Think of the last time you felt uncertain about something important. Maybe you were concerned about the future of a relationship, about a confusing new medical symptom, or even about the future of the free world. As you likely experienced first-hand, the sense of not knowing, or of being unable to make a clear prediction, is often anxiety-provoking and attention-grabbing – and for that reason, many people think of uncertainty as an unpleasant state. But I hope to change how you think about uncertainty – and help you see that, if you never experienced it, you’d be ill equipped to cope in an uncertain world.

It’s important to recognise that not all uncertainty is the same, and how people respond to uncertainty depends in part on the type of uncertainty they experience. There are situations in which we may not know what is happening because the outcome of the event hasn’t been determined yet (for instance, your boss hasn’t decided who to lay off yet, or election votes are still being cast). But uncertainty can also occur when we don’t yet know what an outcome is, even though it has been determined (the people being laid off have been chosen, but you don’t know who they are yet; the vote has been collected, but the results have not been announced). Our responses to both these types of uncertainty illustrate the unexpected usefulness of experiencing uncertainty.

When the thing hasn’t happened yet

The difference between situations in which the outcome has or has not been determined is critical: after all, when the thing hasn’t happened yet, it could still be possible to influence it. Experiencing uncertainty in this context prompts us to see the situations where we can act to move undecided circumstances in a desired direction. If the boss hasn’t decided who to lay off yet, the sense of anticipation might be unpleasant, but it also means you may still be able to act in ways that decrease the likelihood that it is you.

One domain in which uncertainty can increase effort in this way is romantic relationships. For example, in one study, people desiring a romantic relationship with a particular person were asked to think about a time when they were worried their crush wasn’t interested in them – inducing uncertainty in this way led these participants to say they’d be more willing to exert effort in the relationship than a comparison group who thought about something less likely to trigger feelings of uncertainty (such as what their crush might do on a typical day).

Research confirms that people prefer to watch undetermined events live rather than recorded later

Other research has shown that on days when people in a dating relationship feel more uncertain about their partner’s feelings, they tend to post more about their relationship on social media, potentially as a way to invest in the relationship. Similarly, you might find that when you feel less certain about a desired or current relationship, you are more likely to plan a date, buy flowers, or at least post something sweet on social media. In short, uncertainty might be uncomfortable, but it can motivate us to put in the work for a desired outcome that hasn’t finished unfolding yet.

The motivational power of uncertainty is so entrenched that in some contexts people tend to prefer undetermined uncertain situations over determined ones, even when there is no way they could affect the outcome. You probably know a sports fan who will only watch ‘the big game’ live – and research confirms that people prefer to watch undetermined events live rather than recorded later. In one study, participants reported being most interested in watching a Bachelorette-style reality TV show if the show was both unscripted and shown live (providing maximum uncertainty about the outcome).

We often view undetermined situations as more desirable than situations in which an (unknown) outcome has been determined, in part because we feel some amount of (irrational) control over even objectively uncontrollable undetermined events. Imagine guessing the roll of a die. Would you prefer to guess before the die is rolled or after it is rolled (but before the result is revealed)? Most people prefer to guess before the die is rolled. This preference for predicting before the outcome is known is stronger in people with a greater belief that they can affect outcomes in life more generally. Are you this kind of person? If so, it could affect your attitude to uncertainty. For instance, say a committee is deciding whether you will be accepted to graduate school – you may prefer hearing they haven’t met yet, as opposed to being told they’ve met and decided but haven’t announced their decisions. This is because outcomes that are not yet determined may feel like they can still be influenced, even if this feeling is often irrational.

The thing has happened, but you don’t know how it went

Even if the thing has happened and the outcome has been determined, experiencing uncertainty can serve as a signal that you could benefit from acquiring more information.

