Reputations are strange things. Sometimes they closely track merit and significance. Other times they don’t. An example of the latter is François Fénelon, a thinker and political figure whose name today is almost entirely unknown. He was many things: a philosopher, a political reformer, a priest, a towering figure in late 17th-century French life. For many years, he was best known as the author of the novel Telemachus (1699), which he wrote for a grandchild of the Sun King, Louis XIV. Telemachus sought to teach the future king how to rule lovingly rather than selfishly – that is, just the opposite of the way that Louis XIV ruled.

But Fénelon’s significance isn’t limited to Telemachus. In addition to his bestselling novel and many other writings on politics and ethics (which include a pioneering essay on the education of girls), Fénelon wrote extensively and masterfully on spirituality. Many of these spiritual writings were prompted by the raging religious debate of Fénelon’s day: the so-called Quietist Controversy of 1697-99, which chiefly turned on the proper meaning of ‘pure love’.

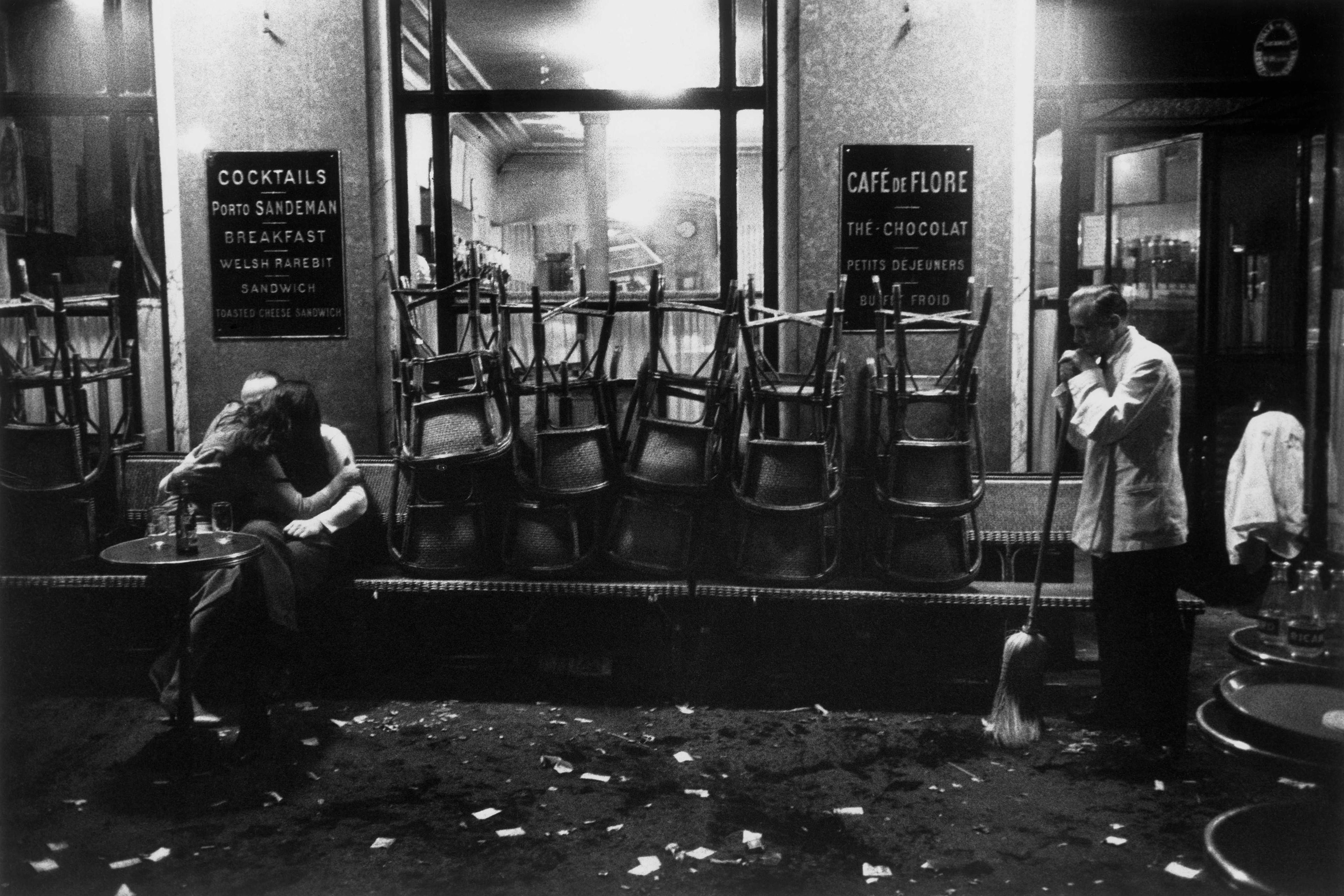

Death came for Fénelon at age 63, in 1715 – the same year it came for the Sun King, with whose life Fénelon’s was inextricably tied. And herein lies his first claim to our attention today. Fénelon spent his political life organising and leading the resistance to Louis XIV. As is immediately evident to every tourist who visits the Palace of Versailles, Louis was a man with unbounded love for himself. Versailles remains a monument to his immense vanity and self-obsession, and his approach to political rule was determined by the same love of grandeur and glory that led him to build his palace. Scholars today often use the term ‘absolutist’ to describe this approach, in which the king, ruling in the belief that he governs by divine right, does all he can to ensure he always stands at the centre of all things. The approach is captured well by the most famous (albeit likely apocryphal) line associated with Louis: L’état, c’est moi – ‘I am the State.’

