Sigmund Freud’s patients would often recline onto a chaise longue as they spoke, with him seated somewhere behind, free from the constraints of eye contact. But this wasn’t the only way he liked to work. Other times, Freud took his patients to the streets and green spaces of Vienna. He felt that walking side-by-side helped some of them loosen up and speak more freely than they might otherwise.

Fast-forward a century, and clients entering mental health services today will have a different experience. They probably won’t be asked to lie on a couch, but their therapy will almost certainly be indoors. There are many benefits of being inside: the therapy room is private, predictable, and can offer a sense of safety and containment. But this doesn’t work for everyone. Some of those who would benefit from therapy choose not to pursue it because the encounter feels too uncomfortable and exposing. For these individuals, the thought of sitting across from a therapist in an enclosed space is too daunting, pressurised and clinical.

I’ve seen the benefits of moving therapy outdoors. Before my clinical psychology training, I spent several years working with young people who were homeless, and the outdoors was an important therapeutic space. Many of the young people were initially reluctant to engage with psychological support. My colleagues and I had to be flexible about where to meet them and how to help, rather than arriving with preconceived ideas about what support should look like. We had therapeutic conversations with them on the streets of Birmingham, or ventured further afield, canoeing across lakes and climbing mountains on residential trips in the Lake District. When we went outside more formal settings, many young people opened up in a way we hadn’t seen indoors.

A small minority of therapists – mostly those in private practice – do offer talking therapy outdoors, often combined with indoor therapy. The outdoor locations vary: from rural trails and woodlands to urban parks and footpaths; from areas of natural beauty to the garden outside the back of a therapy room. Some therapists and clients sit down outdoors, some ‘walk and talk’; others combine talking therapy with gardening or outdoor pursuits such as climbing or hiking. In these sessions, nature can either be integrated into the therapy itself or provide a more passive backdrop. When these therapists describe their experiences, many report that, for some clients, the outdoor space is as effective, if not more effective, than therapy indoors.

