After those long, cold winters in my northern city, summer days mean celebrations, gatherings, joy. But on this steamy July night, loud with people and music, the revelry filled me with dread. Our family had a history with people getting out of control. My kids, both young adults, were hosting a party in the apartment above mine. Over the cacophony, I suddenly heard my daughter yelling my son’s name, and my heart skittered. I raced upstairs, and found him in a hallway, a ghost version of himself, staggering out to the balcony. ‘You don’t even know me!’ he shouted as he stepped to the edge. Before we could get to him, he glanced back at us one last time, then hauled himself into the black toward the cement below. I screamed his name, part of me falling toward the pavement with him.

For the red-eyed tree frog, coming into the world involves falling. The mother frog lays her eggs on a wide, flat leaf dangling above a pool of water and, soon after, the male fertilises them. Upon hatching, the tadpoles’ first act is to plunge, sometimes many, many feet, into water below. Unlike most human beings who fall a great distance, the tadpoles are built to survive the impact. Once in the water, they develop into froglets and, if they are not eaten, they eventually crawl onto the banks as the beloved neon-green tree frogs with long red fingers.

Things had always been precarious in my son’s life, partly because of me. The year he was born, his dad and I were renovating a ramshackle two-storey farmhouse built in the early 1900s on a steep incline of a wooded valley. A train track threaded the hollow. We had secured the chicken coop and purchased some bantams and cochins. Our dogs kept other critters from eating them for the most part. Our garden had produced potatoes, tomatoes, basil and squash the previous fall. Lilacs and phlox along the wild edges of our property were beginning to bloom.

My mother told us about a ‘haunted’ house several miles away across the river where, many years earlier, a man had lost his mind and killed his family. Kids from the local school would drive out there late at night for the thrill. But that story had not dampened our dreams.

In an hour, my husband held a new person swaddled in hospital blankets up to my face

By the time I was ready to give birth, I had painted a baby’s room green, planted peas and spinach. We had baby blankets and books that we wanted to read to our child, including Frog and Toad.

I was optimistic about having a natural childbirth but, after my labour stopped progressing, the doctor began giving me higher and higher doses of the synthetic hormone pitocin to stimulate contractions. After a final shot, my body surged briefly but suddenly drained, like a plug had been pulled and my life was emptying out. All my vitals had dropped. My baby’s vitals had dropped. The nurses scurried around.

They wheeled me down a fluorescent-lit hallway toward surgery, strapping my seizing body to a metal table, my arms slamming like fish when they’re first caught. Somehow, in an hour, my husband held a new person swaddled in hospital blankets up to my face. My son had made it. I tearfully thanked the Universe. And, after several perilous hours, I came through as well.

Back at our little farmhouse, I suffered with a spinal headache and could not sit up at more than 45 degrees without searing pain, but I was so happy my son and I were alive. I managed to get outside so he could smell lilacs, feel the spring breeze on his skin, hear doves and chickadees. In the evenings, spring peepers and bullfrogs sang loudly and, occasionally, the mournful whistle of the train spooled through the valley.

At the time, his father was working and going to night school about 20 miles from our house. One evening, a little over two weeks since we got home from the hospital, my husband called on the land line. He asked if I was OK, his voice a bass clarinet, and told me to bring the dogs in, lock the doors, and that he would be home soon.

When he burst through the door later, he embraced us, explaining that earlier that night, a little over a mile from our house, a newlywed couple had been murdered in their home. Police suspected the Railroad Killer.

How could I run from a serial killer with a baby in my arms when I had this incision?

In the weeks afterward, a swarm of media people and FBI agents settled on the nearby town. Rumours of the murder spread, and every conversation turned to the terror. ‘Still on the run.’ From the windows in my house, I stared out at the outbuildings, watching for any sign that he was hiding on our property.

After the emergency C-section, for the first time in my life I didn’t trust my body. How could I run from a serial killer with a baby in my arms when I had this incision? For my son, I was brave. I sang to him, held him on my shoulder as he slept. To others, I seemed fine, but inside I was in a state of utter vigilance. Even after they discovered the murderer was an ex-boyfriend, not the Railroad Killer, and even after he was caught, my adrenaline never slowed.

My own childhood experience had shown me that the world was unpredictable, often violent. After my father left, my siblings and I survived life with a dangerous stepfather, who once threw a cat off our third-storey apartment balcony because she was irritating him. That marriage did not last long. Poverty itself is precarious, a constantly shifting ground. All I wanted was to protect my child.

