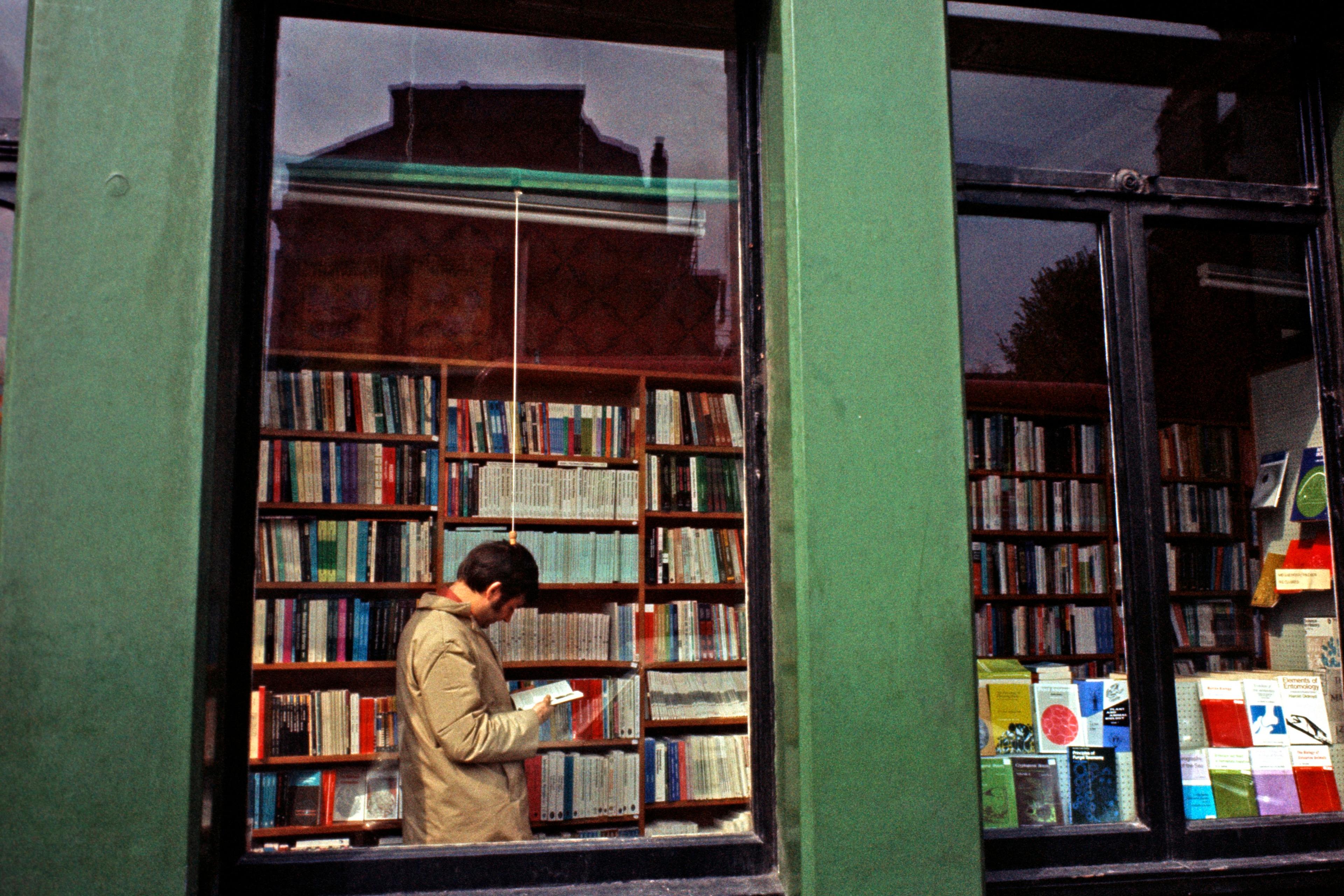

I usually start the year with the goal of reading more books. But, this year, my goal is to read just one: War and Peace (1869).

Leo Tolstoy’s novel has been on my shelf for years, but lighter and shorter fare has always come between us. ‘I’ll read this one quick, easy novel,’ I think, ‘then I’ll give Tolstoy my full attention.’ Years passed. Until I encountered the idea of the ‘slow read’, via Simon Haisell’s newsletter Footnotes and Tangents. It’s Haisell’s third and final year running an online club for this particular novel, producing podcasts to accompany each week’s reading, and in 2025 his subscriber list has swelled like the ranks of the Napoleonic and Russian armies advancing towards each other, with me among their number.

