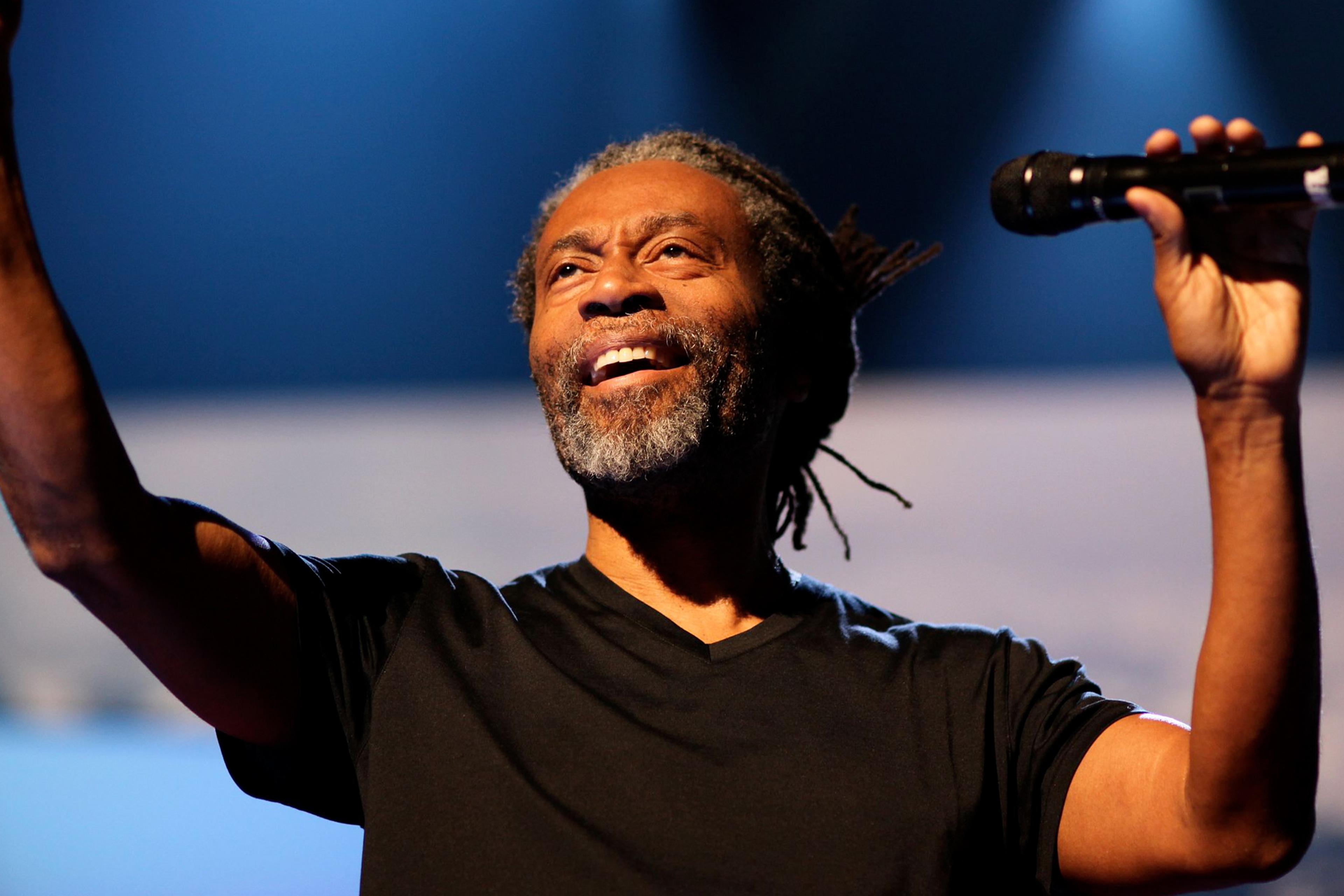

Some musical rhythms are like magic spells: when we hear them, many of us can’t help bobbing our heads, swaying in time, animating our arms and legs. The feeling we have in that moment has a scientific name: the ‘pleasurable urge to move to music’ (PLUMM).

I learned about PLUMM from a paper on why some rhythms incite that feeling more than others. It has a lot to do with the complexity of a rhythm. Previous research has shown that very simple or very complex rhythms provoke relatively little urge to move – likely they seem too predictable or too unpredictable, respectively. People tend to feel the most PLUMM when they hear rhythms of medium complexity (ie, those with a moderate amount of syncopation, or off-beat emphasis).

According to the researchers Alberte Seeberg, Tomas Matthews and colleagues, moderately complex rhythms hit a ‘sweet spot of predictability’, and the effect has been interpreted in light of the predictive processing framework in neuroscience. Recently, these researchers found that when a rhythm contains more than one drum sound (such as a combo of bass drum, snare and hi-hat), the advantage of medium complexity is more pronounced.

I love beats of many kinds, and this research got me thinking about why they make me feel the way they do. At the lower end of complexity, there’s a minimal techno rhythm like this one by The Field – great for focus, but it doesn’t inspire me to move. On the very complex end, a spiky, complicated rhythm by Autechre is something to get lost in, but good luck finding a way to dance to it. So what’s in that sweet spot? We all can think of dance-floor favourites, but try this track by Flying Lotus – a core pulse you can follow, seasoned with little surprises. Commence head-bobbing.