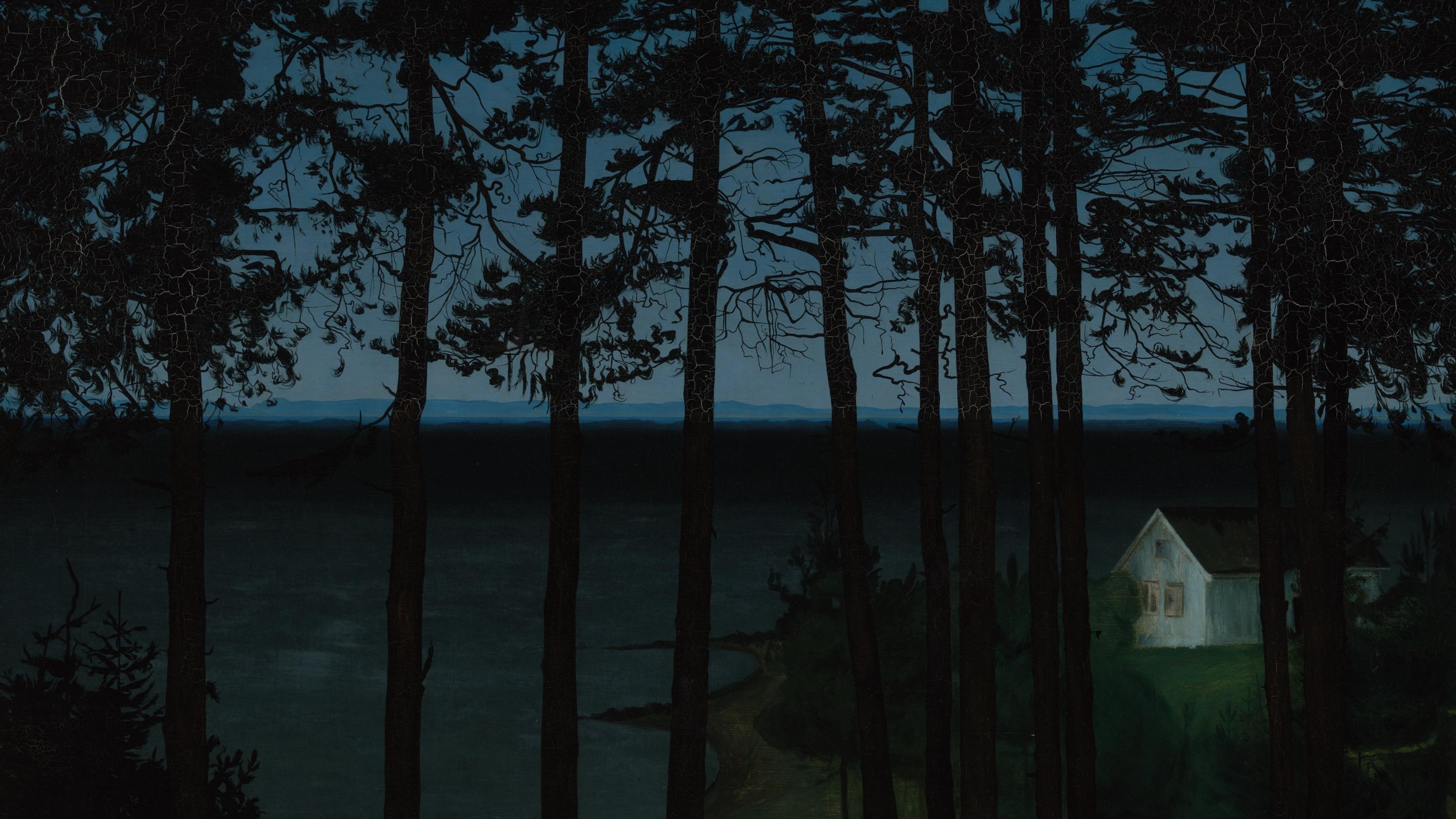

In 1913, a stranger arrived in a remote Norwegian village. He built a tiny wooden house on a cliff overlooking the serene Lake Eidsvatnet and immersed himself in contemplation. The Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, largely a fruit of isolation in Skjolden, was finalised in Italian captivity during the First World War and published in 1921. Ascetic in style, content and composition, the Tractatus marked the beginning of a new era in Western philosophy, establishing its author, Ludwig Wittgenstein, as one of the key thinkers of the 20th century.

