Human hatreds take on a depressing variety of forms: in addition to individual hatreds, the world roils with xenophobia, racism, misogyny, homophobia, transphobia, and on and on and on. Less remarked upon is an underlying zoophobia – a fear of, or antipathy towards, animals – that’s manifest in many of the slurs and insults directed at other human beings. Calling a person an animal is usually a comment on their unrestrained appetites, especially for food (‘like a hungry animal’), for sex (‘they went at it like animals’), and for violence (‘they’re like wild animals’). We also have purpose-made insults comparing people to specific kinds of animal: pig, chicken, rat, cow, slug, snake, cockroach, bitch, etc.

But aren’t humans notorious animal lovers? How do these insults square with the sentimental affection people profess for pet cats and wild tigers alike? The fondness for beloved pigs like Wilbur and Babe and the insult of calling someone a ‘swine’ have more in common than first appearances suggest. Both the sentimentality and the insult rest on distortions that reinforce notions of human supremacy. The parallels between assertions of human dominance over other animals and over other humans are striking, and worth a closer look.

The mode of thinking that associates animals with unrestrained appetite is at least as ancient as Plato. What separates humans from the other animals, on this line of thinking, is our rationality. Plato conceives of the human soul as composed of three parts: the reasoning part, which loves the truth and seeks to learn it; the spirited part, which loves honour and is prone to anger; and the appetitive part, which attends to bodily desires.

