I struggled to piece together what had happened, catching only fragments. I saw my brother, Dave – 8 inches taller and more than 100 pounds heavier than me – coming at me. Then another flicker: hitting the wall behind me. He must have shoved me. I can’t remember if I fought back but, if I did, it didn’t matter. The next thing I knew, I was on the floor, half in the cat’s litterbox, with Dave towering over me. I had wet myself.

I sat rocking on the bed, crying and holding my cat as I thought about how much I’d hoped his visit might be different. Dave had come to Florida to help clear out the house and reminisce as we grieved the suicide of our paraplegic brother Chris.

As I sat there in the house where Chris died, my mind drifted to better times. We lived on a big hill, and my brothers (who grew up together a decade before I was born) would send me flying down it on snow saucers in the winter and in a little wagon in the summer. I was like their little crash test dummy, and I couldn’t get enough of it. They were my two favourite people in the world.

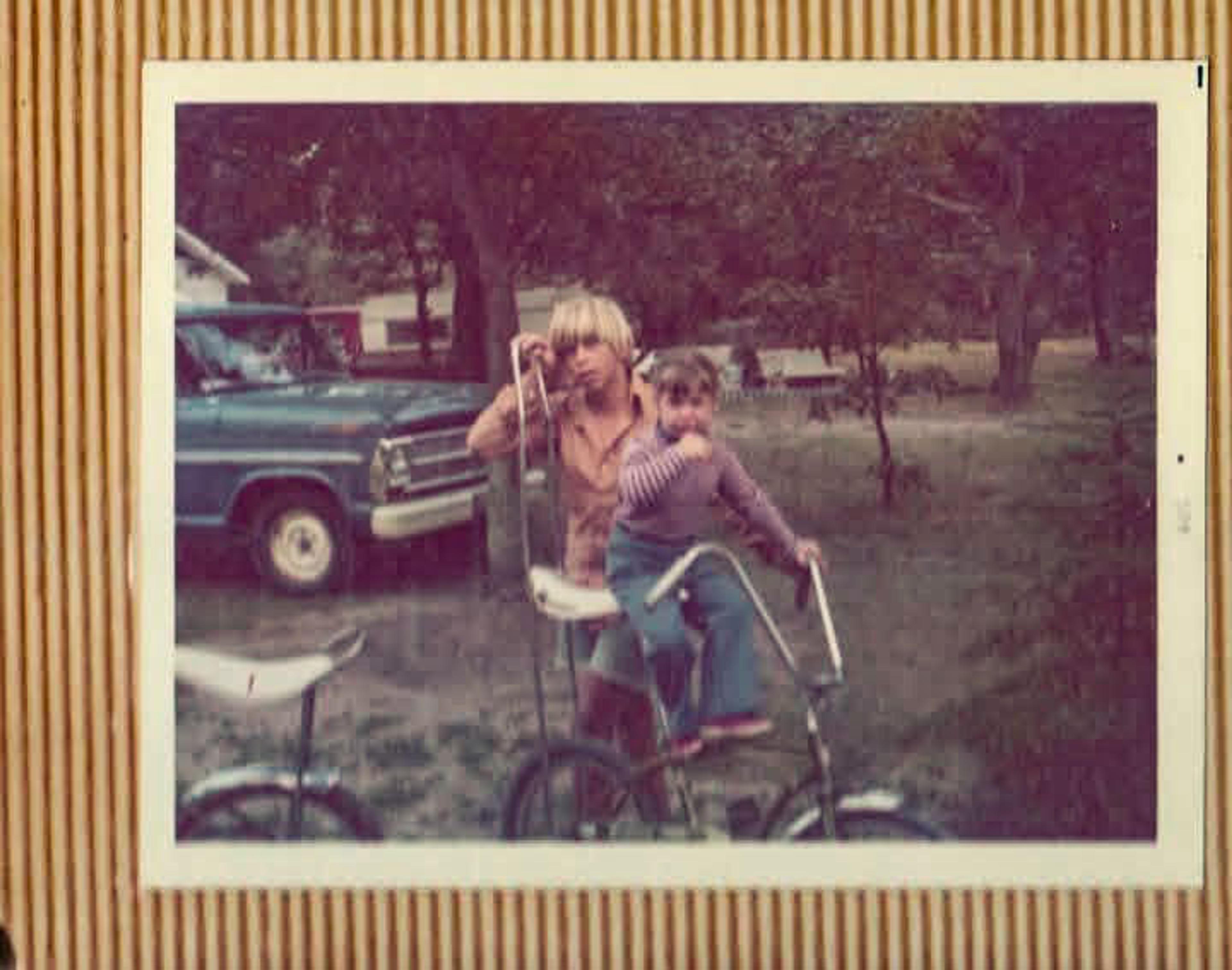

The author with her brother Chris teaching her to ride a bike, c1973

When Dave was 17, he kicked Mom across a room and into a wall. He was immediately sent to live in an apartment 5 miles from our house. Chris left less than a year later, choosing the open road and a fast new motorcycle. I was six when they left, and all I dreamed of was having my brothers back. A year later, it felt like fate had smiled on me when Chris returned after a motorcycle crash to relearn how to live his life as a paraplegic. For show and tell, I told my second-grade class about my brother’s accident and how he’d probably never walk again, and doing wheelies in his wheelchair as if it were a bragging point.

Eventually, Chris became independent and moved to an apartment, leaving me alone again with my mother’s angry moods. At 16, I ran away, reluctantly returned to finish high school, and then finally escaped for good to nursing school. I didn’t want to be a nurse, but I needed a stable income to be permanently free from that house. Even then, I could see how I was beginning to adopt my mother’s volatility.

I was angry with her for so long for not getting control over her moods before birthing us into the middle of them. As an adult, my opinion of her softened when Mom told me about her uncle. He wouldn’t keep his hands off her and her sisters. Her mother, whom I never met, scolded her when my mother tried to seek protection. ‘Don’t you tell such lies. Now go get ready for church.’