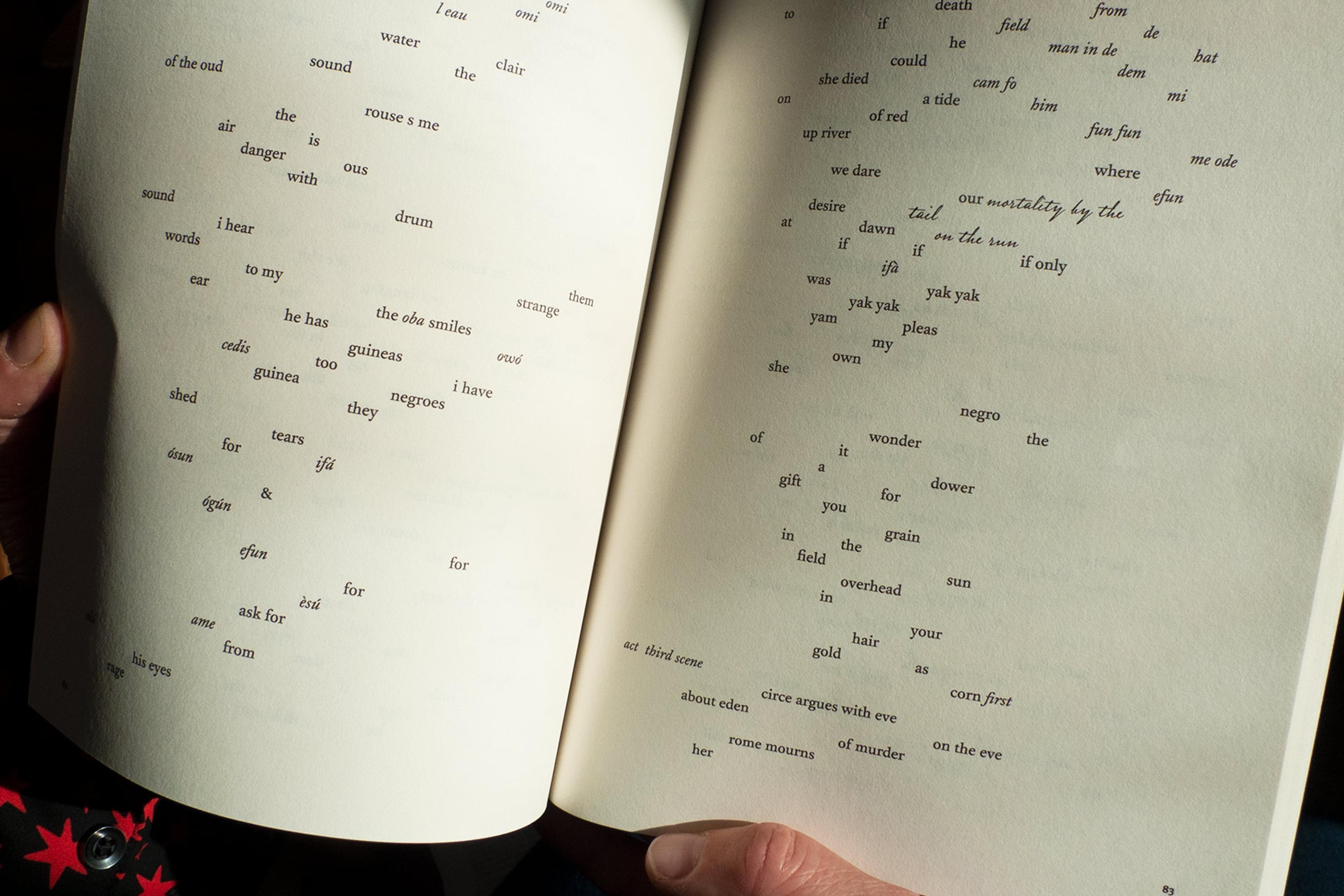

War and Peace has 361 chapters, most shorter than 10 pages. Having started on 1 January and reading a chapter a day, I can expect to reach the epilogue not long after Christmas. This makes my experience similar to how the earliest version of the story, published in weekly newspaper instalments, was read. Now more than halfway through the year, my sense of time has shifted in response to this routine. The book as an object has become a talisman, a tangible manifestation of how a daily habit can build into a much bigger accomplishment: the growing section of pages in my left hand marking out the year so far; the dwindling section in my right hand showing the year yet to unfold. On the left is what is done and cannot be changed; on the right are possibilities still open, choices yet to be made, days to be filled with activities of my choosing. If this is what I can achieve through an extra 15 minutes of reading a day, what else could I add to my life in a similarly manageable, daily microdose? My guitar calls to me from across the room, and the Duolingo owl hoots softly, menacingly, from my phone.