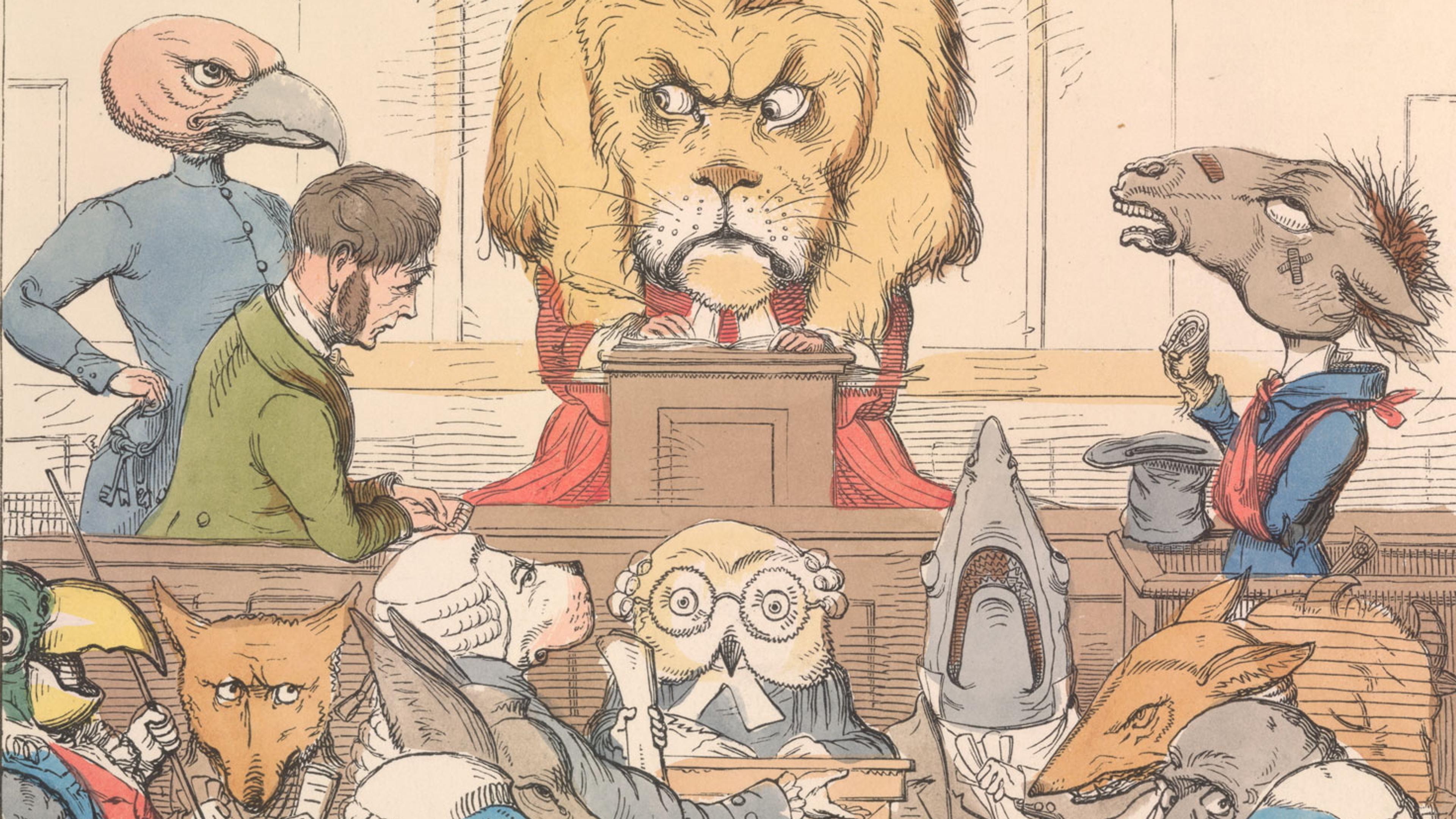

In the Republic, Plato pictures the tripartite soul as three different creatures enclosed within our human frame: a rational human, an honour-loving lion, and a terrifying multi-headed beast, like one of the monsters from Greek mythology. Some of the heads of this beast are of gentler animals and some are of wilder animals, and they shrink and grow depending on how they’re fed. A just person submits to the rule of the best part. But when the ‘beast within’ runs free, all hell breaks loose:

Then the beastly and savage part, full of food and drink, casts off sleep and seeks to find a way to gratify itself. You know that there is nothing it won’t dare to do at such a time, free of all control by shame or reason. It doesn’t shrink from trying to have sex with a mother, as it supposes, or with anyone else at all, whether man, god, or beast. It will commit any foul murder, and there is no food it refuses to eat. In a word, it omits no act of folly or shamelessness.

This way of picturing the soul makes us out to be two-thirds animal and one-third human. In this conception of human nature, the animals don’t come off well. If the only thing keeping us from rape, pillage and murder is the controlling hand of our highest, rational part, and if animals lack this rational part, then animal nature comes off looking, well, beastlike. Hence Plato’s fevered fantasy of the omnivorous, omnisexual, omnicidal monster who seeks sensual gratification without shame or reason.

Plato’s myth recognises that not all animals are equal. Not only does the lion come out looking pretty good but, among the multiple heads of the monster of appetite, Plato marks a distinction between domesticated and wild animals. The animals are emblems of how we might fail to live up to our human calling and those failings, on Plato’s telling, are diverse. So, as we’ve seen, are the varieties of animal insults that target different humans.

Let’s start with the wild animals. Plato’s vision of non-rational wild beasts has played a significant role in xenophobic rhetoric. Champions of colonialism likened Indigenous populations to wild animals – the word ‘savage’ has etymological links to wilderness and forests. Like wild animals, these people were said to lack the rational capacity for self-governance or participation in the political community. There’s no reasoning with them – all you can do is subdue them or destroy them. We find a descendant of this idea in anti-immigrant rhetoric that likens migrants to wild animals. They’re the predatory outsiders, the proverbial foxes in the chicken coop that we need to keep from entering our communities for fear of the damage they’ll do.