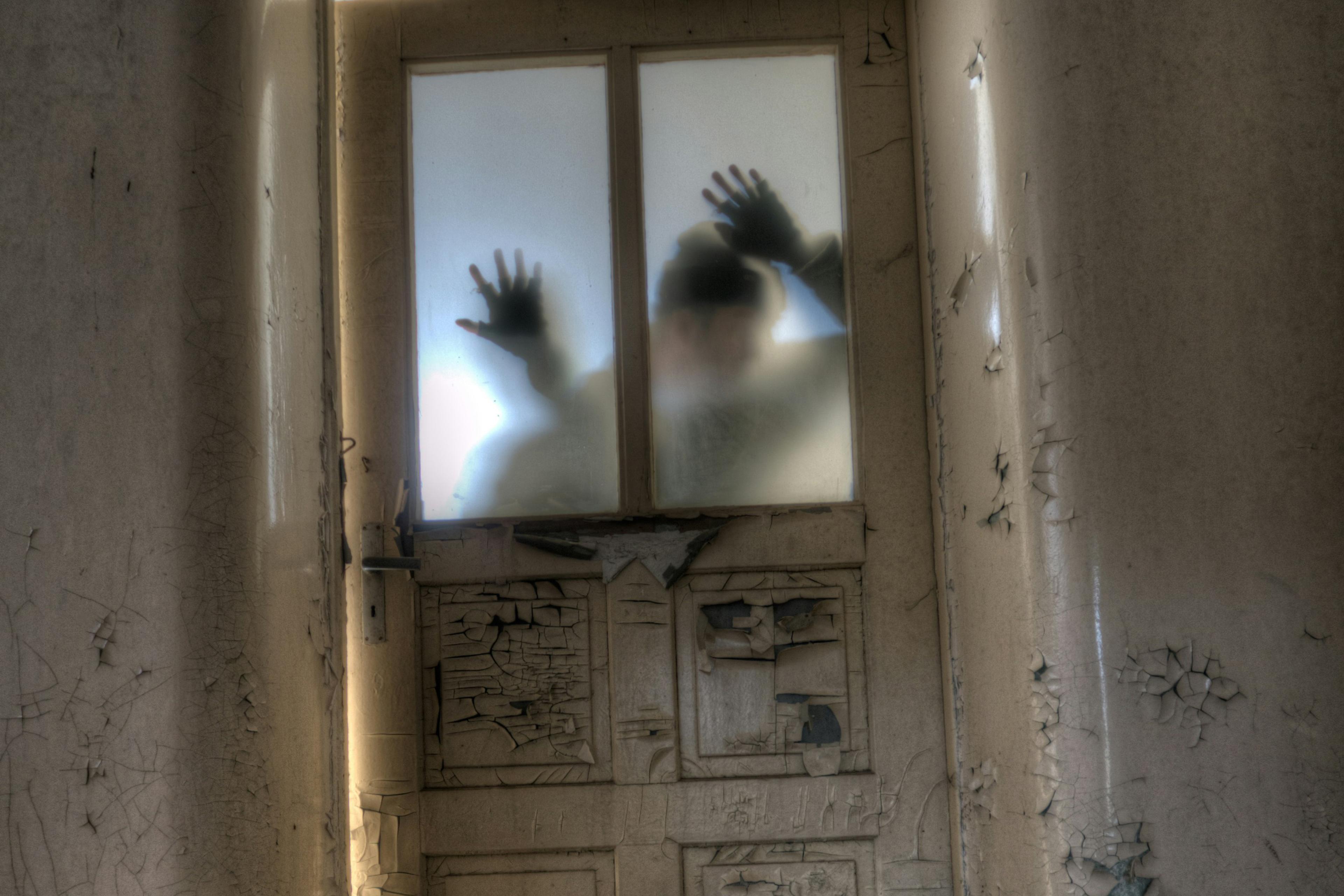

To help us gain more information about uncertain situations, our attention is attracted to uncertainty. In one study, participants viewed a series of pictures, each one being paired with an aversive sound either all of the time, never, or half of the time (this last group of pictures therefore had the most uncertain association with the sounds). Only some of the participants learned to recognise these different probabilities and they were the ones who spent longer staring at the 50/50 pictures. In other words, participants whose attention was attracted to the pictures with uncertain probabilities were the ones who learned more about the picture-sound contingencies. This is an example of how paying more attention to the things we can’t reliably predict (yet) can focus our energy on potentially making better predictions in the future. For a real-life equivalent, consider how figuring out the predictors of your boss’s seemingly unpredictable moods could allow you to choose the best moment to make requests.

Uncertainty can sometimes prompt us to seek out useless and harmful information

Even the stress triggered by less predictable situations can help us to learn. In one study, participants were asked to make a long series of choices between two rocks, one of which always delivered a safe but unpleasant electric shock. The probabilities of which rock (the one on the left or right) was more likely to deliver a shock stayed the same for a series of trials, and then switched. Physiological stress (measured by the sweat on participants’ fingers and the dilation of their pupils) and their subjective feelings of stress were highest for trials where the probability of one or other rock being electrified was closest to 50/50. More importantly, participants who experienced more stress when the rocks were more uncertain (closer to 50/50) were more likely to correctly guess the non-shocking rock than people whose arousal did not track the uncertainty of the situation, suggesting they’d done a better job of tracking the probabilities.