An ascetic mindset has been shared by many influential philosophers, scientists and artists. While not all of them were hermits, many tended to embrace a simple, almost monastic existence. Marie Skłodowska-Curie and Albert Einstein were immune to luxury and spent the money from their Nobel prizes on sustaining their scientific or humanitarian projects. Michelangelo received generous payments from Pope Julius II and the Medici but lived like a pauper, often sleeping in his clothes and boots, and eating simple food. Simone Weil, too, embraced ascetic ideals in thought and practice. Her life was marked by deliberate solitude and a commitment to living in solidarity with the oppressed.

In scholarly literature, asceticism is traditionally examined either as a specific religious practice of self-restraint aimed at attaining spiritual perfection, or as a broader cultural phenomenon – any act of self-limitation performed for the achievement of ethical, political or social goals. Many scholars who focus on the second perspective argue that humans possess a certain predisposition towards asceticism, which is viewed as a universal phenomenon and fundamental element of any culture. For example, in The Ascetic Imperative in Culture and Criticism (1987), the literary scholar Geoffrey Galt Harpham compared asceticism to the ‘MS-DOS of cultures’, or an operating system on which specific cultural expressions are based. Following Sigmund Freud, Harpham argued that the inbuilt capability of individuals to limit desires and instincts is a driving force of cultural production.

This perspective aligns with Max Weber’s (now controversial) thesis that inner-worldly asceticism shaped the modern capitalist world. Stepping out of the monasteries in the 16th century, the Christian virtues of frugality, self-discipline and hard work permeated the minds of laymen, and so grounded the economic order we live in today. Not only did Protestant asceticism not contradict economic and cultural flourishing, it contributed to the accumulation of wealth and the acceleration of modernisation in Europe. As capitalist countries have reached unprecedented material abundance and technological advancement – albeit unevenly distributed – I wonder what place remains for asceticism in the modern world and whether we could benefit from reorientating our thinking and living towards ascetic virtues.