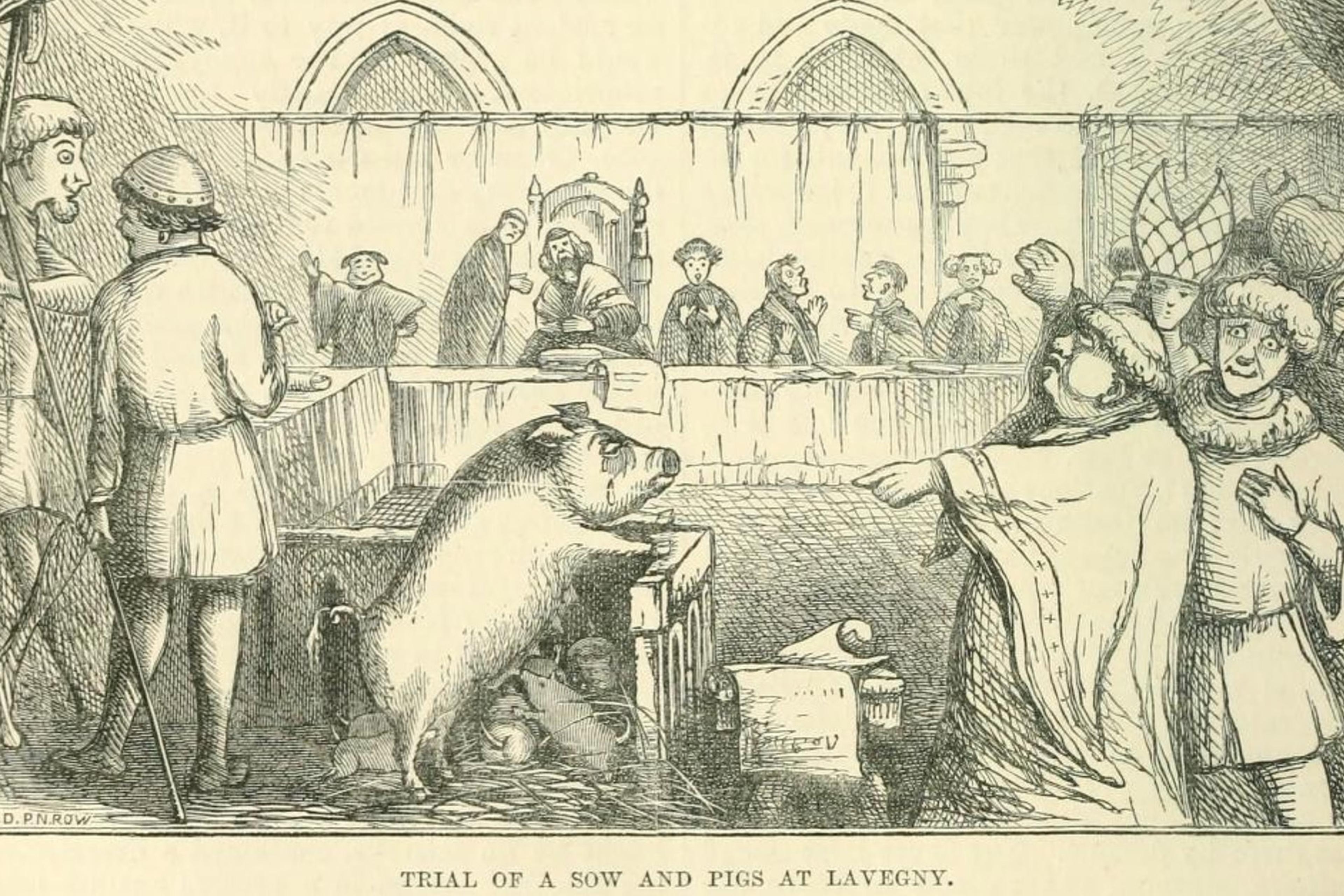

Other animals belong to our communities – hence the chicken coops – and they feature in pejorative language of a second kind. Domesticated animals provide a service to the human community – they’re sources of meat, eggs, milk, wool, and, before the advent of heavy machinery, they were essential to transport and farming. But this service is purely bodily. Their place in the human community is essentially subordinate.