We sold our dream farm and moved to a small town to start fresh. During my son’s early years, I found solace on my mother’s wooded land. We walked endlessly along the creek, and he played in those waters, falling in love with all that lived there, especially the frogs.

My son’s love of frogs emerged without any encouragement from me. His first sentence demanded a frog toy he loved be taken out of danger. Unusually shy, he astounded us one day when he was about five and saw an older boy dangling a frog from his hands in a local park. My son ran up to the kid and started shouting at him to put the frog down. The other child was so startled by the outburst, he obeyed. After his dad and I divorced, my son, his sister and I travelled a fair bit for my environmental research. My son found frogs in every landscape we visited, from Oregon to India. By the time he was in high school, he knew the life cycles and names of scores of frogs and had contacted several frog experts around the world to learn more about their endangered status. He intended to pursue their conservation.

He was bleeding and dazed, but alive, then up and staggering, yelling to leave him alone

As much as I wanted to, I couldn’t keep him safe from the world. He was bullied at school, assaulted at gunpoint, hurt by people he trusted, but he always forgave others. And, unlike me, he was fearless. He skied fast, raced mountain bikes, and obsessed over poison dart frogs. By the time he was 23, the planet was warmer than ever, frogs were facing extinction, and he had lost six friends to violence, car accidents, and drugs. Once, he had attempted leaving this world himself. And then, that July, he threw himself off a roof.

By some miracle, he landed on a wooden bench. He was bleeding and dazed, but alive, then up and staggering, yelling to leave him alone. ‘Remember who you are!’ I commanded fiercely through my tears, trying to hold his gaze. Eventually, his body crumpled with sobs he had kept in for years.

Numbness can be a survival strategy. There are frogs in the north woods of the US that can freeze themselves, slow down their system enough that part of their bodies become hardened to survive the difficulties of winter. They are living, but barely. When spring finally comes, they warm and reanimate. Both my son and I had numbed ourselves in different ways, but I had an idea. I knew a Costa Rican red-eyed tree frog conservation expert named Henry Pizarro Espinoza, and I decided we should visit him.

The jeep’s headlights illuminated tattered palm leaves as we bounced over the narrow mud road. Henry drove. We were headed to his frog conservation area, which he had created on deforested land. Beyond the envelope of light made by our vehicle, the forest was a dense tangle of black and kelp-green, an impenetrable wild that only hours ago – suffused with light – was a picturesque rainforest studded with an occasional scarlet macaw or iridescent blue morpho butterfly. When the humid air came into the jeep ringing with insect song and mystery, I felt the familiar tingle of adrenaline.

As we walked into the thick vegetation of the dark jungle, our flashlights illuminated circles of the narrow leaf-littered path, and Henry pointed out things he had planted: pineapples, bananas, heliconia, avocados, cinnamon, cacao. I was fascinated but watchful. This was also home to the fer-de-lance, a deadly viper. My flashlight was an extension of my active mind, flickering up tree trunks and back to the ground. Henry paused, smiling. ‘Listen,’ he said, and we heard the chirping lullaby of red-eyed tree frogs in the trees above.

Henry spotted a sleeping sloth, two racoons, and then took us to the bank of the river where he had seen an enormous crocodile earlier that day. He insisted that all the creatures in the ecosystem were important and worthy of being honoured, even the dangerous ones. You just needed to give them space and respect. I knew he was right, but still my eyes darted across the grey water. Nothing.

My son uttered the sigh of someone encountering the sacred. ‘So beautiful,’ he whispered

