In her memoir Crazy Love (2009), the American feminist writer Leslie Morgan Steiner details the domestic violence she suffered during her four-year relationship with her ex-husband Conor. He choked her, punched her, banged her against a wall, knocked her down the stairs, broke glass over her face, held a gun to her head, took the keys out of the ignition on the highway. There were clear warning signs early on in their relationship. While having sex, five days prior to their wedding, Conor choked her until she almost passed out: ‘His hands tightened around my throat … My eyes began to water. My body began to writhe involuntarily. Panic spread across my chest.’ ‘I own you,’ he told her before he came. Although she knew that she was about to marry a dangerous man, Steiner didn’t call off the wedding. She was in love.

As the title of the memoir makes plain, Steiner’s love is deeply irrational, verging on madness. Victims of domestic violence sometimes stay with their abuser out of fear of repercussions and backlash if they leave. This makes sense. But Steiner didn’t stay out of fear. Not initially, at least. When Conor broke a glass frame over her head, slitting open her face, her only thoughts were: ‘Don’t let this happen. I do still love him. He is my family.’ Staying with your abuser out of love, as Steiner did, is irrational because it vitiates prudential – or ‘self-regarding’ – concerns, which are the hallmark of practical rationality.

When Steiner’s memoir was first released, various commenters aired their objections to critical assessments of Steiner’s decision to stay with her abuser on the grounds that we shouldn’t blame the victim. Even when a victim worships her abuser for reasons of love, they argued, only the batterer is accountable for the harm inflicted. They are right, of course. Steiner clearly isn’t responsible for the abuse she suffered. But her delirious love for Conor impaired her ability to make rational decisions. This is the dark side of love.

As I have argued in my book On Romantic Love (2015), rational love – love that is sane, sound and sensible – is reason-responsive, grounded in reality and consonant with your overall mindset. These are lofty ideals but not unachievable goals. For love to be reason-responsive it must yield to reasons against it – reasons that your love is inimical to your interests. Your interests are those states of affairs that further your overall flourishing, or wellbeing. Performing an unpleasant activity might be in your best interest if it promotes your overall wellbeing. Think pelvic exams, colonoscopies and root canals – or breaking up with someone you are madly in love with. Despite knowing that Conor presented a threat to her safety and wellbeing, Steiner didn’t get out until she had suffered four years of domestic abuse. Instead, she rationalised the beatings and hid her bruises. Her love was immune to reason.

For love to be grounded in reality it must be based on an accurate perception of the beloved, not fantasy, reverie or illusion. Love fuelled by a projection of a saint-like idealisation on to the beloved is bound to dwindle once the image of unbending perfection disintegrates and the real person, with her unsaintly flaws, is left in its place. Sustained only by fantasy and illusion, love that idealises the beloved is void of rationality. Steiner’s perception of Conor is fantastical in its nature. Even after years of battery, she puts him on a pedestal, emphasising how brilliant, funny and fascinating he is, convinced in her naivety that he is her ‘soul mate’.