No coincidence, then, that comparisons to domesticated animals reinforce subordination within the human community. This is especially evident in misogynistic language. In her book The Sexual Politics of Meat (1990), Carol J Adams documented the various ways in which women are compared to animals raised for meat and for the ‘feminised protein’ of milk and eggs. To call a woman a cow is at once to call her stupid and to reduce her to her gendered role as a source of milk. Unlike xenophobic rhetoric, which targets outsiders, misogynistic rhetoric takes for granted that women are essential to the flourishing of the community – but implies that, like domesticated animals, they must be kept in their subordinate place.

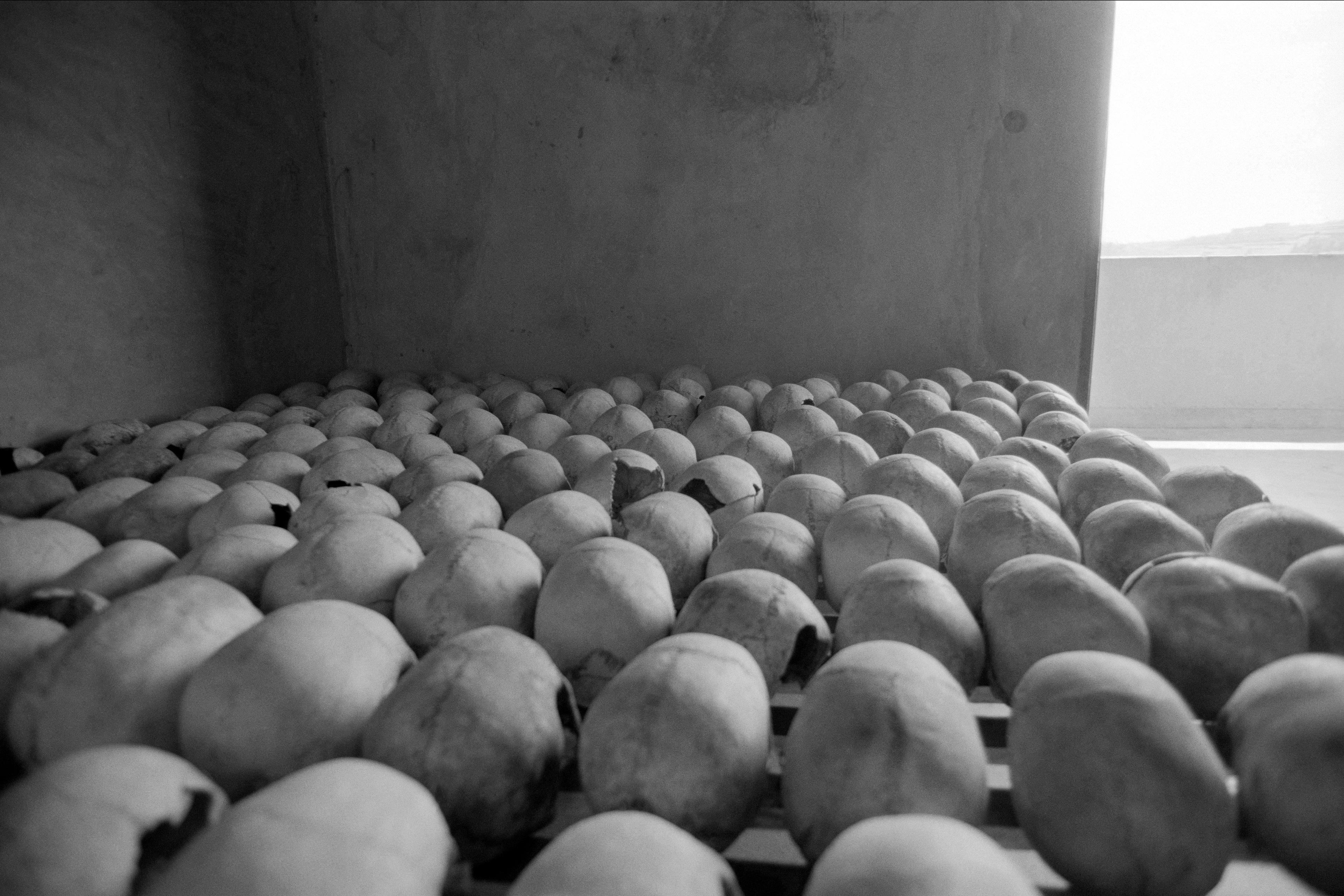

Plato distinguishes between only wild and domesticated animals, neglecting a third category of animal, which lives within the human community without belonging to it. In their book Zoopolis: A Political Theory of Animal Rights (2011), Sue Donaldson and Will Kymlicka call these creatures ‘liminal animals’. For the most part, people don’t like them, especially when they’re in the home. Rats and cockroaches are ‘vermin’ who take without giving, spoil food, and spread disease. They’re also a favoured trope of a different kind of xenophobic rhetoric, this time targeting the enemy within. Hutu Power propagandists during the 1994 genocide in Rwanda incited violence against Tutsis by comparing them to cockroaches. Nazi rhetoric frequently compared Jews to vermin. Where wild predators inspire fear, vermin inspire disgust.

Three kinds of human denigration – the unruly outsiders who have to be subdued or kept out, the subordinate insiders who have to be kept in their place, and the unwelcome guests who have to be expelled or eradicated – matched with three kinds of animal – wild predators, domesticated chattel, and vermin. The distortions that are required to degrade humans and animals complement one another. Recall Plato’s myth of the ‘beast within’. No actual animal fits the profile of this imagined beast. Natural selection would make short work of any creature that comported itself according to Plato’s description. But if animals are nothing like the beasts of popular imagination, that also means that there are no such beasts lurking within us. I’m not one slip of the executive function away from barbarity. My untamed impulses can also be loving, or just plain lazy. And if I do undertake a bit of rape and pillage, it wasn’t a beast within me that did that. It was me. Mary Midgley, who in her book Beast and Man (1978) does an elegant job of unpicking this mythology of the ‘beast without’ and the ‘beast within’, calls the latter ‘a scapegoat for human wickedness’.