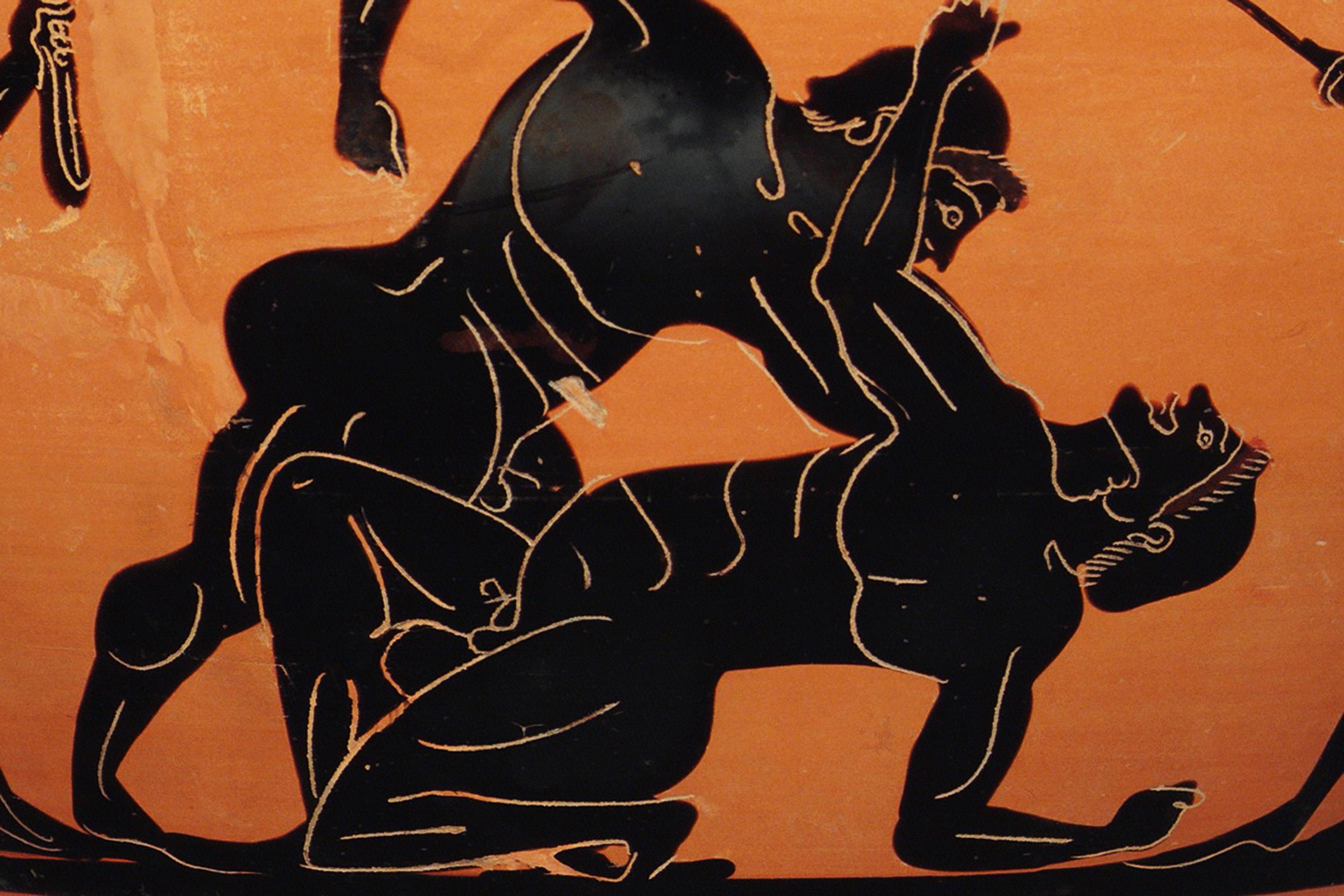

The Greek word ἄσκησις originally referred to ‘exercise’, or a physical training in a gymnasium. Yet, askesis for Greeks was more than merely a physical training. It was also, as the French philosopher Pierre Hadot suggested, a ‘spiritual exercise’, a disciplined practice to master how to live a better life. This broader vision of asceticism is present in Plato’s dialogues and culminates in Roman Stoicism. In the Christian era, athletes and pagan ascetics were replaced by martyrs and hermits, who believed rigorous self-restraint and the mortification of the flesh would lead their souls to salvation.

In the public imagination, however, asceticism is most commonly associated with hermeticism and religious mysticism. Ascetics are seen as zealots who live in poverty and practise celibacy, who torture and starve themselves – all for the sake of self-perfection and approximation to the Divine. Such a lifestyle, extreme and rather exotic for modern consumer society, provokes acute reactions, ranging from admiration to repulsion and even fear. Public prejudice against asceticism is partly due to seeing the ascetic as completely detached from social and political reality. In this perspective, asceticism comes to seem like a ‘luxury’ that might benefit the individual who practises it but has little potential to effect change on a larger scale. But that is not entirely true.

Authentic asceticism is not a blind retreat from reality but an attempt to control it

Asceticism can indeed imply escapism and political apathy, though it doesn’t need to. There are historical precedents for when ascetic virtues were at the core of both individual lifestyles and political ideology. In the Republic, Plato names mastery over bodily desires among the essential qualities of a philosopher and a good citizen. In this respect, Sparta, with its cultivation of self-discipline and individual sacrifice for the common good, becomes Plato’s model for the ideal polis. In the Renaissance, Girolamo Savonarola, a moneyless Dominican friar and de facto ruler of Florence from 1494 to 1498, delivered apocalyptic sermons that both terrified and mesmerised Florentines. Responding to the prophet’s calls, they burnt clothes, jewellery and paintings in the ‘bonfires of the vanities’, hoping to gain salvation in the afterlife. Savonarola’s asceticism became a tool for establishing his political authority over the minds of the Florentine people.

