Most of us have had the experience of waking from a dream that was so incredible, bizarre or moving that we can’t wait to tell someone else about it. You’ve probably been on the receiving end of other people’s stories of their dream adventures too. As a sleep scientist, for years I’ve wondered about what’s really going on during these conversations and what they might tell us about the nature of dreams.

In 2016 I began hosting public dream discussions with my collaborator, the artist and academic Julia Lockheart. At these events, I discuss a volunteer’s notable dream with them in front of an audience and, as we’re speaking, Lockheart creates an artwork based on the dream. I remember one event in particular from 2017: our volunteer’s dream was a metaphorical description of the emotional impact of her daughter leaving home. The dream was so poignant, everyone in the audience was deeply moved. Lockheart and I realised then that discussions of dreams could affect the listeners just as much as, and sometimes even more than, the dreamer themselves. Further, we realised this might shed light on one of psychology’s greatest mysteries – why do humans dream at all?

Whether dreams and dreaming have a function has been debated for years. On the one hand is the view that dreams are an epiphenomenon, a functionless byproduct of daydreaming processes that continue into sleep. In his book Dreaming Souls (2000), the neurobiologist Owen Flanagan describes dreams as decorative ‘spandrels’, a term evolutionary biologists use to describe features of an organism that don’t seem to serve any purpose for survival or reproduction.

On the other hand, many scientists have proposed various functions of dreams, but overwhelmingly based on the idea that this function occurs via neural processes that take place during sleep, regardless of whether the dreams are later recalled or not. Examples include the suggestions that we simulate and practise overcoming threats in our dreams, that dreams play a role in consolidating memories or regulating emotions, or that they produce imagery that helps us cope with scary memories from waking life. However, findings that accord with these theories are all correlational – making it impossible to infer that dreams are definitely causing any effects on memory or emotion. Researchers must wait until they can experimentally alter dreams, such as by targeted stimulation of dream content, to make these causal claims.

Yet dreams have been shown to have causal effects when they are shared after waking. Clues indicating these effects come from correlational work. For example, in one study, couples who shared dreams more frequently also reported greater relationship intimacy. There’s also more robust evidence for the effects of dream-sharing. In an experimental study, researchers randomly assigned participants to one of three groups: dream-sharing, event-sharing (describing events from the day) or a control group. In the first and second groups, participants shared dreams or daily events with their partner for 30 minutes, three times a week for four weeks. Dream-sharing was found to increase marital intimacy more than event-sharing or the control condition. The team, led by the relationship counsellor Thelma Duffey, suggested dream-sharing might enhance relationships by providing a forum for self-awareness and self-disclosure.

That poignant dream-sharing event in 2017 helped inspire Lockheart and me to extend this line of research on dream-sharing and relationships. Our initial investigations uncovered that people higher in empathy tend to share their dreams more often and listen to other people’s dreams more frequently. Next, we studied whether dream-sharing might actually increase the level of empathy a person feels towards someone else. (Such a finding would be consistent with prior research showing that literary fiction – which, like dreaming, is a simulation of social experience – can increase people’s empathy.) We recruited pairs of participants, who were friends or in a romantic relationship. We asked one person in each pair, after having a dream, to meet the other member of their pair as soon as possible, to discuss the dream with them for 15 to 30 minutes. By comparing survey measures completed before and after the dream-sharing, we found that the listeners’ empathy for the dream-sharers had increased. In this study, and a subsequent replication, the dream-sharers didn’t show an increase in empathy towards their listener, likely because the dream-sharer was addressing their own dream and own life during the discussion.

