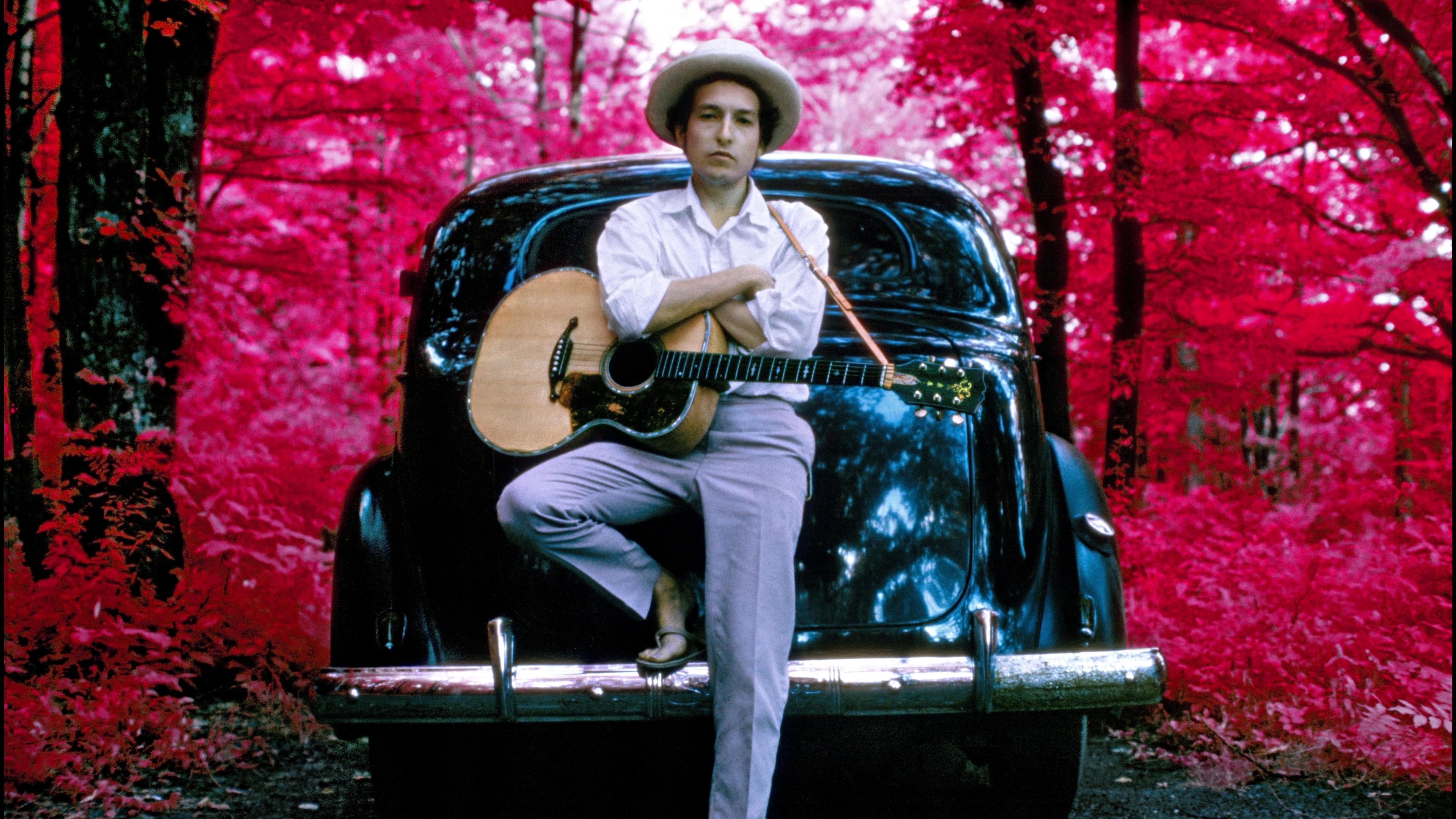

In 1961, after he’d dropped out of university in Minnesota, Robert Zimmerman travelled to New York to become a folk singer, renaming himself Bob Dylan. Initially, Dylan presented himself as an imitator of the Dust Bowl singer Woody Guthrie, whose nasal twang and rural accent he took on. Yet there were limits to a career built on the performance of Guthrie’s songs. The Dust Bowl was two decades in the past, and songs about migrating to California or building the Grand Coulee Dam sounded quaint. New songs were needed. Dylan’s evolution from imitator to original artist illustrates the changes in American folk music, and shows how a strong artistic personality can reshape tradition.