Outside of the lab, you can imagine how the increased stress you experience from interacting with a touchy, erratic family member, as uncomfortable as it is, could actually help you learn what conversation topics will be best received (thus avoiding the ‘shock’ of interpersonal conflict).

A word of caution

Although there is a function to uncertainty’s effect on attention and stress, there are also downsides. Uncertainty’s ability to capture our attention and increase stress is part of the reason why uncertainty over potentially devastating events can be so debilitating – for instance when waiting for a medical diagnosis.

Another caveat to uncertainty’s usefulness is that it can sometimes prompt us to seek out useless and harmful information. For example, interviews with private investigators found that 92 per cent of their clients had asked to see pictures of a partner cheating (in addition to receiving the information about the cheating), even though this was likely to only deepen their distress. Similarly, many of us have experienced succumbing to click-bait headlines (eg, ‘The Secret Killer in Our Waters’), even though we know at a rational level that hearing more about it is unlikely to benefit either our mental health or our decision-making. In other research, participants chose to see transcripts of an interaction partner’s criticisms, even though the participants admitted that reading them would do them more harm than good.

In a similar vein, people say they would advise a friend to avoid certain unpleasant information (eg, regarding whether a former romantic partner had cheated on them). Yet, if people are asked if they themselves would like to know this information, they say they would want to know.

The case for embracing uncertainty

These sorts of scenarios, where we would be better off without additional information, show how it can be beneficial to learn to sit with the uncertainty – rather than always seeking to remove it. There are other ways that we pay a price when we rush to avoid the experience of uncertainty. Consider research showing that people (and pigeons!) will often choose a suboptimal bet – where they will learn the outcome sooner – over a more advantageous wager, for which they will have to wait to learn the outcome. This is despite the timing of the delivery of the reward itself being held constant across both choices.

People who experience discomfort with uncertainty about information are also more likely to accept misinformation as true and claim familiarity with made-up concepts than those who are more comfortable with uncertainty. Impatience to resolve uncertainty could also result in settling for a less-good job, relationship or information than you could obtain if you could be patient in uncertainty.

Those who had to wait to find out which of two preferred gifts they’d won were happier for longer

Finally, discomfort with uncertainty has costs for mental health. People who are generally intolerant of uncertainty are more likely to experience depression, anxiety and suicide ideation than people who are less intolerant of uncertainty. For optimal mental health and decision-making, establishing some comfort with uncertainty is a huge benefit. One technique used in therapy designed to reduce intolerance of uncertainty encourages people to engage with relatively low-risk uncertain situations. Popping into a new exercise class, testing out a new technology, or introducing yourself to a stranger may build your tolerance of uncertainty.

If you decide to pursue experiences of uncertainty to increase your comfort with them, you may notice some unexpected benefits. Uncertainty can actually enhance positive experiences. Multiple studies have shown that uncertainty increases the duration of positive emotions. In one, participants were told they’d won a prize or even two. Crucially, those who had to wait to find out which of their two preferred gifts they’d won remained happier for longer compared with participants who were told right away which preferred gift they would get. Those participants who had to wait were even happier compared with others told right away that they’d actually receive both their preferred gifts.

It’s for this reason that Halloween ‘boo bags’ – where neighbours drop off gifts without saying who they are from – and ‘blind bag’ toys – where the exact toy inside is uncertain until it is opened – may brighten your (or your child’s) day a little longer compared with their less-uncertain versions. The attention-grabbing nature of uncertainty can work in our favour when it surrounds what we know will be some kind of positive outcome.

If you did not experience uncertainty in this uncertain world, you would be at a tremendous disadvantage. You would fail to give increased attention to your teenager’s recent erratic behaviour, vague construction detour signs, or that suspicious-looking mole, potentially leading to negative consequences. Uncertainty is also what allows us to get an extra spark of enjoyment out of secret admirers, wrapped gifts and suspenseful novels. Although uncertainty in the world is not always welcome, it is likely you will benefit if you can learn to be more aware of it and comfortable with it.