After her son’s death, 59-year-old Mare Lucas often woke up screaming. In her dreams, she would see her son Zane, and then slowly realise that he was gone. ‘I would start reliving the shock that I went into when he died,’ she says.

Zane died by suicide in 2017, when he was 18 years old. In other nightmares, Lucas would be trying to save Zane from kidnappers or from falling off a steep cliff. Sometimes unseen pursuers chased them, and she lost him on a dark city street. Lucas feared going to sleep. ‘It was like constantly reliving his death,’ she says. ‘Either the shock of it, or the fate of it.’

Then, Lucas was diagnosed with breast cancer. In August 2022, she went to Stanford Health Care, near her home in Palo Alto, California, for a lumpectomy and was put under anaesthesia. She had another dream – but this one was not a nightmare. She hovered above herself as she watched her younger son being born, and then Zane’s birth. She wasn’t only an observer, she absorbed the emotionality of the scene. ‘I was sucking in all of the joy and the beauty,’ she says. The dream shifted, and she saw the two boys running through a green park. Zane was a teenager, and he was playing with Moxie, Lucas’s dog.

It had pained Lucas that Zane would never meet Moxie. She had gotten her, in part, to make up for not getting Zane a dog when he was alive. When she woke up from surgery, she tearfully thanked the doctors for the time spent with her son. A month after surgery, Lucas no longer met the criteria for PTSD. She hasn’t had a nightmare since that surgery, which was 18 months ago.

Lucas credits improvement in her symptoms to her anaesthesia dream – and she isn’t alone. She is part of a small group of case-study patients who say that dreamlike states emerging out of anaesthesia made their nightmares, anxiety or distress following a trauma vanish.