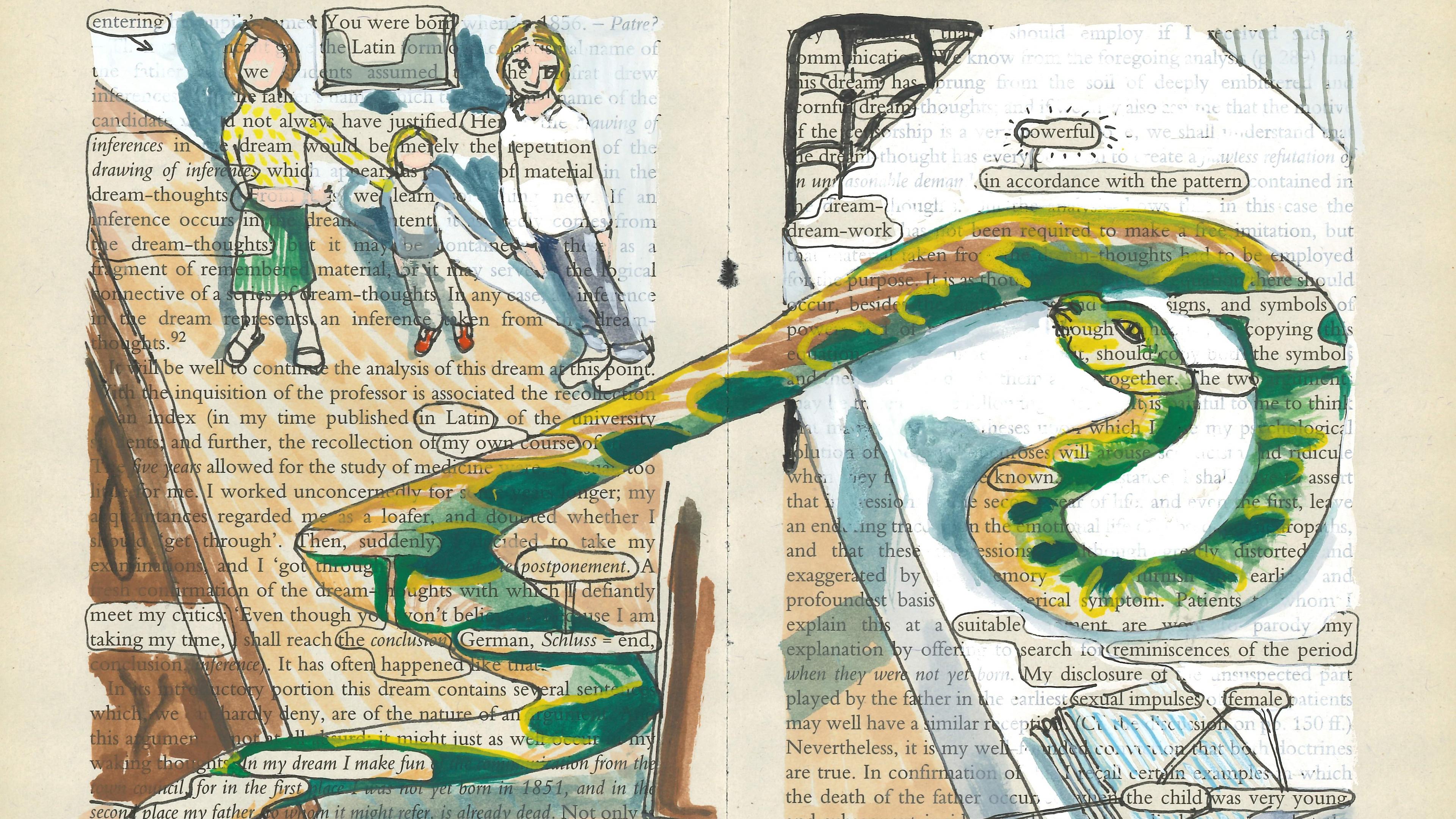

Dream of ghostly children and tidying a chaotic house, told at the Surrealisms 2022 online conference, 19th November 2022. ©Julia Lockheart

It’s easy to see the advantages of encouraging someone else to treat you with more empathy. In our book The Science and Art of Dreaming (2023), Lockheart and I speculate that, across human evolution, people who shared dreams with social, emotional and other story-like aspects of content might have enjoyed a survival or reproductive advantage thanks to the empathy-eliciting function of these kind of dreams.

A rudimentary form of dreaming might have originated across many animal species, for memory consolidation, threat rehearsal or other functions, or for no function at all – as no more than a spandrel. But then, following the development of complex speech in humans, which would have allowed for dream-sharing, evolutionary processes could have begun to shape the components of dream content. This would have occurred on a timescale similar to that of the evolution of human language and storytelling, which commenced approximately 150,000 to 200,000 years ago, and which supported group cohesion and cooperation.

We suggest that the function of dreams resides in their waking use

The wider theoretical context for this places dream-sharing as part of what scholars call ‘human self-domestication’. This major theory of human social evolution proposes that we have domesticated ourselves, just as we have domesticated dogs, cats and horses. It holds that there have been evolutionary advantages for humans displaying reduced aggression and increased tolerance, cooperation and empathy within their social group.

Based on all this, we suggest that the function of dreams resides in their waking use – how they enable self-disclosure, for the benefit of the group, even if it can sometimes be uncomfortable for the individual. The remembering and telling of dreams is thus essential to their evolved function. Of course, the sharing of stories or memories, or even discussing one’s favourite film, can similarly promote self-disclosure and bonding. But perhaps dreams are uniquely conducive to these social benefits because they typically include highly emotional content derived from waking life.

.jpg?width=3840&quality=75&format=auto)