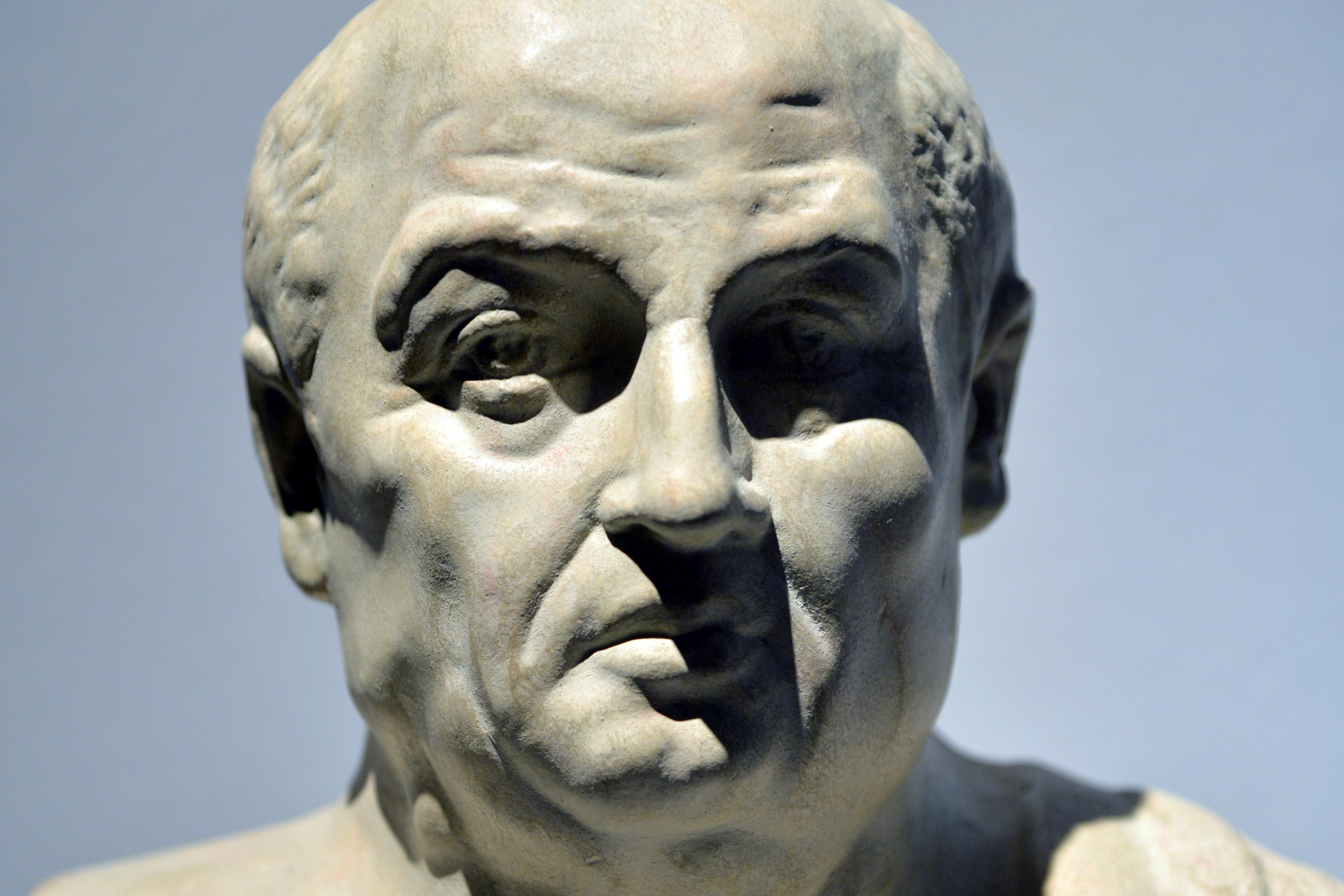

The endpoint of asceticism, whether religious or secular, is always power – power over one’s own or other people’s desires, emotions and thoughts. Authentic asceticism is not a blind retreat from reality but an attempt to control it, just the opposite of how asceticism is often perceived today. Resorting to ascetic practice for self-perfection is thus simultaneously an act of political resistance and social criticism. Socrates’ demonstrative poverty was another way to point at Athenians’ excessive preoccupation with material goods. Savonarola’s disdain for money and comfort was dictated by his inner protest against the luxury that the Catholic clergy so enjoyed.