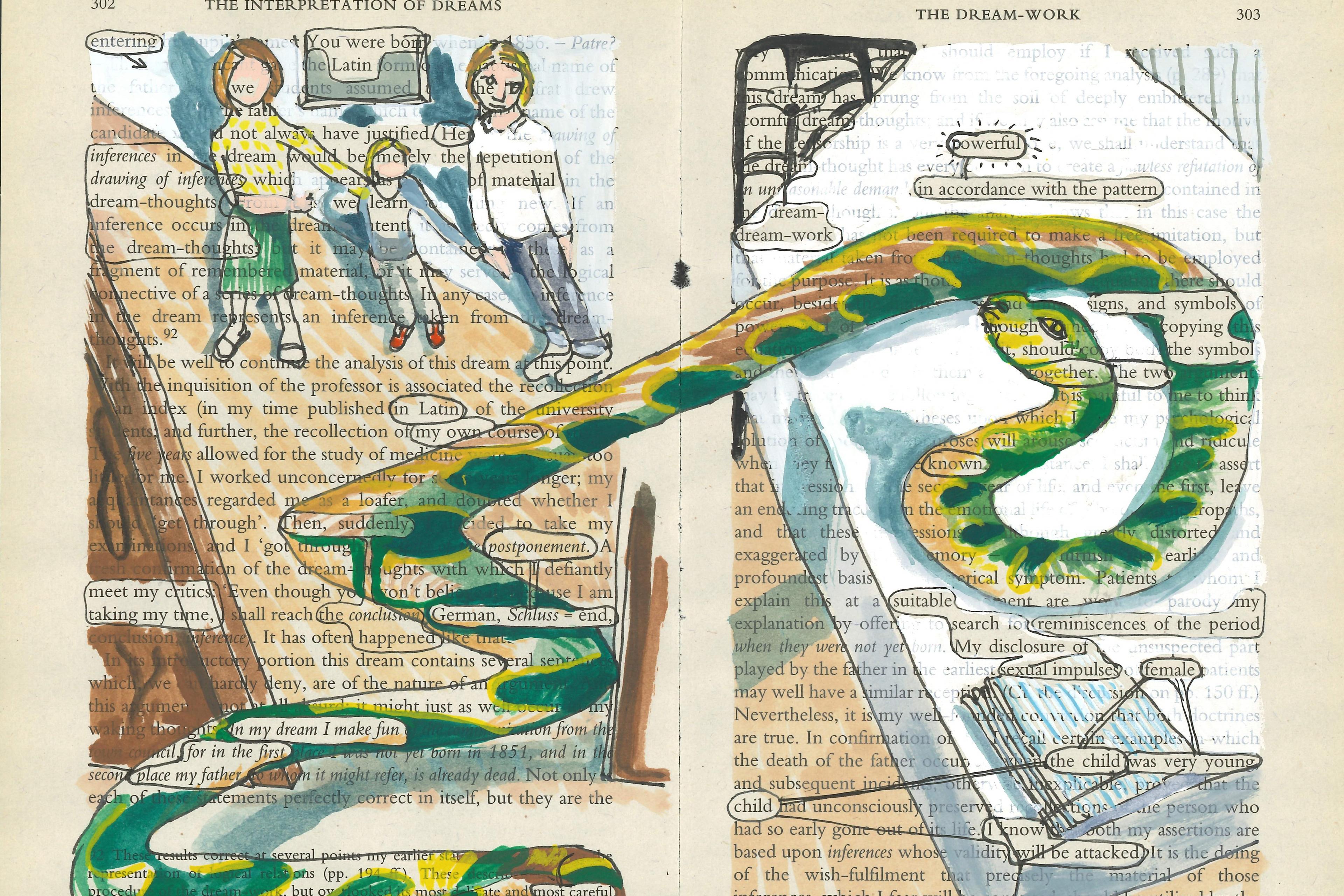

Sigmund Freud wrote that ‘Dreams are never concerned with trivialities; we do not allow our sleep to be disturbed by trifles.’ But our dreams are unwieldy. They do seem to be populated by random childhood classmates and silly meandering plots, alongside lost loved ones and emotional breakthroughs. We wake up remembering dreams vividly, until they evaporate into thin air. An interdisciplinary group at Stanford University is now studying anaesthesia dream states and if they can be harnessed for potential therapeutic effect – asking if a powerful experience we have while unconscious can make an impact on our waking life.

The group at Stanford is made up of anaesthesiologists, psychologists, psychiatrists and neuroscientists, and they presented Lucas’s case in a paper published in March 2024. Another patient in the paper was a 72-year-old woman who suffered from nightmares about her son who died in 2000 from alcohol poisoning during hazing at a fraternity. She also dreamed under anaesthesia about spending time with her son, and her nightmares abated after surgery.

These were not the first dreaming patients Harrison Chow, an anaesthesiologist at Stanford, had seen. In 2007, one of Chow’s patients told him that after she’d had surgeries for a foot issue, her PTSD symptoms had improved. She had been sexually abused by her mother’s boyfriend, and in a dream under anaesthesia, she woke up in her bedroom and was able to escape. This surprised Chow. ‘When we give anaesthetics, we’re supposed to give them and they’re supposed to go away,’ he says. ‘They’re not supposed to have long-term neurological effects.’

They found that 22 per cent remembered dreaming while coming out from anaesthesia

The team’s first published case study, from 2022, was about a woman who’d had surgery after a knife attack. She had held up her hand to protect herself, and the knife had severed several of her tendons and nerves. In her dream, she relived the attack, but this time she went straight to the emergency room, had surgery, and left with a healed hand. In the dream, she saw her hand as uninjured and ran banal errands. After surgery, she slept normally for the first time since the attack, and didn’t have any nightmares. She told her doctors that she felt calm enough to tell her family about the attack for the first time.

Chow did not set out to study anaesthesia dreams. All of these patients were part of a programme to help with recovery after surgery that uses intravenous, and not inhaled, anaesthesia, and involves a more gradual emergence from the anaesthetic state. The patients were also told they might have dreams, and were asked to share if they remembered any.

Dreaming under anaesthesia isn’t uncommon. A study from 2007 found that out of 300 people, 22 per cent remembered dreaming while coming out from anaesthesia. But when Chow asked around to other anaesthesiologists, some had heard about dreaming but hadn’t looked into it closely, and certainly weren’t focused on potential therapeutic effects.

‘We’ve done hundreds of these now,’ says Boris Heifets, an anaesthesiologist working alongside Chow. The group has conducted about 625 dream surveys thus far, representing some 500 patients (including those having multiple surgeries or multiple dreams).

One critical care physician, Sam Parnia, compares the dreams reported by Chow to another intense experience sometimes recalled after surgery – often called the near-death experience, or NDE, induced when patients get extremely close to death. NDEs can have similar content and provoke a similar profound response. In the 1975 book Life After Life, the physician Raymond Moody presented NDE reports from people who had survived comas. Many people said they’d had out-of-body experiences and feelings of peacefulness. They had also often encountered their deceased relatives.

‘The simplified version of the so-called NDE is you just see a light, a tunnel, or your life flashes past you and you come back,’ explains Parnia, an associate professor of medicine at NYU Langone Health who researches resuscitation and what is going on in people’s minds during and after a heart attack. ‘That doesn’t do it justice. There’s so much more to it.’

