On a wet spring day in 2018, I stood outside my house in the Sierra Nevada foothills in California and called my mother-in-law. ‘I can’t take care of him alone anymore,’ I said, my voice breaking. ‘I need you guys to take him for a while.’

Inside, my husband of 10 years was weeping and pacing from one end of the timber-framed cabin to the other, his linen shirt soaked in sweat. Over the past few years, he’d had so many nervous breakdowns I’d lost track of where one ended and the next one began. He quivered and shook, ranted and wailed, talked for hours, couldn’t be alone. Night after night, I’d stayed up with him until dawn; I could feel my own bones cracking under the weight of his seemingly bottomless pain.

‘There’s a train to Fremont at 2 pm,’ I said. ‘If I can get him on board, can you pick him up at 7?’

At the Amtrak station, I watched as the conductor questioned my husband. I feared he wouldn’t let him on the train, unkempt as he was, a leather satchel slung over his shoulder packed with a laptop, essential oils, incense and a framed photograph of the raga singer Pandit Pran Nath. Please, I begged silently. Then my husband stepped on board, and the door slid shut behind him. I texted my mother-in-law that he was on his way.

My husband and I had moved to our off-grid homestead just a few months before. The area was overdue for a devastating wildfire, a fact that had only become clear to me after I’d fallen in love with the sparkling river, the fawns and black bears, and the narrow dirt road no fire truck could ever drive down. But, instead of being cowed by the danger, I’d vowed to educate myself about the best ways to manage it. I would learn to use a chainsaw. Prepare our go-bags. Create defensible space, just like they showed in the FireSafe brochures. I would make our homestead safe – steep slope, dead-end road, flammable wood siding and all.

My husband’s latest mental health emergency had pushed these good intentions to the back-burner. I spent my time driving him to the rural health clinic, arguing with the insurance company, and running him hot baths. I did the cooking and shopping, brought our struggling car to the mechanic, and kept the woodstove going, all while the grass grew tall and the trees went unpruned.

I wanted them to see, in those piles of pine and manzanita branches, how much I loved the land

Now that my husband was at his parents’ house, I applied myself to the fire-proofing project with the same intensity that I’d applied to caring for him. I roamed the hillside with a chainsaw, thinking, That branch and Those saplings and Those manzanita bushes too. There was no ambiguity. And never any question whether my labour was having an effect – unlike the labour of caring for my husband, which seemed to have no clear or quantifiable result.

The limbs I cut, I stacked into piles six or seven feet high. When friends came over, I pointed out the brush piles. I wanted them to understand that I had done this. I wanted them to see, in those piles of pine and manzanita branches, how much I loved the land: so much that I would devote everything I had to ensuring the fire never came.

When I tried to tell my husband about fire-proofing our land, he couldn’t quite hear me: his anxiety demanded his full attention. When we spoke on the phone, I mostly listened to his reports. He told me he was making his bed in the mornings. He was playing video games to keep from thinking too much. He was thinking he could buy an RV and live in his parents’ driveway for a while. Maybe I could live in the RV too.

When I took the train south to the Bay Area to visit him, he wanted to be held while he cried, and he wanted help making decisions. Should he come back to the homestead, or stay at his parents’ house? Should he trust that this was a spiritual experience, or accept that he had a disease?

If he wanted to put out the fire, why was I the only one picking up a chainsaw and clearing the brush?

I did my best to comfort him, but it was like trying to run too soon after a knee injury: my empathy was all worn out. I desperately needed someone to care about how I was doing – but as we bounced from emergency to emergency, it seemed like there was no time to process my own trauma. Although I loved my husband dearly – his brilliant mind and bushy beard, the elaborate soups he’d cook late at night while our favourite sitar record played in the background – I was frustrated by his refusal to stick with therapy, medication or other supports for more than a few months at a time, and only after lengthy coaxing by me. It felt like, the moment anything started working, he’d stop doing it – and all the effort I’d put in to convince him to try it in the first place was for nothing.

