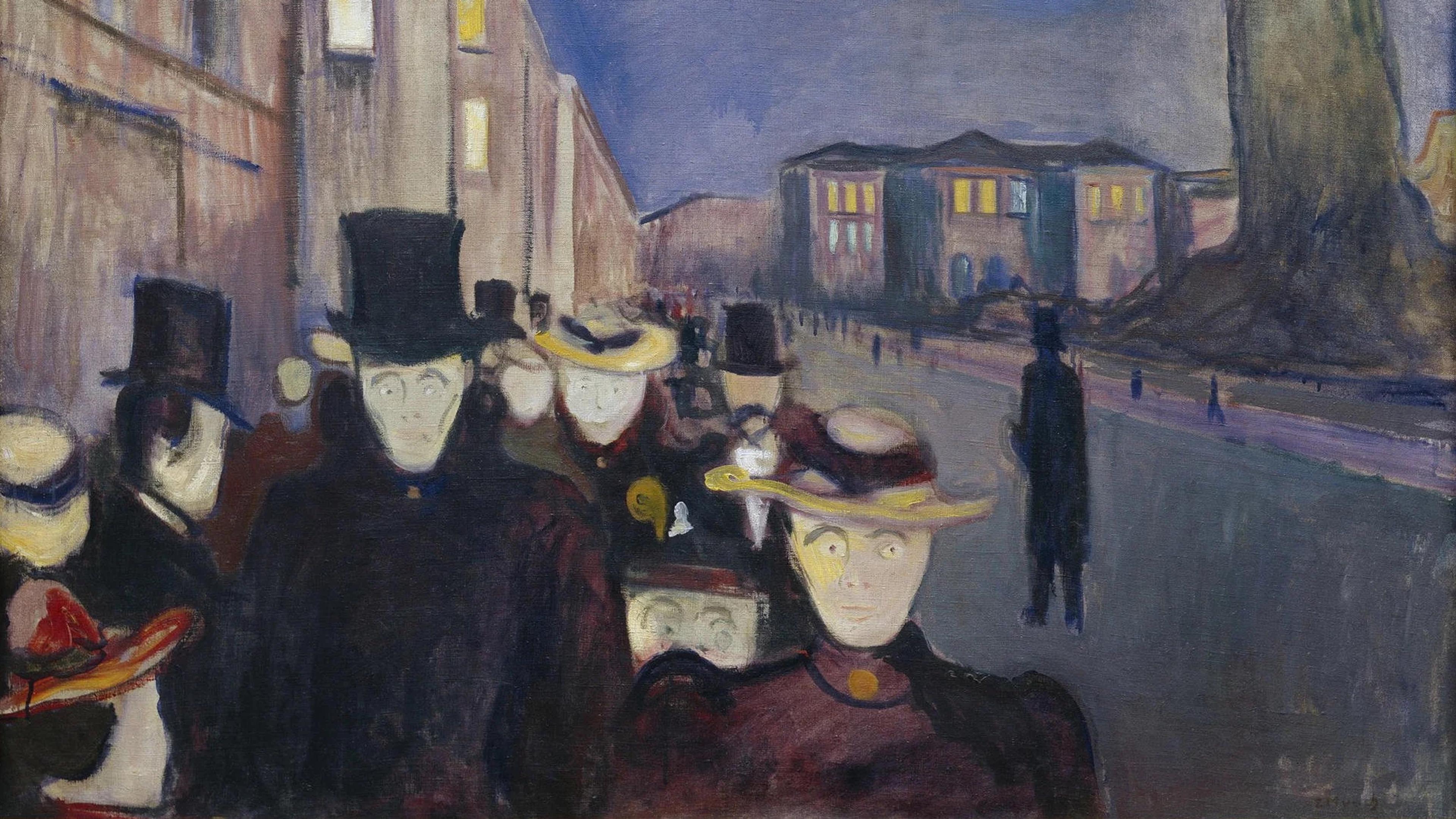

Anxiety is not merely a problem or an affliction for which philosophy offers a solution. Rather, a distinctive form of anxiety, as evinced in philosophical enquiry throughout history, is a fundamental human response to our finitude, mortality and epistemic limitation. Anxiety and philosophy are intimately related because enquiry – the asking of questions, the seeking to dispel uncertainty – is how humans respond to this philosophical anxiety. Aristotle suggested in his Metaphysics that ‘All men by nature desire to know,’ but the enquiring, questioning, philosophical being is, in a crucial dimension, the anxious being. Anxiety then, rather than being a pathology, is an essential human disposition that leads us to enquire into the great, unsolvable mysteries that confront us; to philosophise is to acknowledge a crucial and animating anxiety that drives enquiry onward. The philosophical temperament is a curious and melancholic one, aware of the incompleteness of human knowledge, and the incapacities that constrain our actions and resultant happiness.

Thomas Hobbes suggested, in Leviathan (1651), that anxiety animates curiosity: ‘Anxiety for the future time, disposeth men to enquire into the causes of things.’ We romanticise this enquiry by calling it the love of wisdom, but philosophy itself is an acute expression of our anxiety: ‘I’m anxious, therefore I enquire.’ Our theories of the world, our illuminations of the unknown, are our antidotes to this anxiety. The search for knowledge pushes back the unknown that encroaches, making the world more predictable and, hopefully, making us less anxious. The most fundamental enquiry of all is into our selves; anxiety is the key to this sacred inner chamber, revealing which existential problematic – the ultimate concerns of death, meaning, isolation, freedom – we are most eager to resolve. A crucial component of the theist definition of God is omniscience, from which follows God’s beatific calm: how could a being assured of all-encompassing knowledge be anxious about any eventuality? If we were not ignorant and uncertain, then we would be as gods; but we are not gods, we are anxious humans.

