The internet is our community theatre. Especially during COVID-19 lockdowns and the stumbling recovery of in-person entertainments, amateur videos have become the site for a vital, if distributed, sociality. On TikTok and Instagram Reels, we watch everyday people – adults as well as children – play. For all the polished, perfect videos made by professional influencers, there are hundreds of thousands of others. There’s a big mess of kids’ toys and dog blankets in the background. The lighting is awful. The sound cuts out. The camera shakes. The US playwright Sarah Ruhl explains that ‘social ties’ are the reason we go to see community theatre, not good reviews. On stage and on the internet, neighbours and friends are transformed into heroes and villains. It’s not always pitch-perfect, but here we can try on new ways of being – and being with each other.

In the 1840s, a similar interest in amateur play took hold in the United States. ‘Home amusements’, as one guidebook dubbed them, ranged from elaborately scripted and staged theatrical entertainments and living pictures (tableaux vivants) to simple charades, pantomimes and optical illusions. At a time when perfecting genteel codes of behaviour promised upward social mobility, the closed rehearsals of at-home entertainments were crucial for climbers who wanted to avoid failure on a more public social stage. Amateur players could try on aristocratic airs without fear of being outed by the peerage. And the inverse was true, too. If you were tired of being the proper lady all day long, you could let your hair down and play dead, as in the gory Blue Beard Tableau illusion (of which more later).

The Dutch historian Johan Huizinga argued in the late 1930s that we transmit culture through play. Not through the professionalised forms of theatre or sport that represent themselves self-consciously as cultural icons, but through simple fun and games. For Huizinga, play ‘promotes the formation of social groupings’ that last long after the end of the game, whether it’s a card game, amateur sports or children’s make-believe. When we forward a zany video to our contacts or imitate dance moves found online, we bind virtual social ties to our real-world friends.

In his book Homo Ludens (1938), Huizinga describes play as a ‘magic circle’ that creates a lasting ‘feeling of being “apart together” in an exceptional situation, of sharing something important, of mutually withdrawing from the rest of the world and rejecting the usual norms…’ What better way to describe the urgency with which we turned to internet videos since March 2020?

Parlour theatricals helped 19th-century people try on emotions and get to know other social worlds from the inside. Characters ranged from conmen to colonels, doting mothers to drunken fathers. Authors in the 19th century praised amateur theatricals for their ability to teach ‘a certain knowledge of the emotions and passions of humanity, which can rarely be acquired elsewhere.’ Instagram Reels videos update this panoply for the 2020s in the one-person show genre. Laura Whaley, a Canadian content producer, enacts dozens of workplace archetypes, such as the gossip, the overachiever and the girl boss, all using quick cuts and minimal costume changes.

Whaley films herself in three-quarter view, wearing a headset and microphone, staring at a computer monitor. In June 2021, Whaley-the-boss announces that the office will be reopening after coronavirus restrictions ease. Whaley speeds through the gamut of responses in five different characters: a woman wearing a bathrobe complains that she doesn’t have any office clothes, nor the ability to control her facial expressions. Whaley-the-suck-up, in a pink power suit, exclaims: ‘On my way!’ Whaley is easily recognisable in each of these roles. Sometimes she changes only her glasses. But it’s precisely the incompleteness of her costuming and props that draws in viewers. Not only is the sense of ‘making do’ familiar from the limitations of lockdown, but by recognising Whaley’s characters from our own workplace dramatis personae, we participate in the play.

Contemporary makeup tutorials paint the magic circle of play directly on the body. In short, first-person videos, creators demonstrate makeup techniques using their own face as the canvas. Even as creators pull back the curtain, explaining how to create illusions using makeup, the metamorphoses are profound.

The genre also recalls a popular 19th-century parlour game: the tableau vivant. Using simple props, costumes and lighting effects, guests acted out famous paintings in their living rooms. Guidebooks recommended tableaux as the easiest theatrical entertainments, since they didn’t require spoken dialogue or movement. Their most crucial element was a layer of gauze hung between actors and audience. This real-world filter seemed to flatten the three-dimensional space like a painting. In Edith Wharton’s novel The House of Mirth (1905), the tragic heroine Lily Bart achieves her greatest social triumph performing as Mrs Lloyd in the 18th-century portrait by Joshua Reynolds. Wharton notes that the illusion of a tableau depends as much on the audience’s receptiveness as on the actors’ talent. It’s the strange interplay between life and stillness that provides, as she writes, ‘magic glimpses of the boundary world between fact and imagination’. This is Huizinga’s ‘magic circle’, which viewers can step into and out of at will.