With all of this Fénelon had little truck. Louis’s penchant for personal greatness and glory led him, in Fénelon’s view, to place his own interests above those of the French people. The king waged a series of pointless foreign wars in order to gratify his ego, which served only to ruin the nation and condemn his people to tragic and avoidable suffering. Fénelon’s letter to Louis describes the tragedy. ‘Your people,’ he tells Louis, ‘whom you ought to love as your children, and who have been up to now so devoted to you, are dying of hunger.’ Better, Fénelon insists, never to have pursued these ‘vain foreign conquests’ and instead to have prioritised the people’s wellbeing over his petty self-interest: ‘Instead of drawing money out of these poor people, you ought to give them alms, and feed them.’

As a political reformer, Fénelon pushed back against Louis and worked to refocus French politics on the people’s needs. In part, this took the form of his bestselling novel, which sought to inspire its reader to love virtue and to become anti-Louis – an aim that would inspire later Enlightenment admirers of Telemachus from Jean-Jacques Rousseau to Thomas Jefferson. And in part, it took the form of direct resistance (as in his letter to Louis), and the plans for an alternative government that he drew up with his fellow resistors (the so-called ‘Tables of Chaulnes’).

Yet politics was only one side of Fénelon’s life. As mentioned earlier, Fénelon was also a prominent religious figure, and he remains one of the most important and insightful writers on spirituality in the long history of the Roman Catholic Church. And it is this other side, his philosophical and spiritual side, that arguably most deserves our attention today.

