Years ago, as a junior academic, I worked late one evening on a project with a tight deadline. While I sat at my desk, a senior colleague asked if I had a moment. Sure, I said. He shared his plans for a research paper and asked for my thoughts. I gave my response. He asked a question. I responded. It went on, back and forth. The light faded outside and the Word document I’d created lay untouched on my computer. I wondered how I could extricate myself from this conversation. And then came my opportunity – he paused and said: ‘I’m sorry, am I keeping you from something?’ I thought, Thank you, yes, I need us to stop talking now – but what actually emerged from my mouth was: ‘No! Not at all!’

More than an hour later, after making no progress on my own work, I left the office feeling annoyed at myself. Surely I should be capable of politely excusing myself from that sort of situation? I thought of all the people I knew – friends, colleagues, characters from fiction – who would have made a better job of protecting their time. There was the colleague whose abrupt ‘I need to get back to work’, awkward as it was, would have facilitated a hasty escape; and the more elegant approach of a friend whose warm but unrelenting ‘This sounds fascinating, good luck!’ would have had things wrapped up quickly. But I couldn’t imagine myself saying those things. I wasn’t that sort of person, and everyone knew it.

I’d be more embarrassed to tell this story if I didn’t know I was in good company. A Google search of ‘How to be more assertive’ returns more than 22 million results. Women have more trouble with assertiveness than men do: a study by the Gender Action Portal at Harvard University found that, in salary negotiations, women concede earlier than men, anticipate greater backlash, and are discouraged by others’ perceptions of assertiveness as a non-feminine trait.

I’m more assertive than I used to be, largely through necessity: I’m a single parent with a full-time job, and fending off demands is a matter of survival. But I’ve changed in another way too. I cut my philosophical teeth on theoretical issues in metaphysics, but increasingly I have little time for philosophy that’s not directly relevant to the issues that ordinary people encounter every day. That’s affected the sort of research I do, and it’s changed what I’m interested in outside of my research, too. After realising that philosophical analysis can help people think through their problems, I started coaching. One strategy that I often use involves applying Aristotle’s philosophy to help people become more assertive.