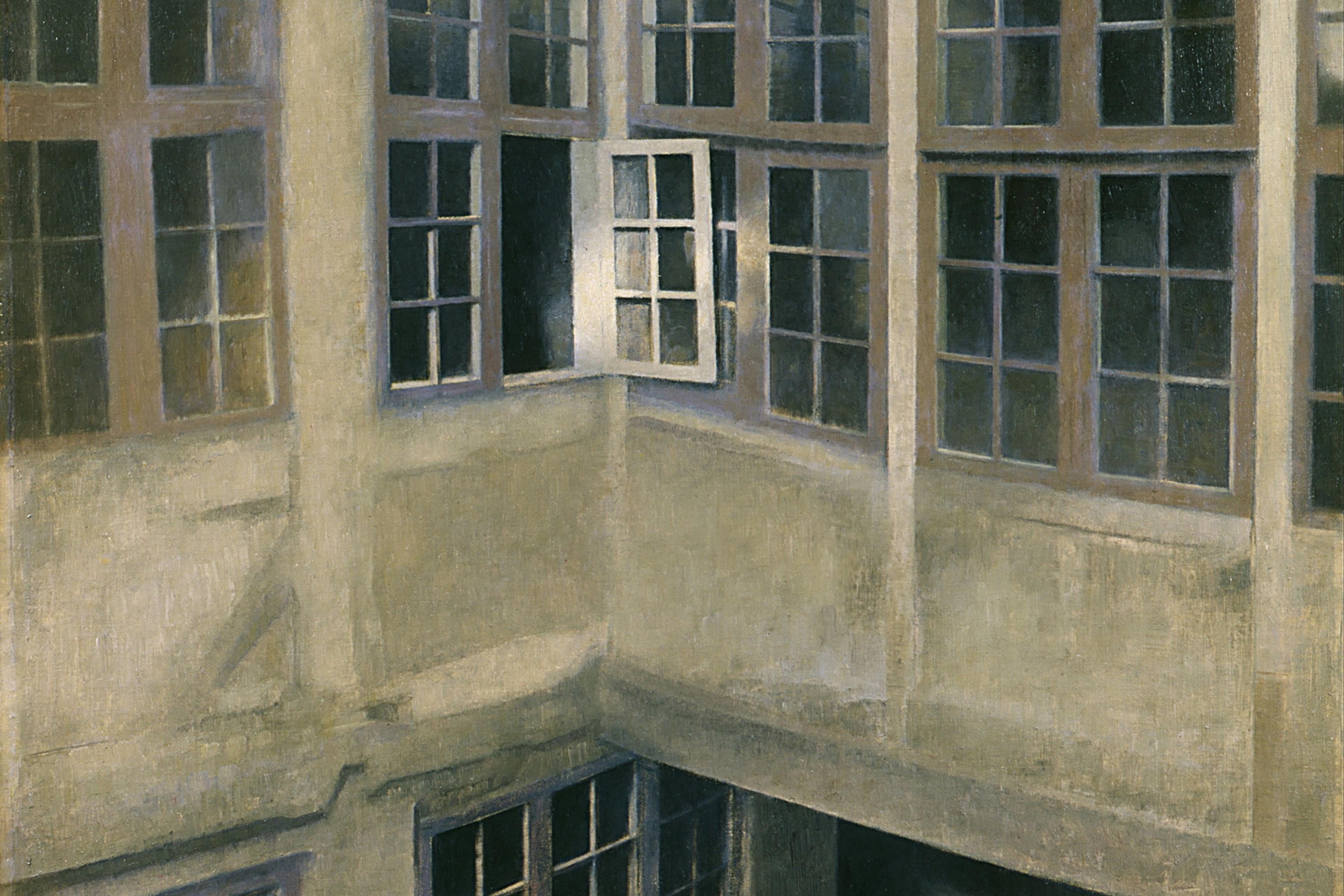

Philosophical enquiry, then, cannot be delinked from its associated anxiety. To ask is to reveal our anxiety about the form and content of the answer. Philosophical anxiety is variegated with epistemic, metaphysical and ethical dimensions: what do we not know? Can we ever be certain? Are there vital truths we will never know? What is the nature of our being? The central epistemic and metaphysical obsessions about the nature of the relationship of the Word to the World – characteristic of Western philosophy – convey a deep unease: are its dimensions amenable to understanding by human thought? Are our minds enclosed in their own worlds, cut off from the proverbial thing-in-itself? The varied theoretical stances that litter the history of philosophy – empiricism, idealism, rationalism – are responses to this epistemic anxiety. Ethical enquiry, too, reveals a deep moral anxiety about our actions, words and thoughts: am I doing the right thing? What is the right way to treat others? What is the right way to live? Will I be rewarded appropriately for my rightful actions?

