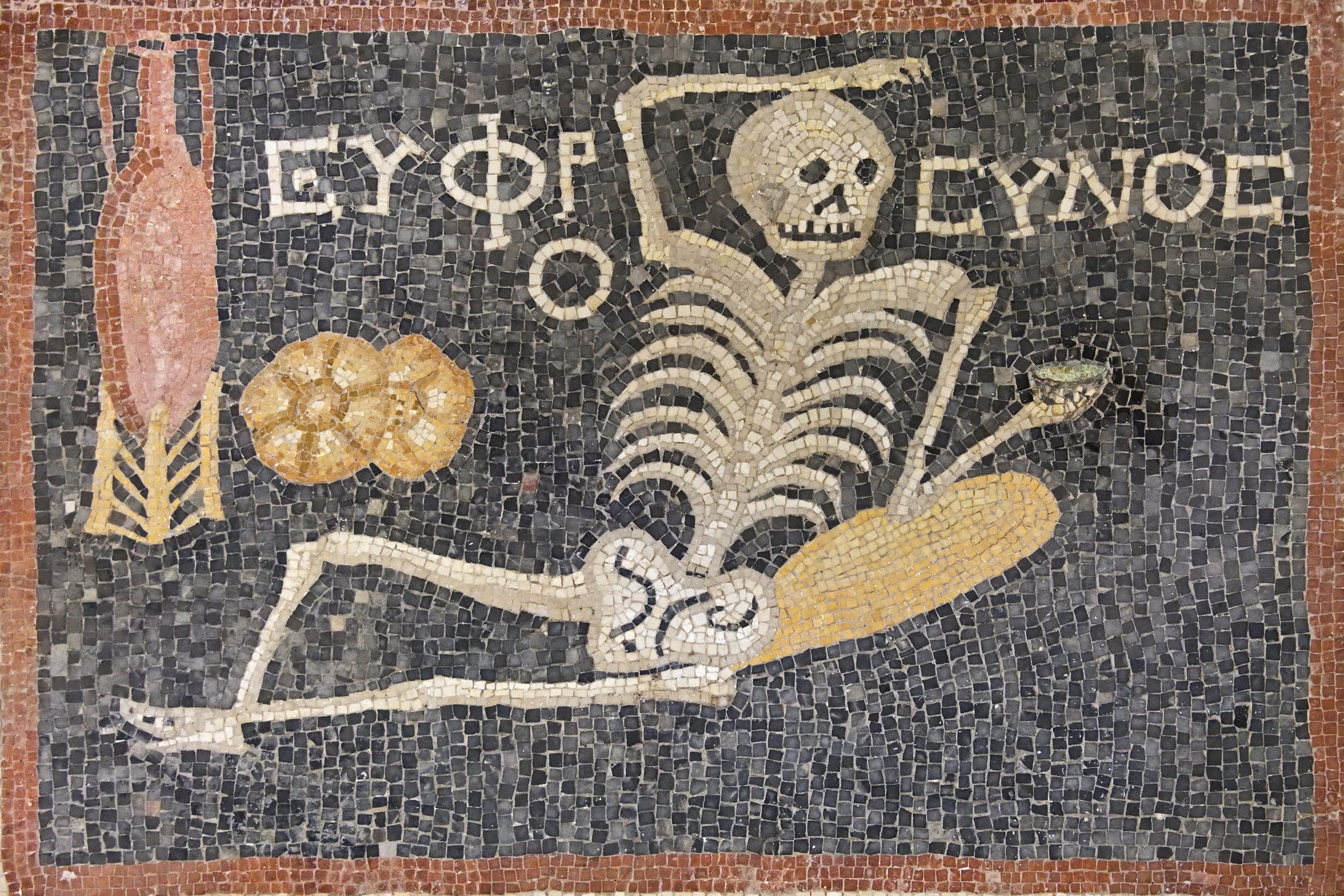

One way or another, we will all approach the end of life, we are all terminal, and existential anxiety can be a burden long before this. Studies by terror management theory researchers have found that when death salience is aroused in people, they adapt their behaviour and increase their reliance on defence mechanisms such as denial. The cultural anthropologist Ernest Becker argued in The Denial of Death (1973) that human civilisation is ultimately a symbolic defence mechanism against the awareness of our finite existence. He suggested that ‘consciousness of death is the primary repression, not sexuality’ as Sigmund Freud had popularised. Unconscious denial of death can have a demoralising effect on an individual, potentially affecting loved ones and the community as a whole.