Even for an audience accustomed to digital filters, the transformations shown on video are hard to believe – and harder still to confirm without repeated viewings. The most playful of these videos are the ‘makeup illusions’, in which creators draw eyes on their eyelids or invert their faces by painting lips on their foreheads.

Bodily transformation, especially grotesques, take on new meaning in times of social uncertainty. In medieval folklore, vampires expressed a fear of contagion that breached the limits of the body. Diseases of the 19th-century city, such as tuberculosis, caused wasting and wanness, not unlike the purported results of a vampire’s bite. Decapitated heads and other monstrous effects figured strongly in 19th-century home entertainment manuals. These grotesque amusements took on slightly different forms across publications, but the staging technique was always the same. For example, ‘The Severed Head’ from What Shall We Do Tonight? Or Social Amusements for Evening Parties (1873) produced a single head that stuck out from beneath a tablecloth. Guests were meant to stumble upon it, horror-struck.

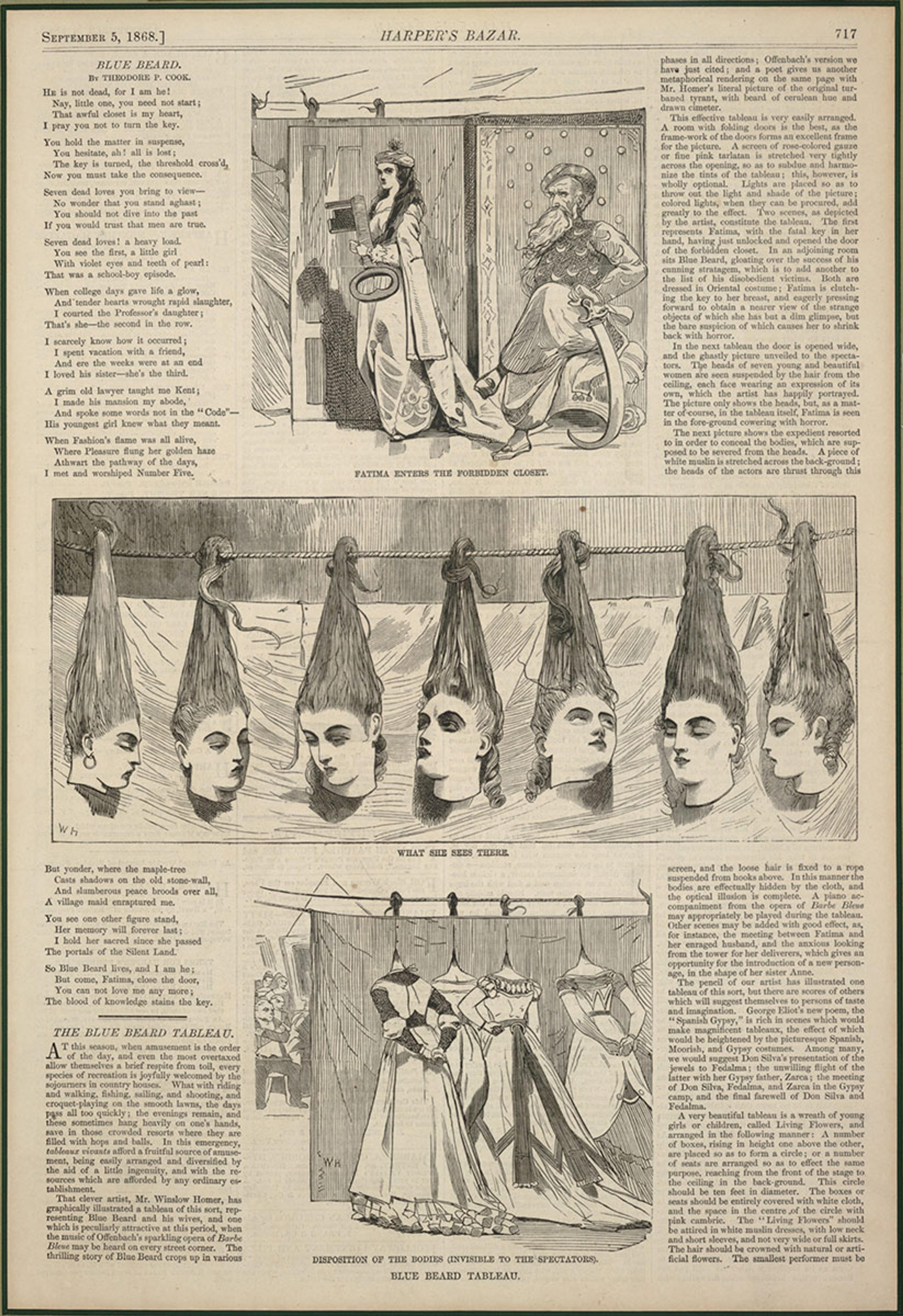

‘Blue Beard Tableau’ from Harper’s Bazaar, 5 September 1868, by Winslow Homer. Courtesy the Smithsonian Museum of American Art