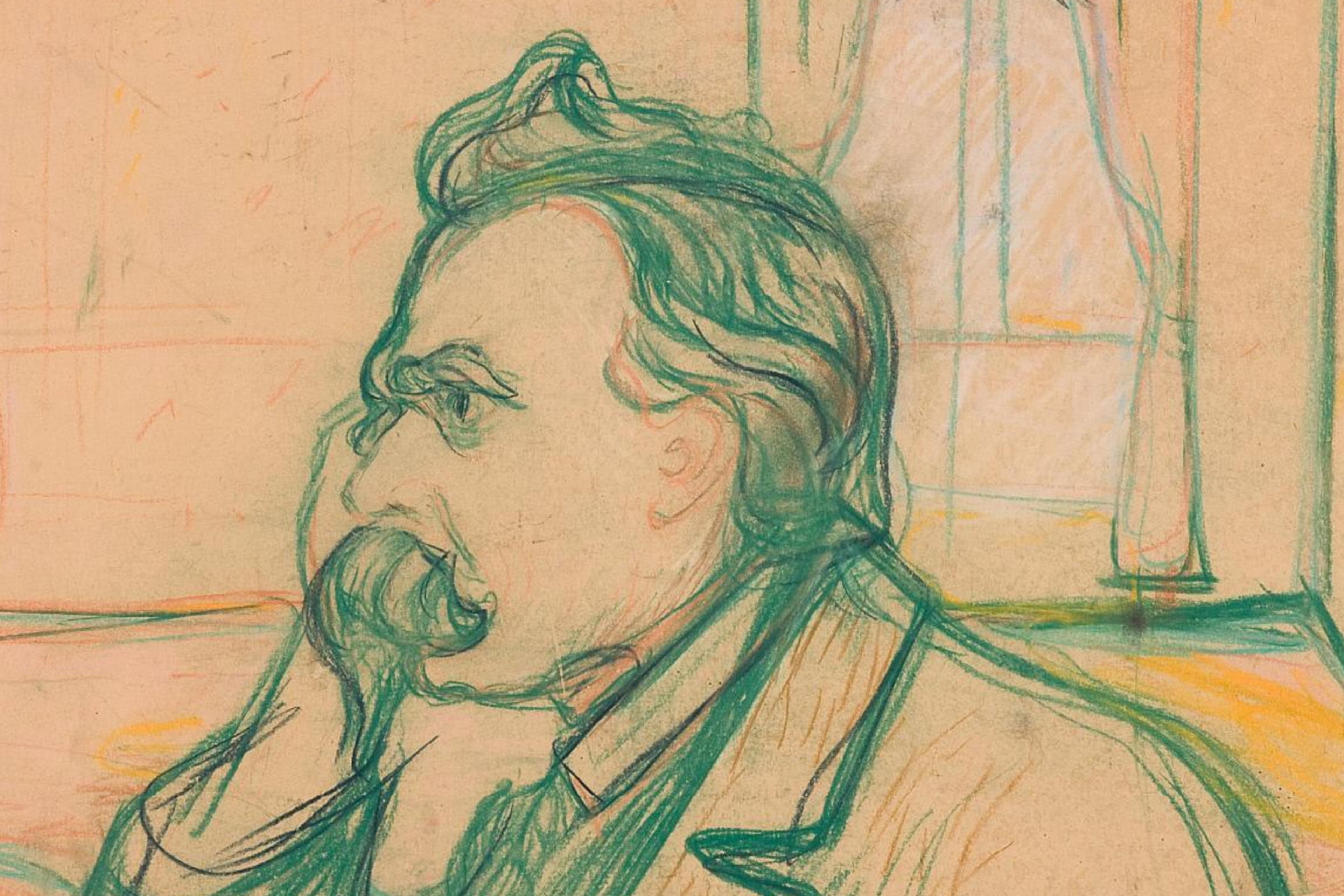

We must ask, as Friedrich Nietzsche, the arch-psychologist, was fond of doing: what emotion and affect underwrites these metaphysical, epistemological and ethical enquiries? The answers, as Nietzsche knew, are psychologically revealing; deep unanswered questions in philosophy carry with them a great anxiety about the possibility of the incorrect answer. Their correctness, and our susceptibility to error, strike deep anxiety into our hearts. We must get this right.

Enquiry by anxiety is clearly evinced in religious thought – as in Blaise Pascal’s Pensées (1670) and Augustine’s Confessions – which displays an acute relationship between faith and uncertainty. It is also found in the idea of existential dread, which is animated by the awareness that traditional, hopeful forms of knowledge have been displaced by newer questions and priorities, as well as in Enlightenment-era valorisations of reason, such as those of René Descartes.