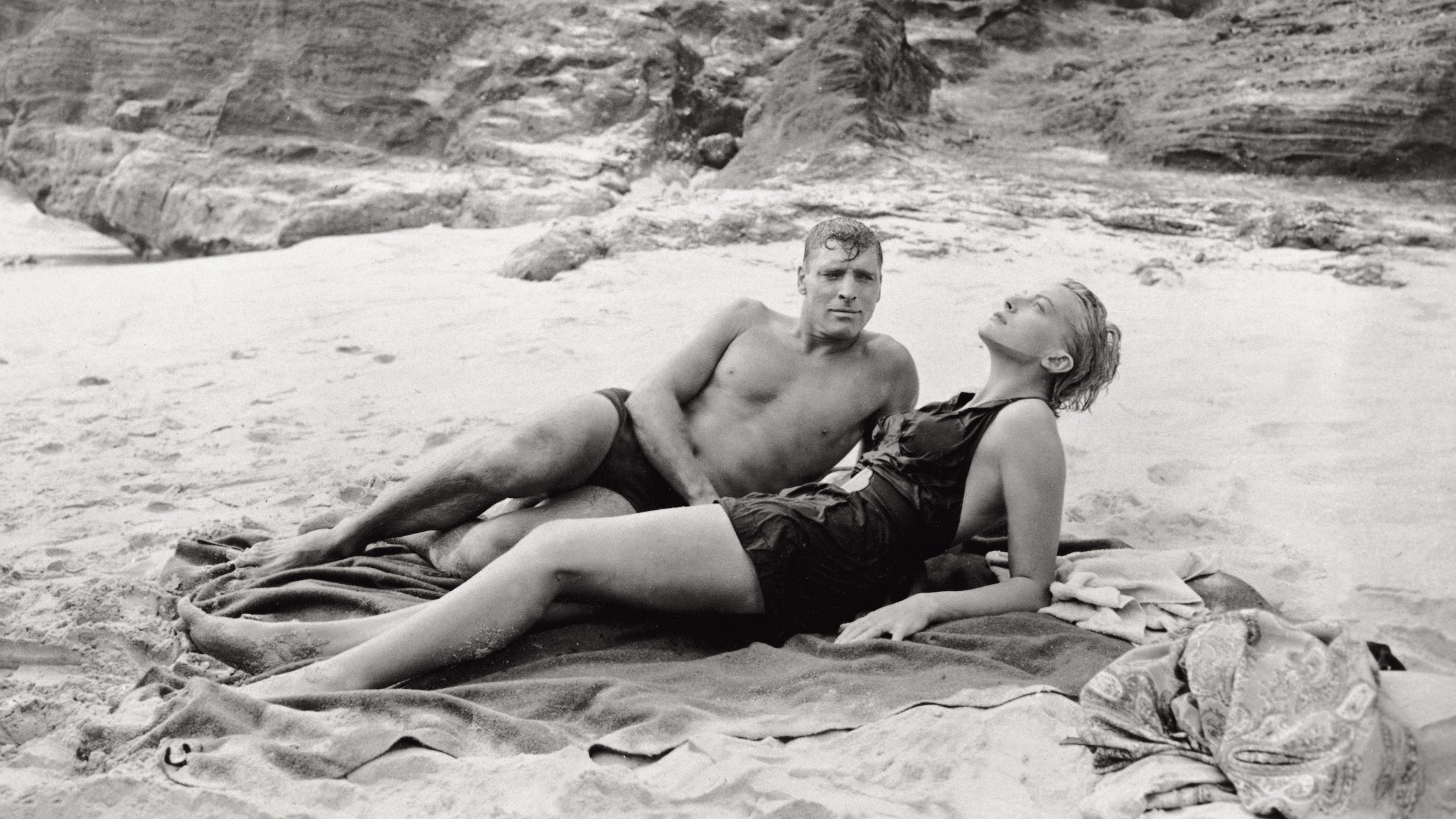

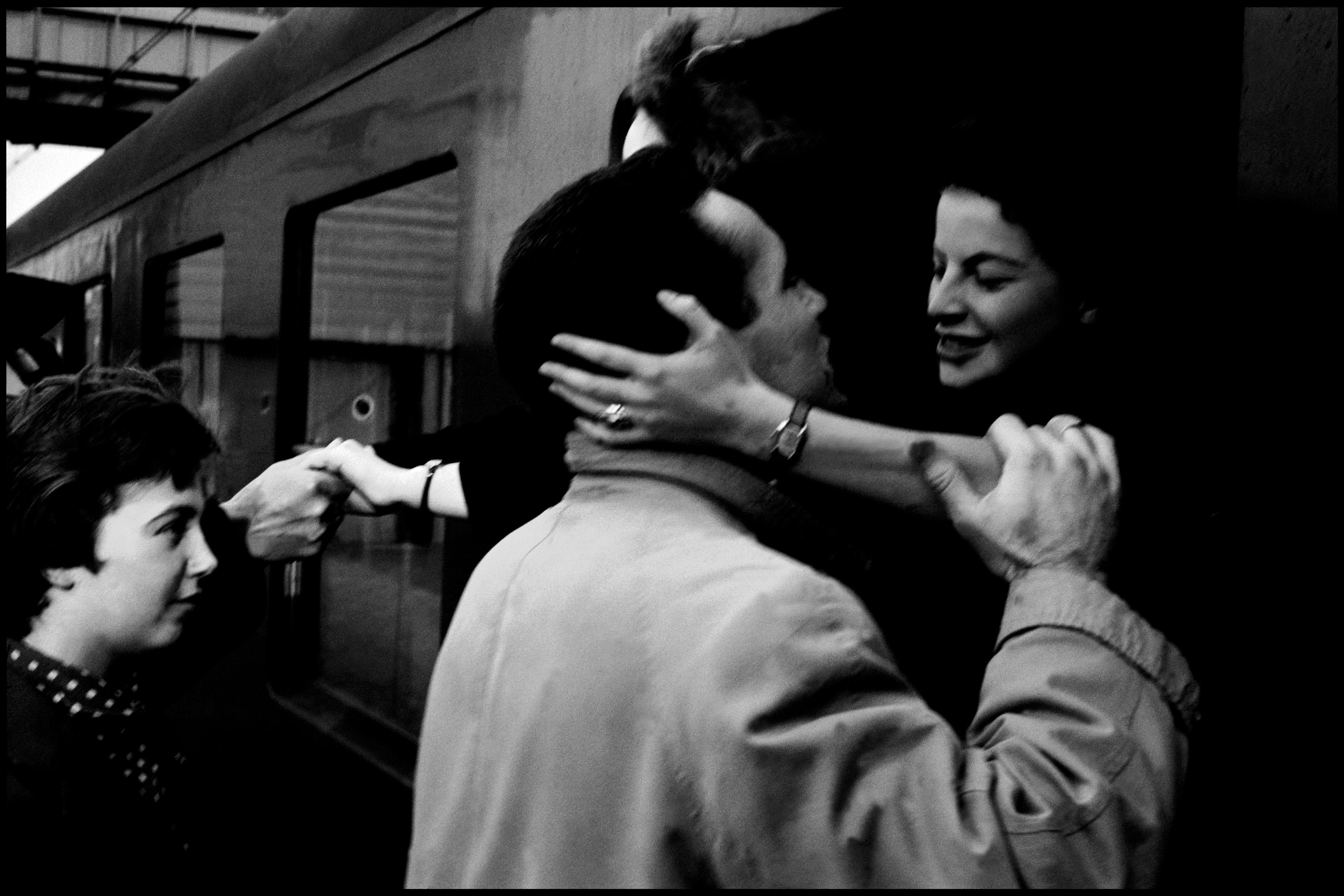

When we are madly in love, we close our eyes to the truth or edit it carefully

To be consonant with your overall mindset, love must cohere with your beliefs, desires and emotions and not breed internal inconsistency. The love part of love-hate relationships is a paradigm example of love that vitiates this ideal. To love someone is to have a strong desire to promote their interests. But when you hate someone, you don’t want to promote their interests, and probably want to impede them. Simultaneously loving and hating someone thus breeds internal inconsistency, or what is also known as ‘cognitive dissonance’. It’s a kind of defence mechanism, where you often suppress your hatred to avoid the uncomfortable realisation that your relationship is dysfunctional. During her four-year relationship with Conor, Steiner’s rationalisations of his egregious behaviour become increasingly riven with internal contradictions and efforts to suppress her own anger and hatred.

Crazy love forgoes at least one of these ideals, and sometimes all of them, as Steiner’s did. When we are madly in love, we close our eyes to the truth or edit it carefully before taking it in. We overlook obvious faults of character and personality. We leave our children, max out our credit cards and throw away friends, family and career. We put up with bad manners and rude behaviour, even violence. Alas, knowing just how costly crazy love can be doesn’t deter it from digging its claws deeper into our flesh.