Winslow Homer’s aformentioned ‘Blue Beard Tableau’, which appeared in Harper’s Bazaar in 1868, invited ‘mannered’ women to embody the murdered wives from the French folktale by poking their heads through holes in a sheet, tying their braids to a suspended rope, and maintaining a closed-eyed, slack-jawed expression.

In Laboring to Play (2005), the scholar Melanie Dawson describes these Victorian-era amusement manuals as ‘visions that extended beyond the comfortable circumference of everyday life to celebrate displays of exaggerated, unsocial bodies.’ As we continue to Zoom in to work meetings and birthday parties, wrapped up and distorted into those infinite amorphous and lumpy shapes that all throw-blankets create, we’re inventing new displays of the unsocial body – not beyond the comforts of the couch, but produced in situ.

One such display emerged on social media from the darkness of the pandemic, stiff and with arms crossed, one might imagine. In an article from the British Dental Journal, the dentist Suzy Harkness in Belfast describes in horror a 15-year-old boy’s emergency room treatment to remove the melted plastic stuck to his upper row of teeth. He had boiled white thermoplastic to mould into vampiric canines so that he could temporarily participate in #vampirefangs, the viral TikTok challenge of 2020. For this, people posted videos showcasing their ghoulish homemade prosthetics and provided instruction on how to affix press-on nails to their teeth. It wasn’t long before a new round of videos showed teens tugging at their fake fangs with regret. The plastic had cooled and set a white amorphous blob across the young boy’s smile. Harkness sent a warning to the dental community: ‘The ultimate challenge in the management of social media is to maximise its benefits and minimise its risks.’

Part of the appeal of watching young people at play may lie in their blissful disregard for the consequences, especially when dangerous or socially threatening play escapes the boundaries of make-believe and crosses into the real world. What benefits might young TikTokers get from play that potentially disfigures the body permanently? Kids in the West once turned to body modification to literally counter culture (consider punks’ safety-pin earrings and mohawk hairstyles). But does something else pull at us when watching those desperate tugs at acrylic nails affixed to teeth? The contemporary grotesque is not just form but also feeling. We sense that the pandemic has made monsters of us all.

Young TikTokers are famous for combining bad acting with acting badly. In September 2021, the ‘Devious Lick’ challenge swept through the halls of TikTok. Videos of students vandalising school property, stealing supplies and pulling pranks on teachers trended on the app as much as they did on network news cycles reporting adult shock and outrage. As students returned to in-person instruction after a year of home education, so too did the thrills and amusement of misbehaviour. The pranks made visible the social turmoil that was so desperately masked by school administrators who promised a return to a ‘normal’ school year, despite the exceptional circumstances.

The overturned school environment was also an attractive play-setting in many Victorian parlour theatricals. For example, in Tony Denier’s Parlor Tableaux; or Animated Pictures (1868), amateur actors are instructed to stage ‘School in an Uproar’, depicting ‘the uproar in a village school the moment the boys think that the schoolmaster has gone out for a long time’. Set against ‘lively music’, the still scene depicts a number of boys tossing books around the room, drawing rude pictures of the schoolmaster on a wall, and engaging in a violent brawl over an apple. Similarly, ‘Mischief in School’ from The Sociable (1858) stages an audience of three to four boys watching their peers sketch out a ridiculous caricature of the master.