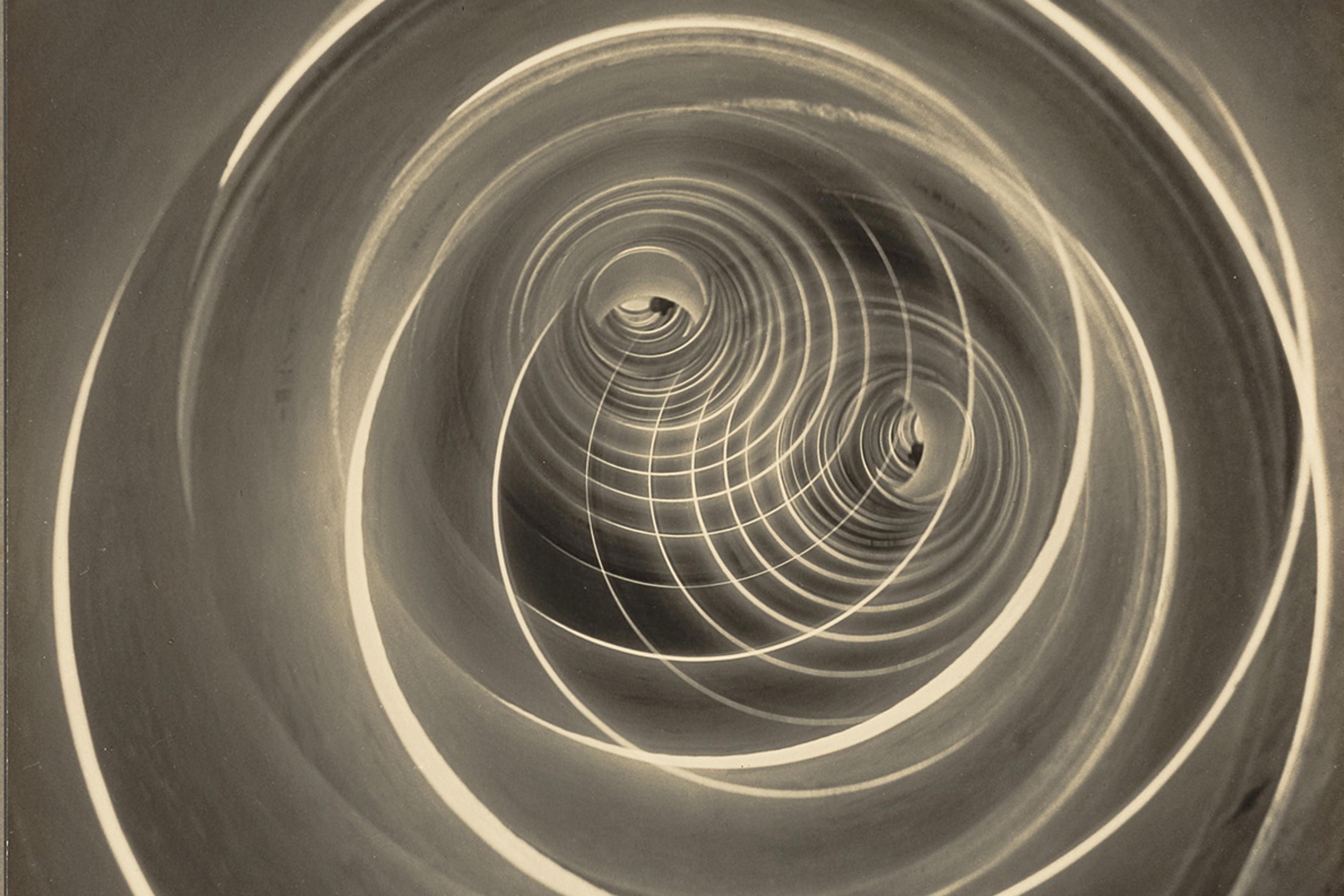

Consider, for instance, his state of mind in the Meditations (1641):

I realise that there is never any reliable way of distinguishing being awake from being asleep. This discovery makes me feel dizzy … I feel like someone who is suddenly dropped into a deep whirlpool that tumbles him around.

The Meditations is overtly psychological in its confessional nature, its frank acknowledgement of the worries that drive Descartes onward, eager to secure a place for reason at humanity’s banquets, a little sinecure free from the Church’s ‘aweful’ reach. To do that, reason must provide a certainty above human frailty and cognitive flaws, revealing, for Descartes, an anxiety generated by the uncertainty of defeasible beliefs: was it possible that we could act and function – morally and politically – all the while being systematically deluded? This drive for certainty, this unwillingness to tolerate error in epistemic assessments, bespeaks a great, terrible worry – a ‘drive for truth’ that Nietzsche accurately described as a human obsession. We must be certain; we cannot tolerate a philosophy that leaves open the possibility that we might be mistaken. Consider, too, an equally anxious, and perhaps more sincere and less affected, self-presentation by David Hume in A Treatise of Human Nature (1739) as he considers the worrying, destabilising consequences of the radically deflationary doctrines he has offered as a challenge to traditional epistemology and metaphysics.