Now, when he cried, my distress was mixed with a growing indignation. I’m on fire! he kept saying. Help me! But if he really wanted to put out the fire, why was I the only one picking up a chainsaw and clearing the brush?

Spring gave way to a dry, hot summer. My husband decided to stay in the Bay Area for at least a couple more months. With him gone, I found that I could think, plan and execute tasks, my own needs no longer drowned out by the deafening siren of his distress.

Whenever I heard the chop of helicopter propellors, I’d run to my laptop to check the local news website for fire alerts. Then I’d go outside and pace around, plucking stray pine needles out of the gutters, until the helicopters receded into the distance.

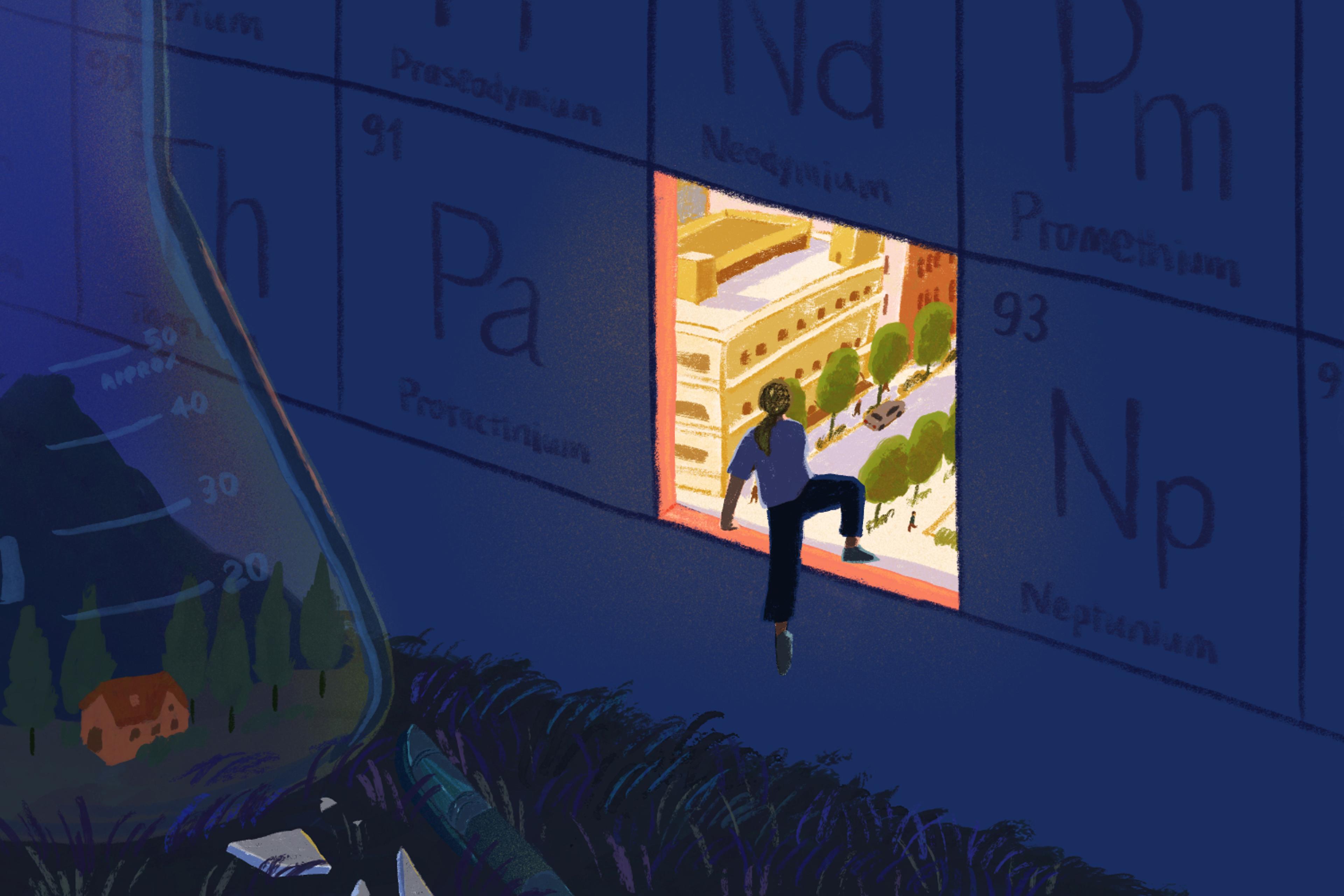

One afternoon, I came across a job posting online. It wasn’t a glamorous position – registrar at a small private college – but that wasn’t the point. Throughout the years my husband and I had been together, I’d worked remotely as a freelance writer, my flexible schedule making it all too easy to drop everything when he needed me. An in-person job would force me to break this pattern. Maybe, I thought, if I could remember how to be something other than a caregiver, he would remember how to be something other than a patient.

The next day, the helicopters kept coming, flying unnervingly low to the ground. A quick call to my neighbour confirmed the queasy feeling in my stomach: a fire had broken out a few miles away.

I grabbed a hose and climbed onto the roof, then I began to spray down the shingles and siding. Fear turned my legs to jelly, and my arms became slick with sweat from the heavy canvas jacket I’d thrown on to protect myself from flying embers. It’s finally happening, I thought. The big one.

I’d been telling myself that my efforts were holding the world together

I looked up, and the beauty of our land assaulted me – the huge pine standing guard near the driveway, the California poppies not yet shrivelled up and blown away. There it was: everything I loved and stood to lose. Everything I couldn’t protect, even if I spent every waking moment prowling the hill with my saw.

My grip on the hose slackened. All along, I’d been telling myself that my efforts were holding the world together, that I was the one thing keeping wildfire at bay, just as I was the one thing that stood between my husband and suicide. This grandiose vision of myself had kept me going through the unrelenting fear, the exhaustion and despair. It justified every sacrifice and silenced every dissenting voice.