By not facing the issue of our mortality prior to our passing, we miss a unique opportunity, not only to reconcile with death and make peace with it, but also to gain a sense of levity and serenity that we can carry with us through our lives. But how can we overcome a fear of death that’s so deeply rooted in our culture?

Research is starting to reveal that certain states of consciousness can have a powerful and positive effect on how we perceive our own mortality. There’s a strong association between a decreased fear of death and undergoing a near-death experience (NDE), out-of-body experience (OBE), lucid dream and psychedelic experience.

During an NDE, people report several features such as a transcendence of time and space, a life review, feelings that the experience is ineffable and authentic, encounters with deceased loved ones, and deep feelings of love and peace. One of the core transformative features of the NDE is an out-of-body experience, which is also associated with psychedelic experiences but, unlike these other states, is something that can be induced through training and intent.

One doesn’t even need to have these experiences personally to benefit from them. A number of NDE researchers have noted profound changes in their own outlook following encounters with people who have had an NDE. As noted by one leading researcher, simply hearing or reading about NDEs can have a profound impact, acting as a ‘benign virus’. Research has revealed that this can yield significant changes in people’s spirituality and appreciation for both life and death.

The psychiatrist Elaine Drysdale, who works with terminally ill cancer patients in Canada, has heard countless reports of NDEs, and assures patients and their relatives that the experience of death itself isn’t as painful or frightening as it might appear. She now teaches medical students and palliative care staff about the benefits of near-death research, and argues that NDEs allow us to approach the unknown and death without framing things in a religious way – they’re inclusive, personal and occur in cultures all over the world.

An OBE is a transpersonal experience where you feel your ‘sense of self’ shift beyond your physical body, encountering beings and places that feel real. Unlike NDEs, OBEs can be induced willingly. This experience can also occur spontaneously in healthy people while they’re deeply relaxed, in hypnagogic states, on the cusp of sleep, and during meditation. Almost all OBEs have a positive impact, with experiencers commonly reporting a sense of serenity, mental clarity, awe and interconnectedness.

The experience can act as a motivating catalyst to further understand yourself, and is commonly associated with a reduced fear of death. As the American neuroscientist Sam Harris points out: ‘whether or not a person’s consciousness can actually be displaced is perhaps irrelevant; the point is it can seem to be.’ Distortion of embodiment can be disorientating, but disorientating to whom, if we experience that we aren’t solely the totality of our body? One core feature linking these various experiences is the feeling of transcending one’s primary identification with the physical body. The perspective-shifting power of this effect is supported by experiments showing that even a simulated OBE induced by immersive virtual reality can lessen death anxiety.

The experience of transcending the physical body is frequently tied to feelings of connecting to something larger than oneself. This is usually associated with the experience of awe, an emotional state commonly linked to NDEs, OBEs and psychedelic experiences. It’s also experienced by astronauts when viewing the Earth from space, referred to as the ‘overview effect’. It conjures a cognitive shift of perceptual vastness, reframing one’s reality and place within it. This draws parallels with OBEs and NDEs, which appear to evoke a kind of ‘outerview effect’ when people glance back at their body and feel separate from it. This change of core identification from a limited body to a more expansive sense of self can radically curb existential anxiety.

These altered traits could be related to ego-dissolution, which is another important experiential component of transcendent experiences. Such experiences are reliably catalysed by psychedelics and characterised by a loss of subjective self-identity; in essence, a simulated dying or death and rebirth experience. Following its dissolution, there’s a blurring of the perceived boundaries between self and other. Deep feelings of unity, awe and interconnection can stem from this. This experience is strongly associated with the mystical-type experiences that psychedelics can elicit and appears to be an important part of how psychedelics can alleviate death anxiety. Psychedelic therapy might also invoke a sense of ritual – something that has largely been lost to Western culture, but is an important part of many Indigenous cultures, including those that employ psychedelic substances, such as psilocybin, shamanically.

The evidence of the efficacy for psilocybin in treating existential angst is arguably the strongest of any yet obtained in the field of psychedelic research, following clinical studies conducted by the University of California, Los Angeles, Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore and New York University (NYU) exploring psilocybin as a treatment for existential anxiety in terminally ill cancer patients. Follow-up research by NYU found sustained reductions in death anxiety 4.5 years after a single psilocybin session in the overwhelming majority of study participants. Psilocybin can also catalyse feelings of death transcendence in those who aren’t facing a terminal diagnosis. This is an unprecedented finding in the field of psychiatry.