The American pragmatist Charles Sanders Peirce reckoned in his classic article ‘The Fixation of Belief’ (1877) that epistemic doubt was an ‘irritation’, a production of unease. The resultant drive to enquire, to move to a state of belief, possessed a rule for action, urged us onward and upward into elevated realms of thought, possibly looking for grand totalising schemes that would encompass our lived experience. If anxiety, and its related doubts, didn’t possess an acute affective component, it wouldn’t be so richly productive of enquiry. These considerations should force upon us a radical redrawing of the rigid boundaries between the intellectual and emotional: can intellectual query ever be purely rationalist, emotion-free, bereft of personal interest and psychological history?

Further afield, the religious find themselves accepting God’s will or trying to determine its manifestations: the gnawing, persistent worries about redemption, sinning, forgiveness, salvation, are their preserve. The faithful are promised deliverance, but threatened too – depending on the religious tradition – with eternal damnation: what if their assessment of the probability of salvation is incorrect? The religious anxiety about whether faith is sincere enough found profound expression in the intense theological speculation about the relationship between life and reward, between salvation and knowledge. Calvinism, for instance, produced a distinctive, unmitigated terror: am I one of the chosen ones or am I marked as condemned forever? The German theologian Martin Luther described his despair over salvation as caused by his lack of trust in a judgmental God, convinced his grace was blocked by mortal guilt and inhumanly high standards. The simple Pauline claim that ‘He who through faith is righteous shall live’ offered relief through an epistemic therapeutic strategy – all is mystery, but if we consider one mystery resolved by unswerving, committed faith, then all mysteries fall before it.

Implicit in our much-vaunted rationality – which Aristotle considered the distinguishing mark of the human, raising it above the plant and the animal – is anxiety. We are temporal creatures, placed in this vanishing, transient and precarious interval between the past – the domain of regret and mistake – and the future – the domain of anticipation and uncertainty. We modify our present, anxiously, in response to memories and anticipations. Even our most practical definition of rationality has anxiety built into it: will we find the correct fitting of means to ends?

We are thrown into a world awaiting construction and completion by human thought and action, left to fend for ourselves, and the trauma of birth – thrust from the darkness into the light, left to make sense of it all, our primeval anxiety – is visible in our history. We are anxious; we seek relief by enquiring, by asking questions, while not knowing the answers; greater or lesser anxieties might heave into view as a result. As we realise the dimensions of our ultimate concerns, we find our anxiety is irreducible, for our increasing bounties of knowledge – scientific, technical or conceptual – merely bring us greater burdens of uncertainty. As Nietzsche noted in The Birth of Tragedy (1872): ‘as the circle of science grows larger it touches paradox at more places’. The resultant perplexity and anxiety are the inevitable companions of the enquiries we cannot cease from mounting.

Søren Kierkegaard suggested that the most basic human affect, over and above the phenomenal consciousness generated by our senses, is anxiety. The moment we begin to address it by asking What is this feeling? What does it rise in response to? we are philosophising. To cure anxiety, then, might remove all that is distinctively human – an accusation sometimes levelled at Stoicism and Buddhism. We should not expect or demand totalising relief for fear of neutering our affective, enquiring selves. Humans are philosophising animals precisely because we are the anxious animal: not a creature of the present, but regretful about the past and fearful of the future. We philosophise to understand our past, to make our future more comprehensible. The unknown produces a distinctive unease; enquiry and the material and psychic tools it yields provide relief. Where anxiety underwrites enquiry, we claim that the success of the enquiry removes anxiety and is pleasurably anticipated. Enquiry comes to an end when we’re not anxious, but rather sated and blissful. There is no more to be asked, answered or understood; understanding and enlightenment have been achieved. Philosophy is the path that we hope gets us there. Anxiety is our dogged, unpleasant and indispensable companion.

I am deeply grateful to John Tambornino, Bradley Armour-Garb and Justin Steinberg for their very useful comments on an earlier draft of this idea.