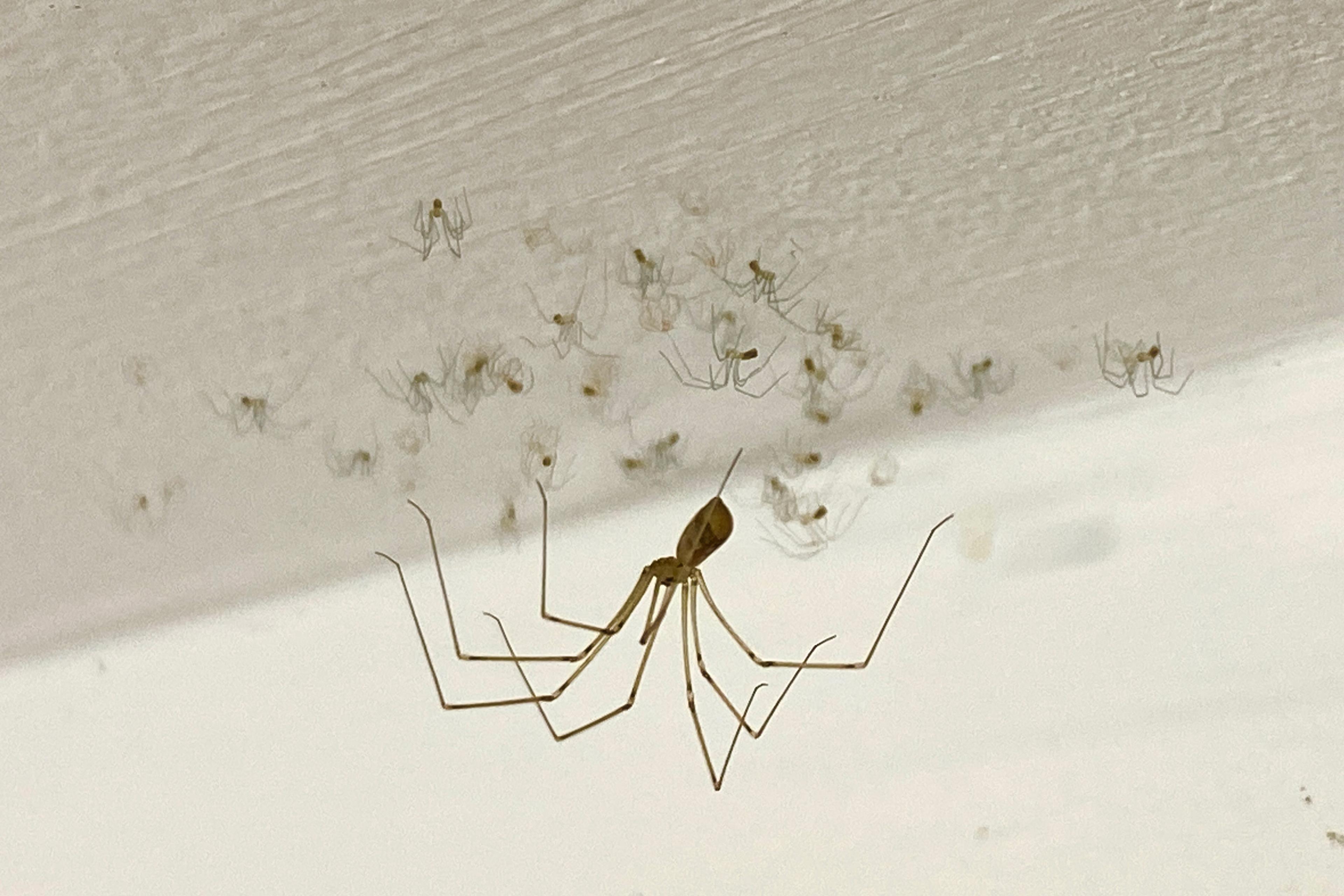

In a stand of bamboo, Henry noticed half a dozen huntsman spiders the size of my palm on the various poles. If we held our flashlights at eye level, the spiders’ eyes seemed to be gleaming back at us. The huntsman spider has a bite that can numb your whole arm. Henry plopped down his spotting scope so we could get a closer look. I leaned over the eyepiece and came face-to-face with a giant arachnid. Fine grey hairs and intricate lines framed a beautiful strange face. I was dazzled.

Tree branch in one hand, camera in the other, my son carefully photographed a glass frog resting on the inside of a hibiscus flower. Moments later, he leaned in to photograph a delicate and deadly Brazilian wandering spider the size of my fist.

Suddenly, Henry was saying my son’s name, his scope propped up next to a small pond with giant heliconia leaves hanging over the water. ‘Look in here,’ he said. My son complied and uttered the sigh of someone encountering the sacred. ‘So beautiful,’ he whispered, then gestured for me to look. In the scope I saw a cluster of red-eyed tree frog eggs, like tiny glistening jewels, stuck to the leaf, their red and green-gold bodies quivering inside. Soon, they would emerge and fall a great distance into the water below. If they survived initial impact, they would transform from tadpoles to adult frogs and live their best lives on Henry’s land.

On a hike the next morning, my son was quiet, taking slow intentional steps up a muddy path. ‘What are you thinking about?’ I asked him.

‘There was nothing here, but Henry planted the right things, and the insects and the animals returned. Birds, frogs, mammals. Gives me hope,’ he said, pausing to look at me. Then he turned and kept hiking.

The sun was already hot as we climbed. Two toucans chattered in a tree nearby. Spider webs gleamed in the sunlight. We were alive. While there were no guarantees, like the red-eyed tree frog tadpoles, we had plunged into a new beginning. I understood then: there is no compass but love.