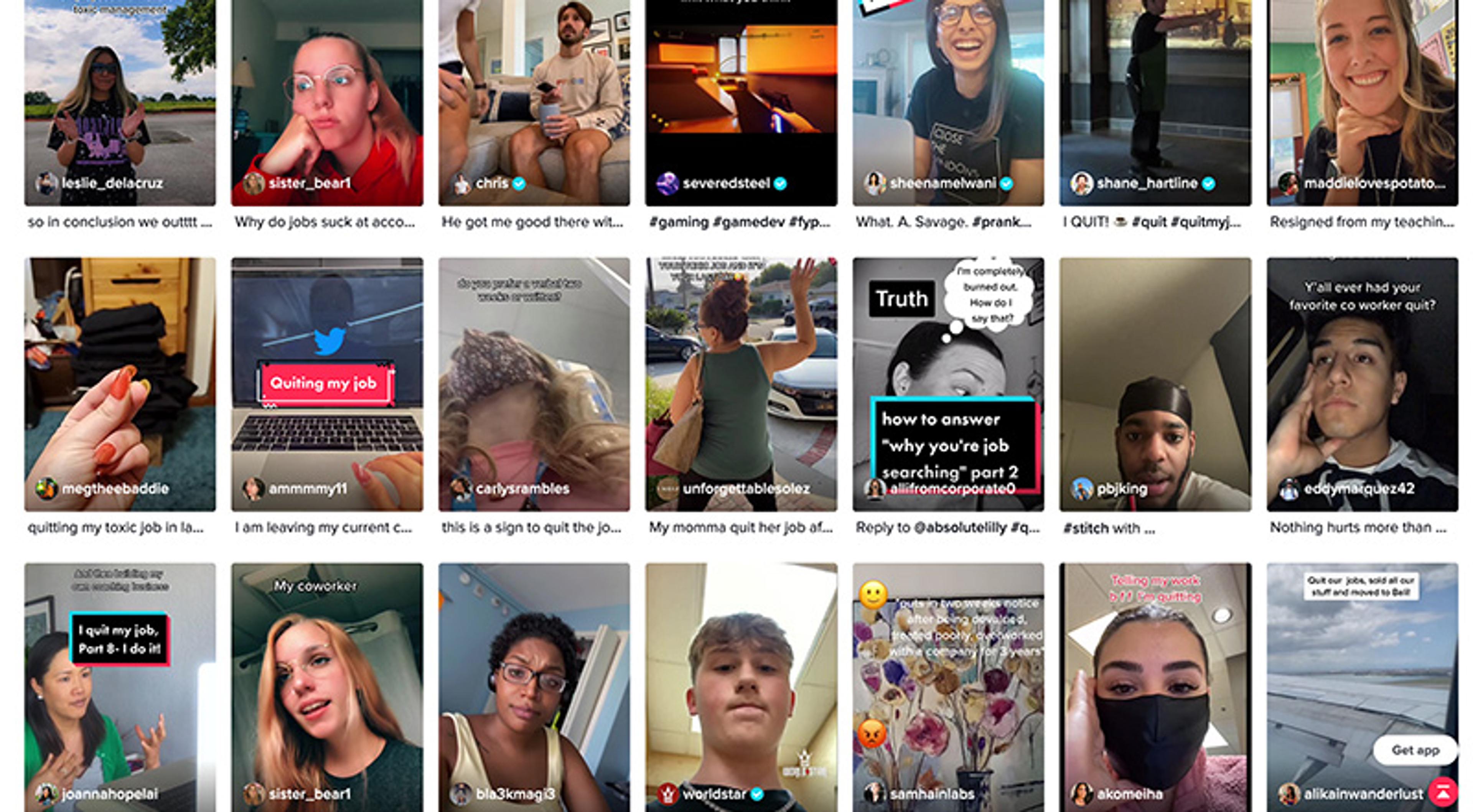

#quitmyjob. Courtesy of TikTok

Adolescents are hardly alone in their resistance to returning to in-person activities. From university campuses to corporate offices, many working adults quit their jobs, filmed their exits, and posted them to TikTok under #quitmyjob. With a little choreography and playful post-production, TikTokers collectively staged what some management researchers have described as ‘The Great Resignation’ – final acts fuelled by long-withheld dreams.

Play is liberating because it can transform the most familiar circumstances into fantasies. It is challenging for the same reason. The mise en scène of the Victorian parlour used curtains and candlelight to signal a space designed for play. TikTok and Instagram Reels accomplish this transformation with stunning immediacy and few physical props. Look down at the screen and you’re in the world. Look up and you’re out – on a busy street or at the dinner table in the middle of a conversation. Sometimes, it’s hard to keep track of which rules we’re playing by. Like changing social-distancing guidelines and masking rules, social amusements demand rapid adaptation. We’ve all been reduced to amateur players during the COVID-19 pandemic, struggling to learn our roles. Our challenge is in learning where to draw the magic circle.