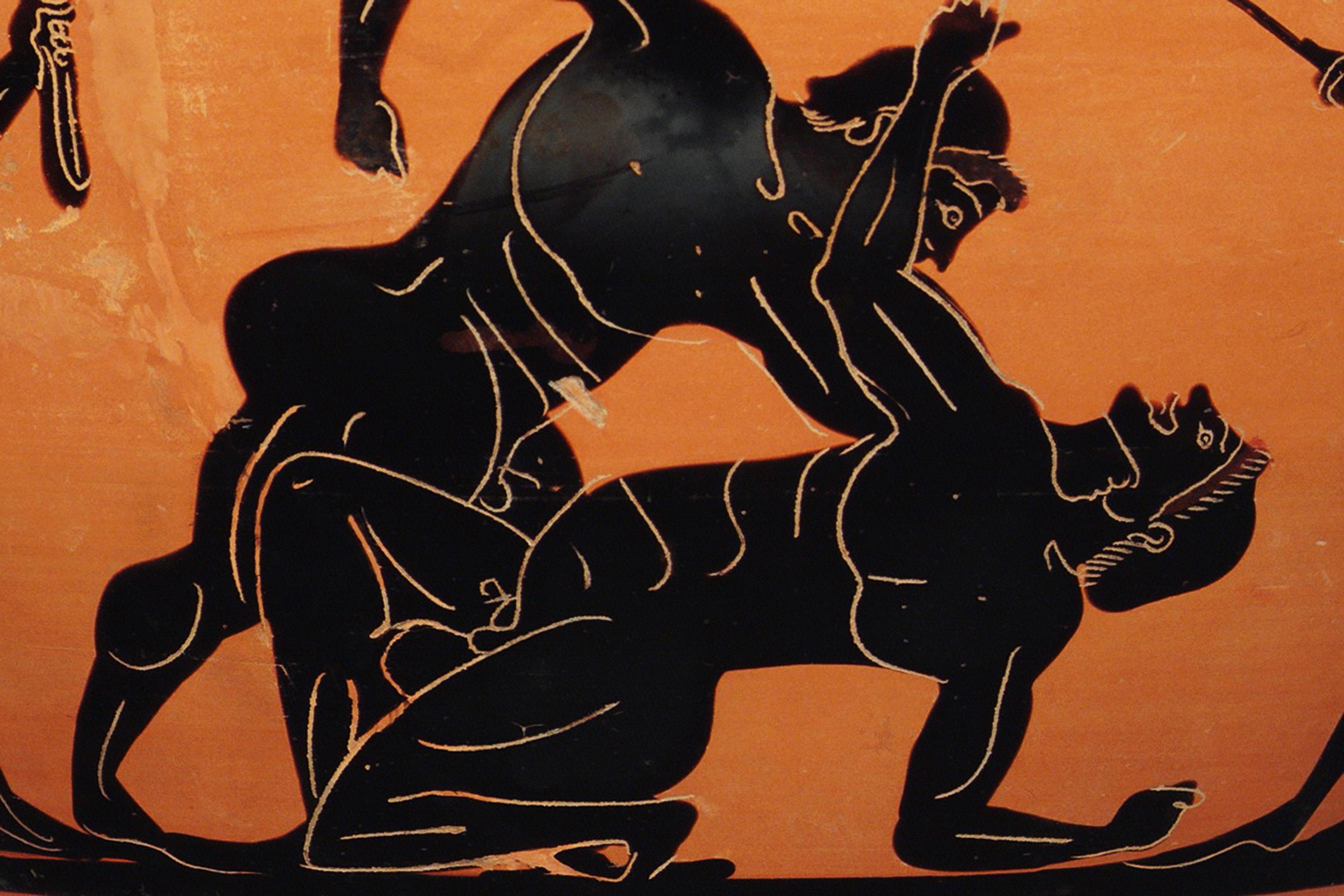

In his Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle was concerned with how to live a good life. A good life for humans requires a virtuous character. Virtues are character traits that exist at the mid-point of a spectrum between two vices. So, tact is a virtue, which we find on a spectrum between the vices of dishonesty and brutal honesty. Courage lies between recklessness and cowardice. Friendliness lies between surliness and obsequiousness. You get the idea. The belief that virtue lies in moderation is not unique to Aristotle, of course; we also find it in Confucianism, Buddhism, and Islam.

Moderation has an intuitive appeal. Kids are quick to grasp that, while telling lies will get them in trouble, sincere remarks about how bad their babysitter smells are also discouraged. However, when it comes to traits that we feel anxious about, we often lose sight of moderation. Anxiety leads to all-or-nothing thinking about assertiveness: we wish we could stand up for ourselves, but we’re afraid that we’ll be arrogant if we do, so our options shrink to a binary choice between ‘walkover’ and ‘arrogant’, and we continue to be too accommodating. All-or-nothing thinking – which psychologists call ‘splitting’ – is a symptom of certain personality disorders. It’s a remnant of how we saw the world as kids, when people were either ‘goodies’ or ‘baddies’. Eventually, we learn to see the nuances between the extremes, but we all lapse into all-or-nothing thinking sometimes. Reminding ourselves that assertiveness, like honesty, exists on a spectrum, and that virtue lies in moderation, is one way in which taking an Aristotelian approach can help us be appropriately assertive.

Moving in the direction of assertiveness is uncomfortable for people who aren’t used to it. How do the overly accommodating among us act assertively without it feeling clunky and awkward? Here, too, Aristotle can help. For him, virtue needs to be learned. We don’t pop out of the womb innately attuned to the right balance between dishonesty and brutal honesty, cowardice and recklessness, surliness and obsequiousness, and so on. We need to develop the right habits, and that comes through practice. Aristotle emphasised the importance of community, education and role models in this process. By surrounding ourselves with virtuous people, following their example, and drawing on their advice and mentorship, we learn to be virtuous. This is a familiar point: generations of parents and teachers worry about children having positive role models; the US entrepreneur and motivational speaker Jim Rohn claimed that we’re the average of the five people we spend the most time with.

Since assertiveness has to be learned, it’s normal for it to be awkward at first. Just as we grope our way through our sentences when we’re learning a new language, acting assertively is uncomfortable for the novice. Practice makes assertiveness easier, just as it improves language fluency.

How do we practise assertiveness, though? There’s no Duolingo for assertiveness, no dictionary to consult, no rules of grammar to tell us what’s allowed. Here’s where the Aristotelian role model comes in. Unassertive people typically know plenty of assertive people; indeed, often it seems that the more frustrated we are by our own lack of assertiveness, the more preoccupied we are with people who would never put up with what we put up with. Fond as we are of torturing ourselves with unfavourable comparisons to assertive people, our awareness of what skilled assertiveness looks like in other people is exactly what can help us out of our diffident ruts. That colleague or author or fictional character who would have declined the extra work that you just took on – how would she have done that, exactly? What would she have said? What body language would she have used? Once you’ve worked that out, do the same yourself. Focusing on your role model is an effective way to escape all-or-nothing thinking. When you find yourself thinking, If I stand up for myself, I’ll seem arrogant, remember that your role model isn’t arrogant. That’s why she’s your role model.

But what if you’re just not that sort of person? What if everyone knows you’re accommodating – that’s why they come to you with their requests? Fortunately, none of this matters. You’re not constrained by your past behaviour or by other people’s perceptions of you. Remember: the virtues need to be learned, and you learn them by practising them. As soon as you act assertively, there’s an obvious sense in which you’re an assertive person. Of course, when we say things such as ‘She’s an assertive person’, what we often mean is that she acts assertively often and easily. But that just means that she’s developed the habit of assertiveness. That’s something you can do too, through practice, one act of assertiveness at a time.

There are strategies we can use to grow into our assertiveness. Often, when someone makes a demand of us during a face-to-face conversation, we feel ‘put on the spot’. We either say no now, or we’re doomed to yet another unwelcome burden. But this is another example of all-or-nothing thinking. Your role model wouldn’t view herself as put on the spot, right? She’d know that if someone is demanding something of her, she’s entitled to spend time considering it. Perhaps she’d say: ‘Let me get back to you tomorrow about that,’ or: ‘Ask me again in a week.’ Not only does this buy you time; it also enables you to say no by email rather than face-to-face. But if an answer is required right away, face-to-face and with no time to think, try taking a breath, channelling your role model, and saying: ‘I can’t commit to that right now.’

You can’t stop people making demands on your time and energy, but you can develop the skills to protect yourself – and doing so isn’t arrogant, selfish, uncooperative or any of the other things you’re worried about. Think of the Aristotelian spectrum. Think of your assertiveness role models. Think of the character you’re developing every time you say no. Then invest that time you just protected in the projects and interests that you care about.