Standing on the roof in the midst of a fire alert, I now saw that I could give, give, give to the very last drop of my being, and it might still not be enough. The fire could still burn. My husband could still suffer. I couldn’t save his life for him, any more than I could digest his food or walk around inside his body. As the deafening chop of the propellers filled my ears, I realised that trying to fight his fires was turning my own life to ash.

The heat radiating off the shingles was making me dizzy. More helicopters were coming now, dragging huge buckets of water through the sky. I realised I had better get off the roof before I fainted, so I staggered to the ladder and scrambled down.

Inside the house, the phone was ringing. It was my neighbour, letting me know the fire had been contained. I slipped off my jacket, feeling foolish. The water I’d sprayed was dripping off the roof, leaving streaks on all the windows and sliding glass doors.

I showered, and cried, and ran the well pump to replenish what I’d drained from the tank. Then I went to my computer and applied for the job I’d found.

On the first day at my new position, I felt wracked with anxiety, knowing that, if my husband called me in distress, I wouldn’t be able to pick up – and, if there was another fire, I wouldn’t be there to protect the homestead either. Even though I’d told myself I wanted to break free of my codependence, I hadn’t realised that letting go would be this hard.

When I rushed to check my phone at the end of my shift, there were no desperate voicemails from my husband. When I got home, the cabin was still standing. I was stunned: they had both survived without me for a whole day.

The brush piles I stacked, the hot baths I ran, the phone calls I made – did they make a difference?

My time at that job was shortlived. My husband moved home, only to have another frightening breakdown. At his insistence, we sold the homestead and moved to a tropical island, where he thought the intense sunlight might lift his depression. I was angry. It seemed to me the moment I’d carved out some independence, I was being forced to sacrifice it again. I felt like his mental illness was turning into a trump card: not something we dealt with together as a couple, with as much grace and courage as we could muster, but a threat he could wield to get his way. After two more painful years, I ended the marriage.

I don’t know if my old homestead is still standing, or if my ex-husband found lasting peace from the troubles that plagued him.

The brush piles I stacked, the hot baths I ran, the phone calls I made – did they make a difference? I’ll never be sure. What I do know is that my life began to flourish once I stopped trying to save my marriage and my house, and started tending what I could truly influence and change.