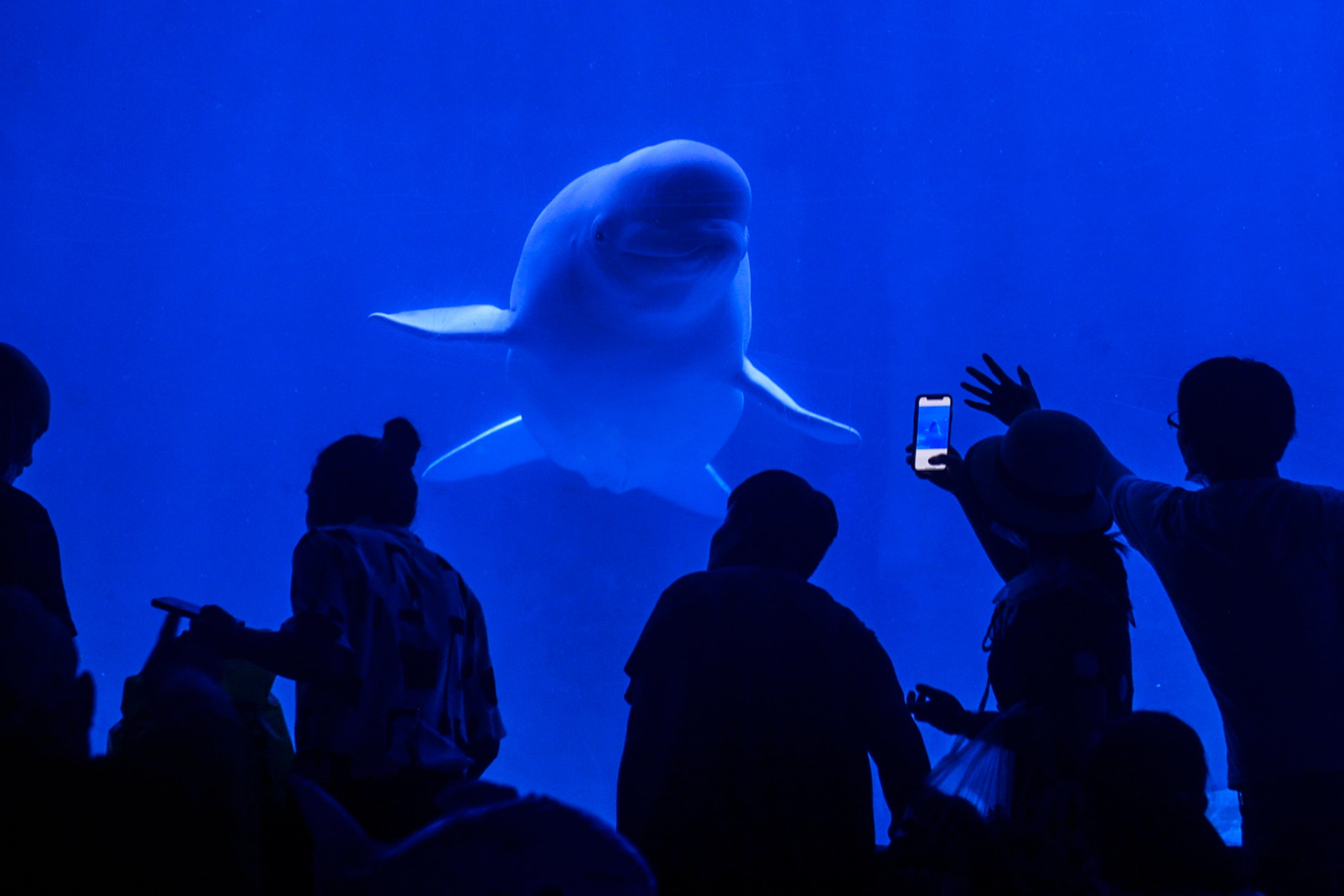

But what about the less hateful attitudes that humans have toward animals? People spend billions on preserving habitats for wild species and billions more on pampering domesticated pets. Not even all liminal animals are hated – squirrels and songbirds usually get a pass. To see the dark side of these forms of affection, consider again the human parallels. White settlers produce and consume an abundance of kitsch sentimentalising Indigenous North American cultures while perpetuating the suppression of those cultures. Like wild animals, Indigenous people are loved in the abstract and at a distance – in effect, when they don’t come too close. Likewise, misogyny has its sentimental side. Terms of endearment such as ‘babe’ and (tellingly) ‘my pet’ express affection while also reinforcing a power differential. Your pet – whether human or animal – doesn’t get an equal say how you run your home. When we see it in parallel with human-to-human condescension, affection for animals appears more clearly as just the gentler side of zoophobia.

When we invoke animals to demean our fellow humans, we also thereby reinforce an underlying conception of animals as contemptible. In most areas of dense human settlement, wild predators have been hunted to extinction. Most livestock live out a short existence in conditions so hellish that agricultural lobbies have pushed for so-called ‘ag-gag’ laws that criminalise their documentation. Rodents and many other liminal animals are exterminated remorselessly.

In ways both obvious and subtle, our language desensitises us to this cruelty. Consider this familiar protest against inhumane treatment: ‘They were treated like animals.’ If being treated ‘like animals’ means being treated with cruelty or neglect, we shouldn’t treat animals ‘like animals’ either. Amending our language so that ‘animal’ ceases to be a byword for contempt won’t in itself transform human behaviour. But it might be a start.