From the first descriptions of ‘folk culture’ in the early 19th century, folk music has been understood as a communal art: the voice of a collective. Songs that had been handed from generation to generation – ‘Man of Constant Sorrow’, for example, or ‘Pretty Peggy-O’ – offered glimpses into an unofficial history comprised of the desires and sensibilities of common people. In the mid-20th-century United States, the collective aspect of folk music took up residence in Left-wing political circles. Through such artists as the Weavers or Odetta, folk music came to be thought of as the ‘authentic’ voice of marginalised peoples. With the advent of the long-playing record, the songs of the past became available to singers in the present, and often juxtaposed in surprising ways.

‘No poet, no artist of any art, has his complete meaning alone,’ wrote the poet T S Eliot in his essay ‘Tradition and the Individual Talent’ (1919). Eliot was concerned to point out that all art builds on tradition, and that the modern artist creates her own voice less through an effort of ‘self-expression’ than by internalising and recombining elements from the work of earlier writers. An individual poet’s own emotions might be of modest intensity, Eliot noted. But they become powerful through a process of ‘fusion’ – that is, when filtered through a vocabulary absorbed from the past. You can see how a powerful poetic personality of the type identified by Eliot might find a voice in the tradition of folk music. In Dylan’s case, his project lay in activating the vocabulary of the past while finding his own voice in the present.

When Dylan began to write his own compositions, he shamelessly borrowed from folk forms, taking Eliot’s idea of ‘tradition’ as ‘fusion’ and reshaping it. His earliest compositions are imitations, reworkings of older songs. Some are anonymous, ‘traditional’ songs, but others have recognisable models, including Guthrie. ‘Song to Woody’ (1962), from Dylan’s first record, uses Guthrie’s ‘1913 Massacre’ (1941) for its melody and structure. ‘With God on Our Side’ (1964) borrows the traditional melody ‘The Merry Month of May’ via the Irish ballad ‘The Patriot Game’ by Dominic Behan. Meanwhile, ‘Blowing in the Wind’ (1962), Dylan’s most famous song, is a reworking of an old slave lament, ‘No More Auction Block’. These early Dylan compositions are haunted by the ghost of a folk-song tradition that seems to ring through them, like a distant echo.

Yet even as Dylan revives the folk-song tradition, he brushes it aside. Take, for example, his first great composition, ‘A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall’ (1962). The song, which offers a visionary account of injustice and violence in the contemporary world, is justly celebrated. Allen Ginsberg remembered weeping when he first heard it, since it seemed to fuse music and poetry in a way that his friends in the Beat Generation had tried to do in the 1950s, using jazz. Much later, Dylan chose the song for Patti Smith to perform when he was awarded the 2016 Nobel Prize for Literature. ‘Hard Rain’ is based on an old Anglo-Scottish folk song called ‘Lord Randall’ that Dylan might have heard from his friend Harry Belafonte, who recorded it in 1954. ‘Lord Randall’ features a conversation between a dying young man, poisoned by the girl he loves, and his mother. Dylan explodes this scenario of fatal love: ‘Where have you been all the day, Randall, my son?’ – the original opening – becomes ‘Oh, where have you been, my blue-eyed son?’ The legendary folk character is now any young modern male. The image is a cliché (though Dylan himself has blue eyes); listeners familiar with folk music might recall the Carter Family’s ‘Bring Back My Blue-Eyed Boy’ (1929), another song about love and death. Here, the blue-eyed boy has been out in the world and is returning with a message that things are not well.

While much of the music around Dylan featured young people criticising war and racism, Dylan’s song brilliantly includes two voices, parent and child. The ‘generation gap’ is thus built into the song, with youth telling age what’s going on out in the world. ‘Hard Rain’ is a protest song, but not one that preaches to the older generation, since all the parent does is ask a set of questions: ‘Where have you been?’ ‘Who did you meet?’ If folk music embodies the passage of culture from one generation to another, Dylan’s song dramatises the problem of historical change, of the wisdom of the old meeting the impatience of the young. The song brings the mythical past of deceitful lovers and tragic passion into a completely contemporary setting.