She married my father at 16, and had Dave and Chris before she turned 21. Marrying was a young girl’s only real option in 1956, she said. She laughed about having to learn to cook for five, but never talked about mastering any coping skills. Neither did I; it never occurred to us or anyone else. She routinely managed her emotions by throwing things, yelling, and occasionally hitting someone. The worst was when she would serve up silent treatments that could last several weeks. My poor Dad didn’t have any idea what he’d married into, but he learned to stay out of her way.

From left to right: the author, Chris, her mother, Dave and her father, c1986

I wasn’t surprised when Mom told me she wasn’t going to treat her cancer. She told me: ‘Life isn’t that great, and I’ve done my work here.’ She died the day after my 27th birthday. She’d earned a master’s degree in special education, raised three children, and single-handedly guided Chris into his new life on wheels while holding our family together as best she knew how.

Maybe it made sense that I’d wind up here, picking myself up out of cat litter. I measured the windows of Chris’s place so I could reinforce them and keep Dave out. The next day, I replaced all the locks.

Five months earlier, in May 2020, a new virus was killing people, shattering my plans for my 50th birthday – a whole year in Colombia learning Spanish. But, as a seasoned ER nurse, I thought I should at least do my part since I was trapped here, in the States. I was about to start a travel nursing assignment when words tumbled out of the phone and delivered my new reality: ‘Florida’, ‘Chris’, ‘gun’. The message snapped together in my head. Chris had been found dead in his home with one of his guns in his hand.

‘You left me alone with DAVE?’ I screamed at the ceiling. I couldn’t talk for nearly two days. My thoughts wouldn’t stand still, and the nightmares began that night.

Somehow, I showed up to work. I pulled the same dirty mask out of a dirty paper lunch bag and wore it repeatedly. The heavy doors to patient rooms were kept closed, so I couldn’t hear the monitors. I expected to enter each room to discover a monitor blaring over a dead patient. I put people on life support, and many never walked out. Leaving work, I worried I was carrying a deadly virus on my clothes or in my hair.

After cleaning the bloody room, I couldn’t return to patient care

After a month of tripping over bodies and running from unseen monsters in my dreams, I left work to clean the room where Chris had died. There, I learned that a bed full of dried blood resembles a candy apple, crisp, shiny, red and smooth. I learned that paramedics and police don’t clean up behind themselves. Medical examiners lose track of bodies. Funeral directors hit on grieving women paying cremation bills.

The responsibility fell on me, just as it had when our father died 10 years earlier. Dave, who would later bloody his then-wife and spend a year in prison for assault and battery, was not reliable or trustworthy, so I was listed as the executrix for Dad and, now, for Chris. He trusted me, alone, to split everything with Dave 50/50.