Why don’t we avoid crazy love like the plague? Why do we, in fact, strive to fall so madly in love? The answer turns on our pesky brain chemicals: all-consuming love is coupled with a brain chemistry similar to that of people addicted to cocaine or methamphetamine. Taking the drug (ie, realising your crush has a crush on you, or spending an intimate afternoon with your sweetheart) leads to a hyperactivation of the brain’s dopamine system. But when your beloved is acting unpredictably, creating uncertainty about where you stand, the brain’s levels of dopamine plummet, and your stabbing pangs of longing numb your critical faculties and urge you to take desperate measures to restore balance. This is the mindset of an addict, a mindset that is hijacked by brain chemicals and is unyielding to reason.

Not long after meeting Conor, Steiner starts exhibiting the thoughts and behaviours of an addict. ‘It’s like jet fuel, being with him. It’s like we’re one person … I have never felt like this … I feel like the luckiest girl in the world.’ And at first Conor seemed like a dream come true. Not only was he handsome and smart, he was a real gentleman, projecting an image of unbending integrity: ‘He never reached over to pat my thigh or arm, as so many men did way too early.’ He even quit alcohol altogether when he found out that Steiner didn’t drink. Whereas her friends and coworkers ‘bemoaned their boyfriends’ fear of commitment’, Conor gave her a key to his apartment only months into their relationship. How masterfully he manipulates her. How quickly the idyllic relationship turned nightmarish.

There has been a major pushback against the idea of subjecting love to rational evaluation. The American philosopher Laurence Thomas, for example, has argued in his essay ‘Reasons for Loving’ (1991) that: ‘There are no rational considerations whereby anyone can lay claim to another’s love or insist that an individual’s love for another is irrational.’ This view is encapsulated in received wisdom in the form of sayings such as ‘Love is blind,’ ‘Love has no reason,’ and ‘Love is temporary insanity.’ We cannot lay claim to another’s love because, according to Thomas: ‘There is no irrationality involved in ceasing to love a person whom one once loved immensely, although the person has not changed.’

We don’t have any default moral duties to love anyone romantically

Is this widespread opinion correct? Is it irrational to stop loving a person ‘just because’, and not because the person has changed? Should we stay with people we once loved but love no more? Surely not. You shouldn’t stick around in a relationship with someone you don’t love, even if there’s no good reason not to love them. But the idea that love can be assessed for rationality doesn’t imply that you should do so. Rationality concerns your interests, not the interests of others. If you have fallen out of love with your partner, it is – all things being equal – in your best interest to end the relationship. That’s the logical thing to do.

What duties we have to others is a question of morality, not rationality. We don’t have any default moral duties to love anyone romantically. But promises, agreements, contracts and laws do sometimes bring into existence duties to love, and once you have an antecedent obligation to love another person, they can rightfully lay claim to your love. For example, you have a duty to take care of the basic needs of children in your custody, and love is a basic need. Similarly, if you marry someone, you enter into a contract that brings certain duties into existence, for instance, a duty to love, as articulated in the wedding vow that has taken root in American popular culture:

I, Gigi, take you, Lilly, to be my wedded wife, to have and to hold from this day forward, for better, for worse, for richer, for poorer, in sickness and in health, to love and to cherish, till death do us part.

So, if you enter into a marriage contract with another person, they can rightfully lay claim to your love. The marriage gives them a claims right, and if you fail to deliver, you are in breach of contract, and might end up as a defendant in a civil lawsuit. Be careful what you promise.

If your love puts your partner on a pedestal, turns a deaf ear to reason and makes you conflicted about your love for him or her, then you are in the grip of crazy, irrational love. Because we naturally crave the thrills and dangers of irrational love, choosing to call it quits can be hard. But if you stay in a toxic relationship, your mental and physical wounds may never heal. As the old saying goes, holding onto broken love is like standing on splintered glass. If you stay, you will keep hurting. If you walk, you will hurt, but eventually you will heal.