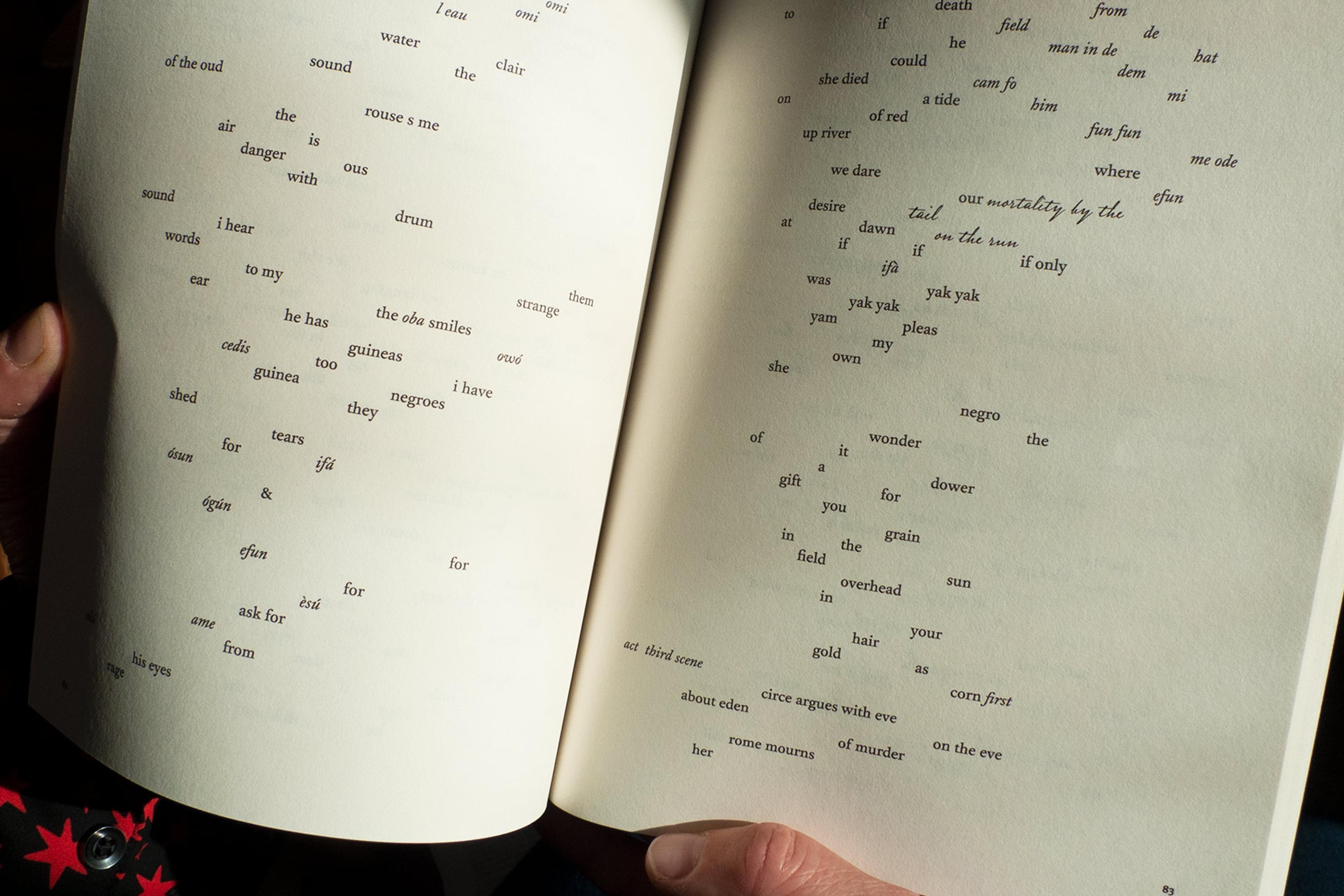

However, the true innovation is in the language of the song, which speaks two or three languages – by which I mean different versions of American English – at once. There’s the archaic phrasing of the parent, who calls the boy ‘my darling young one’ – a completely antiquated form of address in 1962. The phrase makes the song feel old. It comes from the world of ‘Lord Randall’, where the mother calls her boy ‘my pretty one’. Mixed in with this antiquated language is the literary language of prophecy and myth. ‘I’ve been out in front of a dozen dead oceans,’ sings Dylan. ‘I’ve stepped in the middle of seven sad forests.’ This is the language of the King James Bible: ‘I saw the seven angels which stood before God, and to them were given seven trumpets,’ says the Book of Revelation. Here the repeated consonants lend the song its beautiful sonic sheen – ‘a dozen dead oceans,’ ‘seven sad forests,’ ‘twelve misty mountains’.

But there’s more. We hear a language of lyricism to appeal to the lovers in the audience. ‘I met a young girl, she gave me a rainbow,’ says Dylan the romantic. And this, in turn, bumps up against phrases we might hear from a biology professor (‘the pellets of poison are flooding their waters’) or a social reformer (‘the executioner’s face is always well hidden’). Easy allegory (‘I met a white man who walked a black dog’) intersects with obscure images (‘a white ladder all covered with water’). Summing it all up is the arch diction of Dylan’s refrain, which seems to come from somewhere in rural America: ‘a hard rain’s a-gonna fall’. It works by way of rural colloquialisms that intensify verbal expressions, ‘I’m a-goin’’ being another example. The song sounds ancient in its language, rural in its diction, yet completely contemporary in its theme.

‘I contain multitudes,’ wrote the poet Walt Whitman. For him, this involved assuming the identities of people from all across America, to celebrate their experience, while imposing his own implacable poetic voice on American life. Dylan’s approach is not to assume personalities, but to mobilise the range of American languages, pasting them together into a new whole. He is a collage artist, blending phrases and images from diverse sources. In the process, he reinvents folk music, shaping each song as a mosaic of expressions, collected by the singer. Dylan sings not only the song, but the American language as a shared medium. He reimagines the traditional ‘folk song’ community for the era of recorded sound.