In the words of Anthony P Bossis, a clinical assistant professor of psychiatry at the NYU School of Medicine and the former director of palliative care research for the NYU trial:

While there have been advances in chemotherapies and pain management, there remains a paucity of therapies to address and relieve the emotional anguish experienced by the dying. The psychedelic therapy model represents a potential paradigm shift for the future of hospice and palliative care, providing a novel and effective therapy to relieve the emotional and spiritual distress so often experienced at the end of life. Not only can it offer emotional and spiritual healing for those facing their mortality, but it can also help their families who witness the relief of suffering in their loved one.

Another substance that reliably yields ego-dissolving transcendental experiences and might hold promise is ketamine. Numerous studies have found that the experiences it elicits are closest to the NDE, in phenomenological quality, of all substances examined. On the matter of authenticity of psychedelic insights, the veteran American psychedelic pharmacologist David Nichols had this to say: ‘If it gives them peace, if it helps them to die peacefully with their friends and family at their side, I don’t care if it’s real or an illusion.’

The psychiatrist Stanislav Grof has likely supervised more psychedelic therapy sessions than anyone else alive. He treated terminally ill cancer patients with psychedelic therapy as part of his work with the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center. He observed patients describing these sessions as invaluable experiential training for dying, with some reporting NDEs as their disease progressed, which they described as yielding very similar states of consciousness. Grof commented that:

‘dying before dying’ influences deeply the quality of life and the basic strategy of existence. It reduces irrational drives … and increases the ability to live in the present and to enjoy simple life activities. Another important consequence … is a radical opening to spirituality of a universal and non-denominational type.

One thing reported in association with NDEs, OBEs, lucid dreams (dreams in which the dreamer is aware that they’re dreaming) and psychedelics (such as ayahuasca) is encountering deceased loved ones. Whether or not one takes the view such experiences are illusionary or ‘real’ in some sense doesn’t take away from the therapeutic power of these encounters. The Holocaust survivor, financier and philanthropist George Sarlo had a life-changing encounter with ayahuasca in his 70s, during which he had a conversation with his dead father who told him why he hadn’t said goodbye before he was deported to a Nazi labour camp. In turn, feelings of depression that Sarlo had harboured for much of his life evaporated. Others report the resolution of relationship conflicts, feelings of relief, and a sense of closure after encountering a deceased relative. However, these extraordinary experiences aren’t new, as Tibetan Buddhists have been wilfully inducing both OBEs and lucid dreams as part of Dream Yoga practice for millennia, for the purpose of exploring the nature of reality and as preparation for death.

These can be powerful experiences, however they do vary in character. In a comparative study looking at lucid dreams and OBEs, Samantha Treasure found that encounters with figures in OBEs were felt to be more impactful and cathartic than in lucid dreams. While encounters with figures in lucid dreams were generally interpreted as a product of the dreamer’s own mind, figures in OBEs were perceived as more ‘life-like’ and autonomous. It’s this aspect of OBEs, in which the experiencer feels connected to something beyond the self, that appears to make them such an effective salve for existential dread.

These different experiences have their own benefits and drawbacks. While NDEs can be powerfully transformative, they have the distinct disadvantage of occurring when one is approaching death, or at least thinks one is, which incurs far too much risk to the individual. Psychedelics used in a supportive, therapeutic context certainly hold promise, however they require careful handling given their powerful effects, while also being illegal in much of the world. While roughly one in 10 people will experience a spontaneous OBE once in their life, only a minority will experience them numerous times. Like lucid dreaming, however, OBEs are something that can be induced with intent, and through practice. Given their profound psychological effect, OBEs might be the ideal treatment for death anxiety in the underfunded palliative care system.

Jon Underwood, the founder of the Death Café movement, inspired many to talk openly about death. He died suddenly of undiagnosed acute promyelocytic leukaemia at the age of 44 in June 2017. He said: ‘Time is different when you know you’re dying. Time matters. Minutes matter. Time is not to be wasted. Sometime – soon – there will be no more time.’

Perhaps by embracing our impermanence through the use of altered states, we can also help to relieve the collective anaesthetic of death-denial. In doing so, we might empower ourselves and others to meet our shared mortality with peace and equanimity, awaken to our aliveness, and greet death like an old friend.