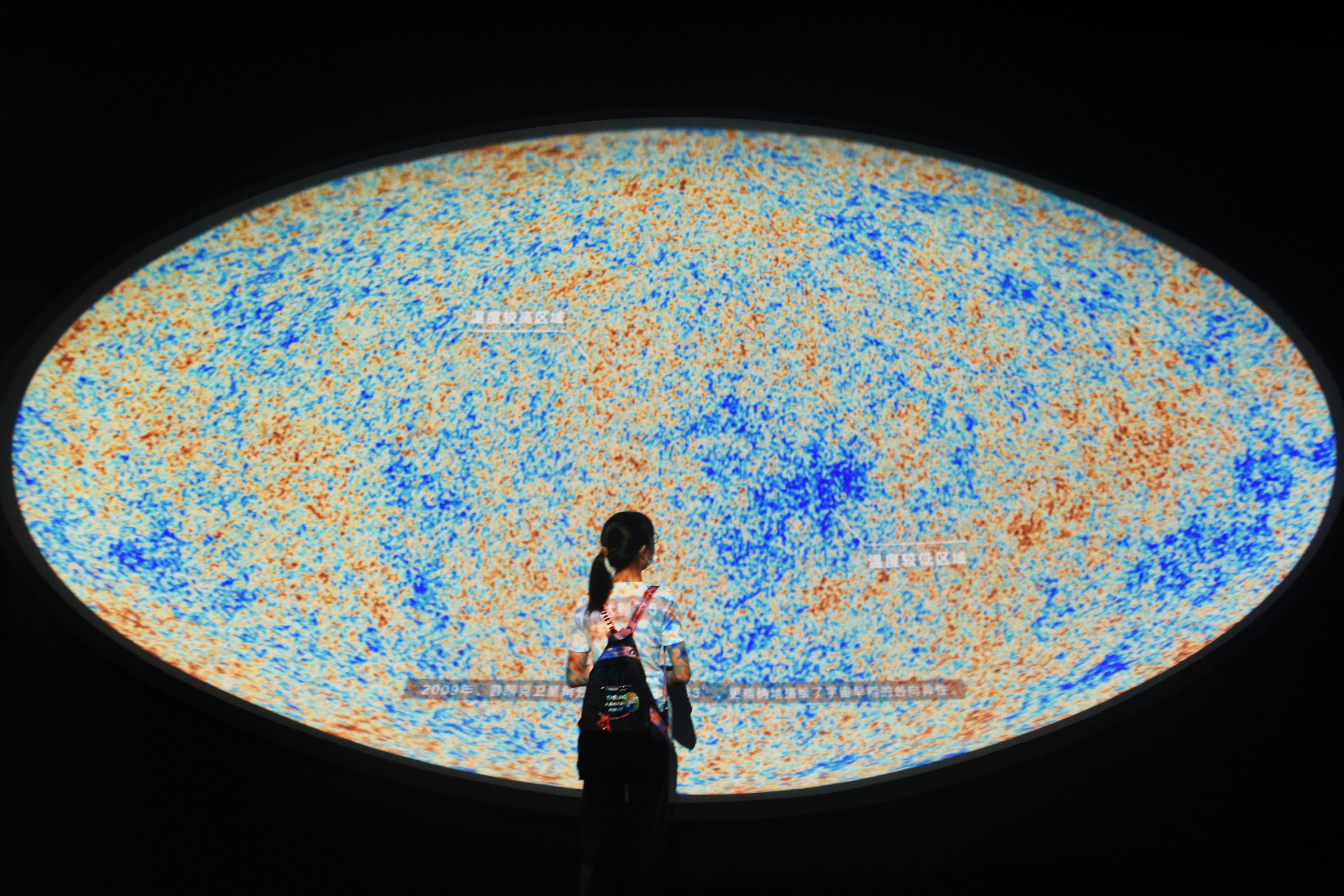

At the heart of Fénelon’s spiritual writings lies the idea of self-transcendence. The theology behind his concept of self-transcendence is complex, but the core idea is simple enough. Human beings, Fénelon thinks, are constantly pulled in two directions by two different types of love. On the one side stands self-love. Self-love, or amour-propre, is what prompts our obsessive concerns with the sorts of goods valued by our world: money, attention, status. On the other end of the spectrum lies a very different type of love. Pure love, or amour pur, is a love free of all self-love, one that seeks not the goods that our world values, but a good that is truly and absolutely good, possession of which can alone provide us a true and lasting happiness.

Fénelon himself – as one might expect of a 17th-century French Catholic archbishop – identified God as the object of pure love. In his account, the fundamental task of the human being who wishes to experience lasting joy and tranquility is the act of self-transformation that leads us from one love to another. If we hope to free ourselves from the anxiety and misery that plague our relentless pursuits of wealth and recognition, we need to liberate ourselves from self-love’s grip, filling its absence with the pure love that alone allows us to know peace and happiness.

This idea lies at the heart of Fénelon’s spirituality, and expressions of it can be seen across his sermons and occasional writings. But it comes out especially powerfully in his correspondence. Fénelon was a prolific letter-writer, and he was generous in responding to those who sought his spiritual advice. One of his frequent correspondents was the Countess de Montberon; in one of his many letters to her, Fénelon laid out his fundamental idea:

Amour-propre is impetuous, restless, reckless, and ensnaring. The love of God is simple, peaceful, direct. It speaks with a sweet and delicate voice. As soon as an ear is lent to the cries of amour-propre, the tranquil and modest voice of holy love can no longer be heard. Each love speaks only of its object. Amour-propre speaks only of the self, which it thinks is never treated well enough. It thinks only of regard, consideration, and esteem. It is put in despair by all that fails to flatter it. On the contrary, the love of God would like to see the self be forgotten, that it be counted for nothing, that God alone be all, that the self which is the god of the profane be trampled underfoot …

Fénelon’s advice to his correspondent is clear: real love, pure love, requires that we see our dear self as it is, and allow it to be ‘trampled underfoot’ – or, as he elsewhere says, allow it to be ‘annihilated’ – to make room for pure love.

Now clearly this is a daunting task. And even those persuaded that it could be worth the effort might wonder: how exactly does this work? Just how does one transcend the self? Fénelon’s key claim on this front is that this is a task that must necessarily be pursued in stages. And his clearest and most succinct account of these stages is given in one of his most important books, the Maxims of the Saints.

Fénelon wrote the Maxims of the Saints in 1697, in the midst of that heated battle over quietism that went all the way up to the Pope. A key issue was the orthodoxy of the concept of pure love, and in the Maxims of the Saints Fénelon sought to demonstrate its orthodoxy by showing how pure love harmonises with Church teachings. But for our purposes, the book is valuable for the path it traces from self-love to pure love.

In its introduction, Fénelon lays out the stages of the love of God. In so doing, he draws on an ancient conception, that of the ascending ladder of love – an image well-known from Plato’s dialogue on love, the Symposium (c385-370 BCE). In Fénelon’s account, the ladder has five rungs. The lowest is a wholly self-interested love of God, in which he is loved only instrumentally for the rewards he can provide. But this love can be purified in stages. And in time, these stages lead upward through the middle rung – the ‘love of hope’, in which self-love and divine love vie for supremacy – to the topmost rung: ‘pure love, or perfect charity’, in which God is loved ‘without any mixture of fear or hope or self-interested motivation’.

From all this, one might wonder: what does this mean for us? We live in a secular age, and far fewer now than in Fénelon’s day define themselves in terms of divine love. So what really can we hope to learn from a 17th-century archbishop? It seems to me that even secular readers – and especially the many who think that self-transcendence is worth working towards – can benefit from him. Fénelon’s account of self-love helps us see the limits of the self, and especially the ways in which self-love tortures us by fanning the flames of an unhealthy obsession with ‘regard, consideration, and esteem’. He makes clear that this obsession comes at tremendous moral and political costs – and challenges us all to do the hard work of defining for ourselves what exactly we hope to reach once we’ve left the self behind. You don’t have to be religious to be persuaded of the necessity of that great task.