This new folk song, as collage, also recasts the fictional role of the singer. Dylan doesn’t create ‘characters’ who express themselves with psychologically realistic phrases. He avoids ventriloquism. Instead, his songs function as sites, or meeting places, where themes, phrases, images and expressions from far-flung traditions come together to form a new tissue of meaning. Dylan’s singing persona emerges, not as the repetition of some earlier folk-song type (a moonshiner, an outlaw, a Dust Bowl refugee) but as the vehicle of the entire American language, from Hiawatha to John F Kennedy. This is why, across his career, he has been able to insert dialogues, conversations, movie plots and lines from novels into his songs. And it’s why his persona remains vital today, 60 years on. Dylan lives in his songs, but he is not of them.

In fact, Dylan might best be seen as a historical poet – a collector of documents and artefacts. He’s keenly interested in historical events (he has many songs about historical figures) but he’s more interested in how we learn from the past. His songs are an intervention into the tradition of folk, marking a historical shift in the dynamics of songwriting: after Dylan, folk music speaks a language both new and old. In repurposing tradition to create a new emotional vocabulary, like Eliot’s modernist poet quoting old lines to speak anew, Dylan turns the idea of the collective folk song against itself. In his songs, the folk tradition rings out, but through the individual talent – so that, while tradition speaks from the past, its voice is reshaped by the singer, who interweaves folk-song clichés with beatnik poetry and philosophical commentary.

At first, Dylan’s innovations confused his listeners. Because he seemed to speak with so many voices, it was difficult to pin him and his songs down. What did they mean? In a 1963 radio interview, the journalist Studs Terkel asked Dylan about the ‘rain’ referenced in ‘Hard Rain’. Terkel was accustomed to the folk song as journalism or proletarian history. For him, the words of folk songs should mean specific things, recalling events that could be pointed to – the Johnstown Flood of 1889, say, or the Harlan County mining strikes. ‘Is it atomic rain?’ he asked, searching for an explanatory key. ‘It’s not atomic rain,’ said Dylan, ‘it’s just a hard rain.’ By his insistent literal-mindedness, Dylan preserved the mystery of the song. ‘A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall’ is the first truly modernist folk song, speaking from deep in tradition, but reworking that tradition to warn of the deluge still to come.