What the anaesthesiologists in the Stanford team have been observing might be closer to these kinds of memories, and not dreams, says Parnia, who wasn’t involved in the anaesthesia work. A recalled experience near death can also affect people positively. ‘They’re less afraid of death, and less materialistic,’ Parnia says. ‘It can relieve PTSD-type symptoms they may have had.’

It’s striking that certain kinds of recalled experiences can change us for the better. ‘This may be something that can be used for therapeutic purposes in the future, if we understand it better,’ Parnia says, though he added that more research is needed to understand what’s going on in the brain.

A nightmare is so emotionally negative that people wake up and can’t continue the dream

At the start of their research, the anaesthesiologists weren’t monitoring the brain, but they are now, using an electroencephalogram (EEG). Chow says they believe they have detected a rough pattern: reduced alpha waves and increased beta waves in the frontal cortical part of the brain. This combination of activity might be a clue indicating that dreaming is happening during sedation.

After studying the brain waves, Pilleriin Sikka, a postdoctoral scholar in anaesthesiology at Stanford, agrees with Parnia that the altered dream state encountered under anaesthesia signals neither REM nor non-REM dreaming. Non-REM, including deep-sleep, dreams are shorter, more thought-like and less emotional. REM, or rapid-eye-movement, dreams are thought to be more vivid. Sikka views anaesthesia dreams as a form of ‘disconnected consciousness’: when a person is disconnected from the environment, but conscious of their own inner world. This is different from ‘connected consciousness’, or when a person is in a dreamlike state, but still in tune with their surroundings, like when having hallucinations or a psychedelic trip.

There are many theories for the purpose of dreams. Some argue that dreams help consolidate memory to reprocess our experiences. The continuity hypothesis proposes that dreams reflect our current concerns, and another set of theories suggests that dreams help tune down the emotional volume of some events as we experience them again. Most of these theories require a dream to ‘continue and follow its path’ so that you can ‘work through’ it, Sikka says. ‘What happens in nightmares is that a nightmare is so emotionally negative, so arousing, that people wake up and then can’t kind of continue or complete the dream.’

One of the team’s guesses is that because anaesthesia puts the body into a low-arousal state, it allows a dream that is more like a nightmare to unfold. ‘Reprocessing these memories on this baseline low-arousal state induced by anaesthetics and letting the dream kind of continue, might perhaps help to down regulate these negative emotions,’ Sikka says.

People are experiencing these dream states with a variety of anaesthetic drugs and combinations of those drugs. It’s possible that simply suppressing people’s arousal with general anaesthesia is what’s driving the nature of the dreams. Heifets says it’s also possible that there’s something about one of the drugs, such as propofol, that’s responsible – they’ll need more research to find out.

What the team wants to do next is an experimental study of non-surgical cases, where anaesthesia dreams are intentionally induced in people diagnosed with PTSD. If the researchers can keep their subjects in the state of disconnected consciousness for 15 or 20 minutes, longer than what has been sustained in the surgery patients thus far, they may be able to monitor changes in the dream experience over time.

Heifets says they haven’t seen anyone have an adverse reaction to their dream experiences – yet, but he wants to be sure to pay attention to the possibility. These patients are overwhelmingly having positive dreams. In the surveys conducted by the team, patients are asked to rate the emotional tone of their dream from 1 to 5, and the majority of people, around 85 per cent, have said they are very positive. Only one person reported a slightly negative dream, in which they felt sad while talking to their grandchild about their diagnosis – but this was not a nightmare.

In the dream, they were in a cove that looked like the spot in California where she spread Zane’s ashes

The applicability of anaesthetic dreams for mental health conditions has yet to be fully tested, but the concept fits into a growing approach in psychiatry: the value of a transformative experience – brought on or encouraged by drugs – to promote healing. ‘These are experiences that usually occur rarely, but when they do happen, they can change your self-concept of how you see other people, your values, and your wellbeing,’ Sikka says.

Last July, Lucas had another surgery, and another anaesthesia dream. She loves visiting Maui, Hawaii and Zane loved the beach, but they were never able to go there together. In the dream, they were in a cove that looked like the spot in California where she spread Zane’s ashes, and it also looked like Hawaii: blue water and palm trees.

Lucas wasn’t herself; she was a large bird. She was circling in the sky above her family, including Zane, her other children and her husband. ‘I could hear them playing and laughing’, along with the sound of the waves crashing. Eventually her left wing started to hurt, and she worried about falling – she woke up and the left side of her body was in pain from the surgery. Even though she wasn’t plagued by nightmares anymore, the dream was a welcome experience. ‘I got to see Zane on the beach again,’ she says. ‘He was with the whole family.’