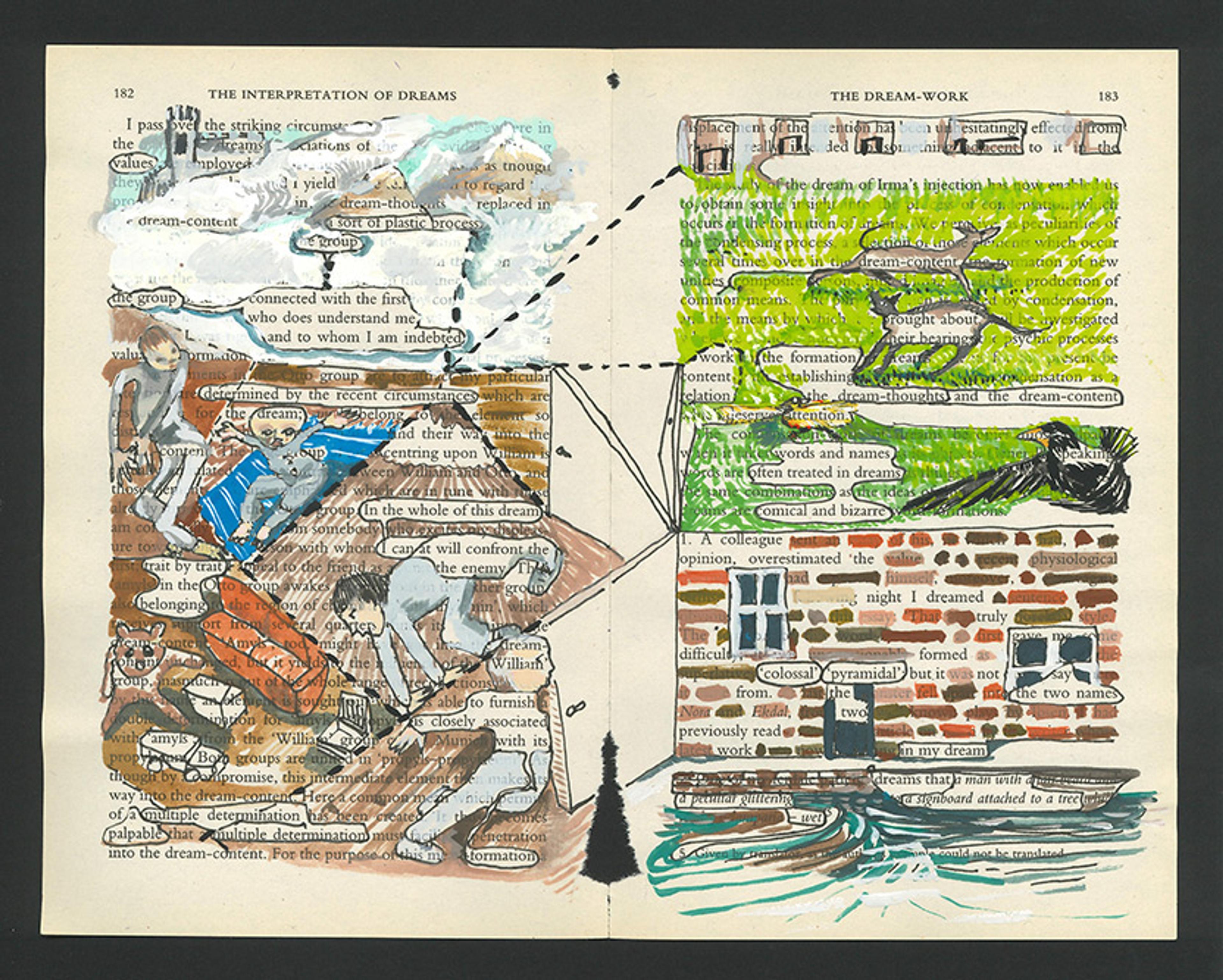

Dream of fighting off an attacker at friend’s apartment and then in the street, told at 39th annual conference of the International Association for the Study of Dreams, Tucson, Arizona, 18th July 2022. ©Julia Lockheart

So, what next? How can researchers weigh up the contrasting hypotheses for the functions of dreaming? We believe that some of the data that’s been used to support dreams having a within-sleep function can be interpreted in line with our own dream-sharing theory.

Consider the findings in 2020 by Monica Bergman and her colleagues, based on their analysis of 632 dreams described by 150 Polish survivors of Auschwitz, collected in the 1970s. These were retrospectively reported dreams experienced before the Second World War, while imprisoned during the war, and after the war. Bergman’s team found that war-related and other threatening dreams were more common after the war than during imprisonment, and that dreams involving family and freedom-related themes were more common during imprisonment than they were before or after the war.

Bergman’s group concluded that this pattern was consistent with dreams being used to process emotions and memories during sleep. However, we think it’s possible to interpret the same findings through the prism of our dream-sharing theory. From this perspective, sharing dreams of one’s prior life, worth and identity could have aided social bonding and empathy among prisoners living through the terrible circumstances of the concentration camp. Similarly, after the war, sharing dreams of Auschwitz could have encouraged social bonding and empathy towards the dreamer for what they had experienced when they were imprisoned. Viewed this way, the dreams could have helped to promote self-disclosure and group bonding, even if this also meant bringing back painful memories for the dreamer. (We think a similar argument for dreams having a post-sleep function can also be made for other recent cross-cultural research into the nature of people’s dream content.)

It is widely believed by the public and by researchers that dreams might be doing something for us, and for our brains, while we sleep. This is because dreams are often complex, and often reflect our lives in a creative and metaphorical way. But Lockheart and I are not the only scholars in this area with reservations about how much the neural processes observed during sleep are relevant to the experience of dreaming and its function. It could be that the function of dreaming plays out, not during sleep, but upon waking, when dreams are told. So, the next time you wake up with a dream fresh in your mind, try to tell it to someone else as quickly as you can. It could be that the dream is meant for them, rather than for you. Like blushing, dreaming might be evolution’s way of forcing you to disclose yourself to others.