Ascetics are un-systemic yet valuable agents of change, who silently or explicitly point to society’s ills. The very fact that someone needs to detach from society – physically or mentally, or both – to reach self-perfection implies the impossibility of such a transformation within it. By pointing to society’s weaknesses, ascetics either pave the way for change within their community or end up with the creation of an alternative community built on new principles. This, in turn, means that asceticism, often viewed as an obsolete practice incompatible with late-capitalist modernity, can lead to social innovation.

In the process of secularisation, some ascetic practices have lost their religious content but survived into the modern world. This includes fasting and dieting, social and digital ‘detox’, veganism, low-waste living, slow food and fashion, the cult of fitness, minimalist interior design, and so forth. Modern-day ascetics pursue a variety of goals, ranging from environmental improvement to attaining peace of mind or shaping a body that would better fit the existing beauty standards. The popularity of asceticism in modern consumer societies suggests that finding meaning within them requires limiting their destructive influence. In response to this existential demand, countless books promise guidance on how to think and live simply and mindfully – but the demand only continues to grow, while the social structures enforcing consumerism and environmental deterioration largely remain unchanged. Does that mean modern asceticism has lost its transformative potential?

To answer this question, I suggest approaching asceticism as a ‘technology of the self’, which is a concept explored in Michel Foucault’s later work. ‘Technologies of the self’ refer to practices through which individuals act upon their bodies, thoughts or behaviours to shape themselves in accordance with certain ideals. Foucault viewed asceticism as a tool that could be used either to conform to the dominant social norms or to resist them. In his analysis of Christian monasticism, Foucault showed how such elements of ascetic practice as confession and obedience produced docile subjects and reinforced church authority. By contrast, in his exploration of Greco-Roman ethics, Foucault described how practices of moderation and philosophical reflection served to cultivate ethical autonomy. Ethical autonomy, in turn, may open a path to a new social order built on alternative values.

I believe that decluttering, fasting or minimalist design can benefit individuals’ physical and mental wellbeing. Yet, since modern ascetic practices have been largely commodified, they often turn into another form of capitalist spirituality and become a part of the system that they initially sought to challenge. Modern ascetics seem to be largely driven by a desire to better fit social expectations, even if this desire often remains unconscious. Such a practice misses the broader existential and social reflection that once made asceticism a powerful technology of transformation. Without this reflection, asceticism risks turning into another short-term coping mechanism – whether for stress relief or bodily self-perfection – that might work on a personal level but does not allow for transcending the imposed capitalist mindset.

The transformation towards a more ascetic lifestyle can happen only without coercion

To reclaim its power, modern asceticism should be reconsidered as an act of social criticism and resistance to power structures, motivated not by pride or competition with others but by a desire to cultivate a more critically engaged personality. To be consciously adopted by many, a moderately ascetic lifestyle for personal and common good should be reframed as a path to human flourishing, and environmental and social solidarity.

The reintegration of positive ascetic virtues – such as living with lesser consumption of goods and information, prioritising quality over quantity – could contribute both to economic sustainability and to mental wellbeing. It could help restore balance between the ‘instinct of consumption’ and the ‘ascetic instinct’, releasing our time and energy for intellectual and artistic production and making our life more meaningful. For instance, embracing a low-waste lifestyle or choosing slow food would have a stronger personal and social transformative effect if accompanied by a daily practice of empathy and care toward others. This would not only benefit the planet but also contribute to a more just and compassionate society. Yet the transformation towards a more ascetic lifestyle can happen only without coercion. Historically, enforced austerity has often failed, making people only more passive and discouraged.

Asceticism will not cure us of all the ills of modernity. Neither is it possible for everyone to live in the woods like Henry David Thoreau. Yet, if grounded in care for the self, for others and for the planet, and if internalised as a resistance to the imposed standards of thinking and living, positive asceticism can regain the potential to serve as a transformative force – not only for individuals but for society as a whole. In an age when economic austerity may again become a reality, it is up to us whether adopting an ascetic mindset will lead us to apolitical retreat, a quiet social revolution, or a new cycle of economic prosperity.