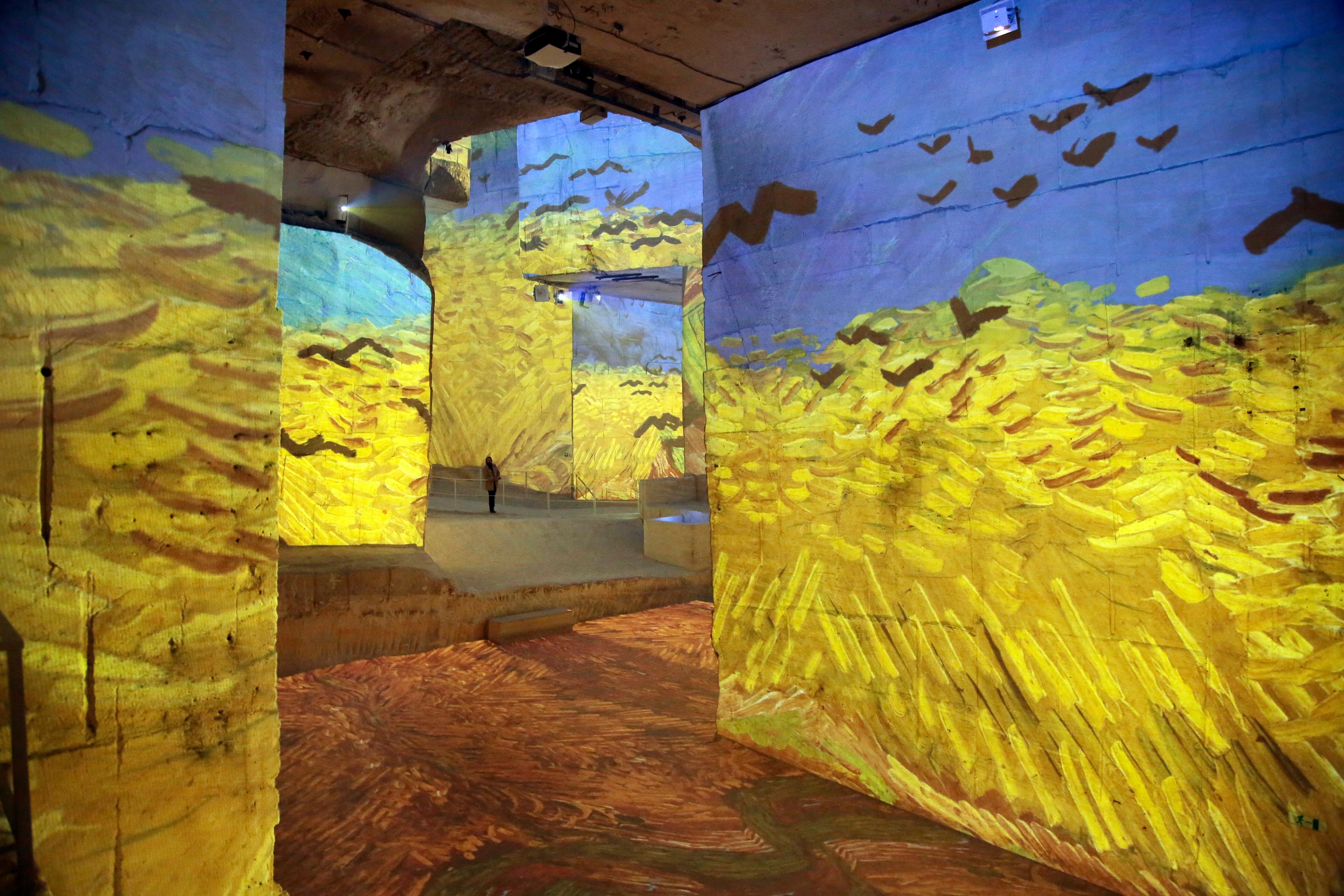

There are many reasons why this might be true. As a species, we have spent 99 per cent of our existence as hunter-gatherers, immersed in the natural world. In 1984, the American biologist Edward O Wilson popularised the idea of ‘biophilia’ – that humans have an innate need to connect with the natural world, even when it has been stripped away by industrialisation and urbanisation. One possibility is that this deep-rooted appeal means that outdoor therapy provides a special form of connection, safety and predictability.

Human problems can sometimes feel less overwhelming outside. Nature holds a position of indifference towards our human flaws and vulnerabilities, allowing the stress and humdrum of modern life to be viewed as only one part of our broader existence. Nature therefore possesses a unique power to liberate people and free up alternative perspectives. In one study, a participant who had group therapy in the remote wilderness said that the setting enabled him to ‘detach from the rest of the world, and clear [his] mind’; a therapist commented that people open up more easily in nature. In another study, clients described how a revived connection with natural spaces provided them with a therapeutic location to return to after the therapy has ended.

Many therapists don’t have access to nearby green spaces, and instead venture out into more urban environments. Even in the absence of nature, there is freedom while walking. In a study of those who use ‘walk and talk therapy’, one therapist described how, during ‘the walking and talking, [a client’s] mind and body are integrating … If they are stuck in something I just find that walking forwards and being in motion helps.’

Yet despite this rich outdoor environment, the majority of mental health therapists remain indoors. Some worry that their conversations will be overheard, breaking client confidentiality, or that weather conditions might be uncomfortable and distract from the therapy. Others are concerned about the extra time it might take to move between clients. Some therapists want to offer therapy outdoors but are prevented from doing so by the traditions of the services they work in.

In addition, outdoor therapy might be unsuitable for certain clients or difficulties. In a study exploring therapists’ perceptions of ‘walk and talk’ therapy, participants reported, for example, that dealing with trauma would be difficult. One therapist said: ‘I wouldn’t want to process traumas on the trails. I think sitting in an office in a contained space is more ethical.’

However, those who have experienced outdoor talking therapy find some of these barriers to be less problematic than expected. Many potential risks are mitigated through appropriate preparation and careful selection of the outdoor location. Therapists also recommend a transparent and ongoing process of consent, where potential risks (such as meeting another person on a walk) are discussed in advance with the client.

If the client or therapist thinks that going outdoors is too risky or uncomfortable, then they can, of course, stay inside. But just because outdoor therapy won’t suit some clients, therapists or difficulties, it shouldn’t be written off for others. Across mental health care, there is no universal approach that suits everyone. For example, some people might favour cognitive behavioural therapy over psychodynamic approaches; group over individual therapy; or face-to-face over digital consultations. Choosing the location of the therapy – indoors or outdoors – is no different.

Therapists already offer person-centred treatment – care that is moulded around the client’s individual needs. In most cases, this tailoring occurs for the content of therapy: what is talked about, and how it is approached. The context of where this talking happens should also be discussed, because the confines of the therapy room might put off some people from seeking help at all. If the great outdoors feels appropriate for the client, then therapists should be free to follow in Freud’s footsteps and walk beyond the therapy room.