After cleaning the bloody room, I couldn’t return to patient care. I spent the rest of that summer trying to outrun myself on a bicycle in Maine. Then, winter looming, I drove back to Florida and lived in Chris’s house to begin the rest of the business that follows a death, including this visit from Dave.

I tried to distract myself with a local nursing job, but the Delta wave of COVID-19 struck, and patients in Florida argued with me, called me a liar, and sometimes spat at me. COVID is just a hoax, they’d gasp, as I helped fit a mask over their face to assist their breathing. Hell, even Chris fought with me over the ‘hoax’ of COVID a month before he killed himself. Hoax or not, the next stage for these people after that mask would be life support and maybe death. In my raw state, I began to think that letting them die might feel better than fighting for them. The thought frightened me.

I quit ER nursing forever and sought therapy. The only therapist available had just lost her husband and was in tears before the end of our second session. I didn’t go back. I didn’t have insurance anyway.

The day after the assault, with Dave gone, and after securing the house and changing the locks, I took stock of the bruises, the sore throat, and the pain that accompanied each breath. I could see the imprint of Dave’s huge skull rings in the emerging bruises on my torso. The bruises on my neck told the rest of the story: he had choked me until I passed out. No wonder I forgot. I took photos of my bruises, but I still couldn’t remember the attack or the minutes leading up to it.

I added cameras to monitor the Florida house and took a nursing assignment three hours away in a new type of virtual hospital programme, where I didn’t need to be in the same room with patients. Several weeks later, I still couldn’t breathe without severe pain. The X-rays showed nothing broken, but a nurse thrust the number of a safe house into my hand.

Untitled 1 © Anita Lambert

Sleepless nights, interwoven with nightmares, blended into uneasy days, interwoven with fear. Dave’s threats came through voice messages, texts and emails: ‘I should have finished the job.’ ‘I have guns, you know.’ ‘This is all your fault, you little bitch.’

I have never been more scared in my life than walking out of that courthouse

I remained constantly on alert. After speaking with two of Dave’s estranged adult daughters, I realised they needed to see a woman do more than hide. I filed a complaint with the court, and I hid while waiting for the day I would ask a judge for court-ordered protection from Dave. I printed his emails, text messages and the photos of my bruises with snapshots that showed his rings.

On days off, I drove the three hours back to Chris’s house. Clearing it out took two months. At one point, Dave did come back. He vandalised the house, took everything from the garage, kicked over a gallon of milk, and urinated in the corner. Finally, he drove away in Chris’s beloved car. I watched what little I could see on video from the other side of the state. Later, I sent him the car title.

Finally, I sold the house.

Dave didn’t show up in court, and I was awarded a lifetime order of protection. I have never been more scared in my life than walking out of that courthouse. A piece of paper couldn’t keep my brother from coming after me and, at that moment, he knew my exact location.

Shortly after, I boarded a flight from another state to Bonaire in the Caribbean with my suitcases and my cat. I managed a property on this Dutch island, safe in knowing that felons aren’t awarded passports. I joined a group of Sibling Suicide Survivors online. I read thoughts there that echoed my own.

Eventually, I returned to the US and moved to Oregon to learn a new field of nursing. Every six months, I would move to a new area, go to the local police station, introduce myself, and hand them a copy of my order of protection, with the photos and messages. I practised escaping out of windows and through backyards with my cat and my go-bag from a dead sleep, collecting spare keys I’d hidden en route. I never communicated with Dave again, but his threats still came.

In November 2024, I learned that Dave had died of alcohol-related problems. By then, I’d quit nursing, finding patient care too suffocating. I continued with the support group and, with the triggers of violence, blood and tragedy less vivid, began to miss Chris.

Untitled 2 © Anita Lambert

With the fear gone, I realised that I didn’t blame Dave or my mom. We were all running from things we couldn’t control. More than anything, I’m sad for what we each became and angry at the overbearing invisible weight we were all forced to carry.

I still watch over my shoulder. I still miss Chris. I still can’t remember all the events of that night in Florida.

I take painting classes now, and write a lot, and try to learn how to carry the weight. Sometimes I just sit and cry, and that’s OK. Grief is persistent; we’ll always be without whatever it is we grieve. We can’t erase trauma, and sometimes other people’s trauma bleeds into our own. Grief and trauma demand attention. If I don’t give it, they’ll take it without my consent, which is too much like how we got here to begin with.