We are all familiar with disappointment. We feel it towards personal enterprises, towards political projects, and in the face of wanting to effect social change. Even though we frequently meet with disappointment, things rarely end there. Disappointment might be the unwanted accomplice to everyday life, but the implications of disappointment are not obvious. Disappointment is not followed by a full stop, it is never just disappointment – it is, on the contrary, open-ended, socially situated and politically structured. What I propose here is a defence of the ‘politics of disappointment’.

Disappointment is both personal and universal, both subjective and political. There is undoubtedly a general sentiment of the feeling of disappointment that we all share – a failure of our expectations – and my intention is not to introduce an alternative definition but to reframe this everyday notion of disappointment. To accomplish this, let’s look at disappointment from two perspectives: firstly, as always being political, even in its most personal manifestation; secondly, as real – in other words, as not merely a subjective state, but the reflection of an objective discrepancy in reality.

In order to better conceive of the political dimension of disappointment, its personal function in relation to enjoyment and desire is a useful departure point (it is worth noting that, from a psychoanalytic perspective, desire and politics are difficult to separate as they operate within the same linguistic-symbolic frameworks). Consider the following interaction between a masochist and a sadist: ‘Can you make me suffer?’ the masochist asks, to which the sadist replies: ‘No.’ This joke from the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan’s seminar series ‘Formations of the Unconscious’ (1957-58) is not simply intended to describe a fruitless sexual encounter, but rather reveals an important paradox central to our demands. What the masochist wishes is to be made to suffer, yet this wish is not granted by the sadist. But to not have a wish be fulfilled would itself cause an element of suffering. Hence by not granting the masochist’s wish to be made to suffer, the sadist does in fact inversely grant it. The lesson, for Lacan, is that disappointment is not stable, it has a tendency to reverse into a form of enjoyment. This paradox of disappointment is as much personal as it is political: the fact that the immediate goal of our political desires and projects is inherently unattainable and therefore prone to disappointment makes possible new ways of attaining satisfaction.

The sociologist Dag Østerberg allows us to better understand the freedom that comes with disappointment in his treatise on politics and power. In the political context, a discontinuity is often initially perceived as its opposite, as a fluid continuity of things as they are. A discontinuity simply refers to a rupture in a certain status quo, regime or ‘order of things’, which appeals to social justice or economic freedom. The GameStop frenzy of 2021 was precisely such a discontinuity, which nevertheless obscured itself: if we were to take a snapshot of the relevant hedge funds before and after the frenzy, it would seem that nothing significant had taken place. Yet in this period, the mass investment by Reddit users to buy shares of a stock that was being shorted by corporate hedge funds created a previously unimaginable (albeit short-lived) anarchy. In the space of a few days, Wall Street was facing billions of dollars in losses. Yet this resulted in a doubling down of the financial system being opposed: banks bailed out the hedge fund owners and the market soon returned to normal. The initial discontinuity in a financial status quo reversed itself, and effected a more aggressive confirmation of the status quo.

In sharp distinction to much classical political philosophy, Østerberg recognises the internal discrepancy in the discontinuity: the tendency for a political demand to produce its opposite. Echoing Lacan’s point that a demand often functions only insofar as it negates itself (ie, that it inadvertently acts in the service of the thing it attempts to negate), a social negation is often coloured by disappointment: by the fact that things are able to persist though this very negation. The philosopher G W F Hegel’s term for this was the ‘negation of the negation’, by which he meant that an opposition often bolsters the opposed thing. The ‘politics of disappointment’ is precisely this: in disappointment, a new opening emerges, and it is only in the wake of such an experience that we are better equipped to critically assess that same system that led to our disappointment.

The Occupy movement and its rebellious tech-driven counterpart have rendered capitalism only more adaptable

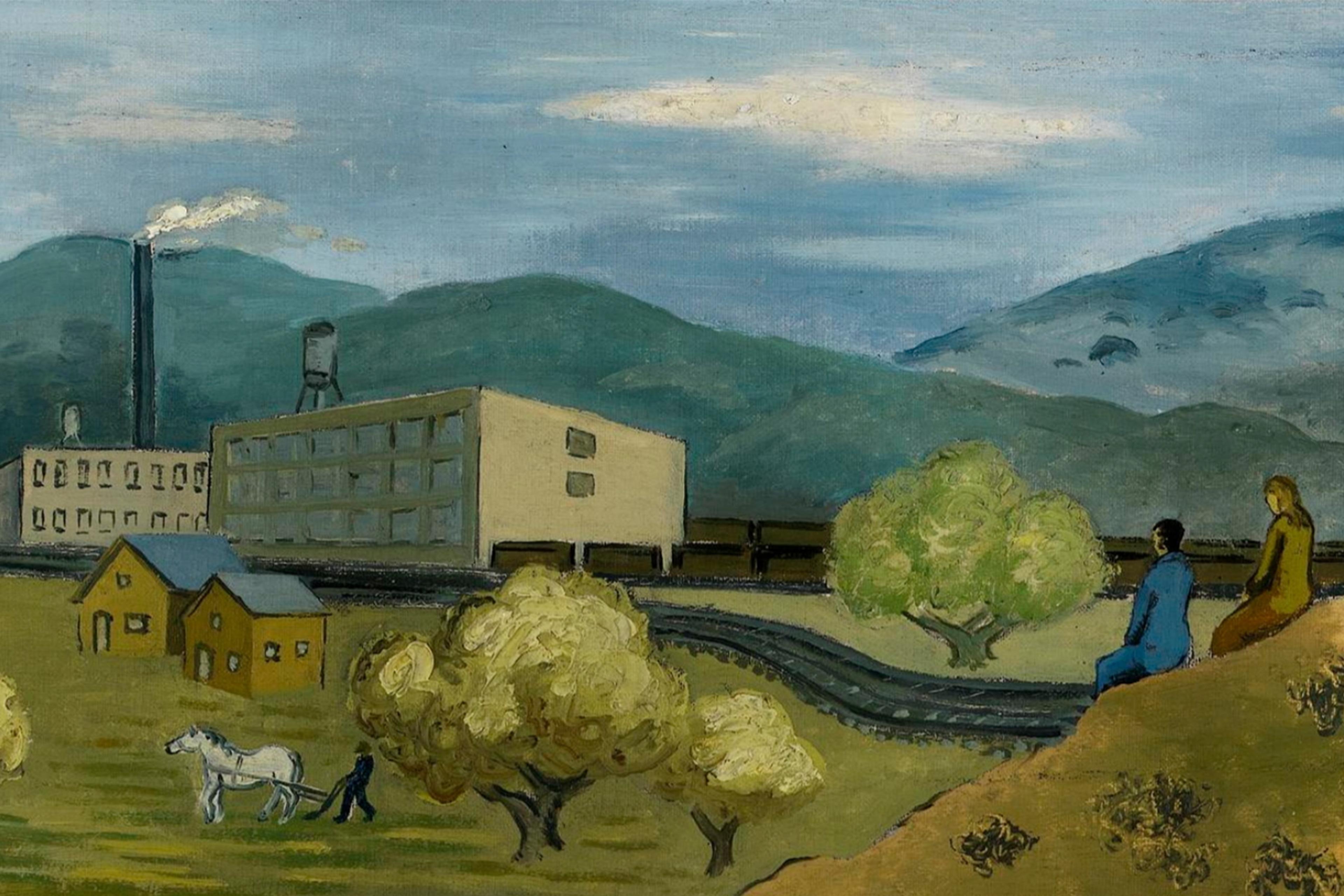

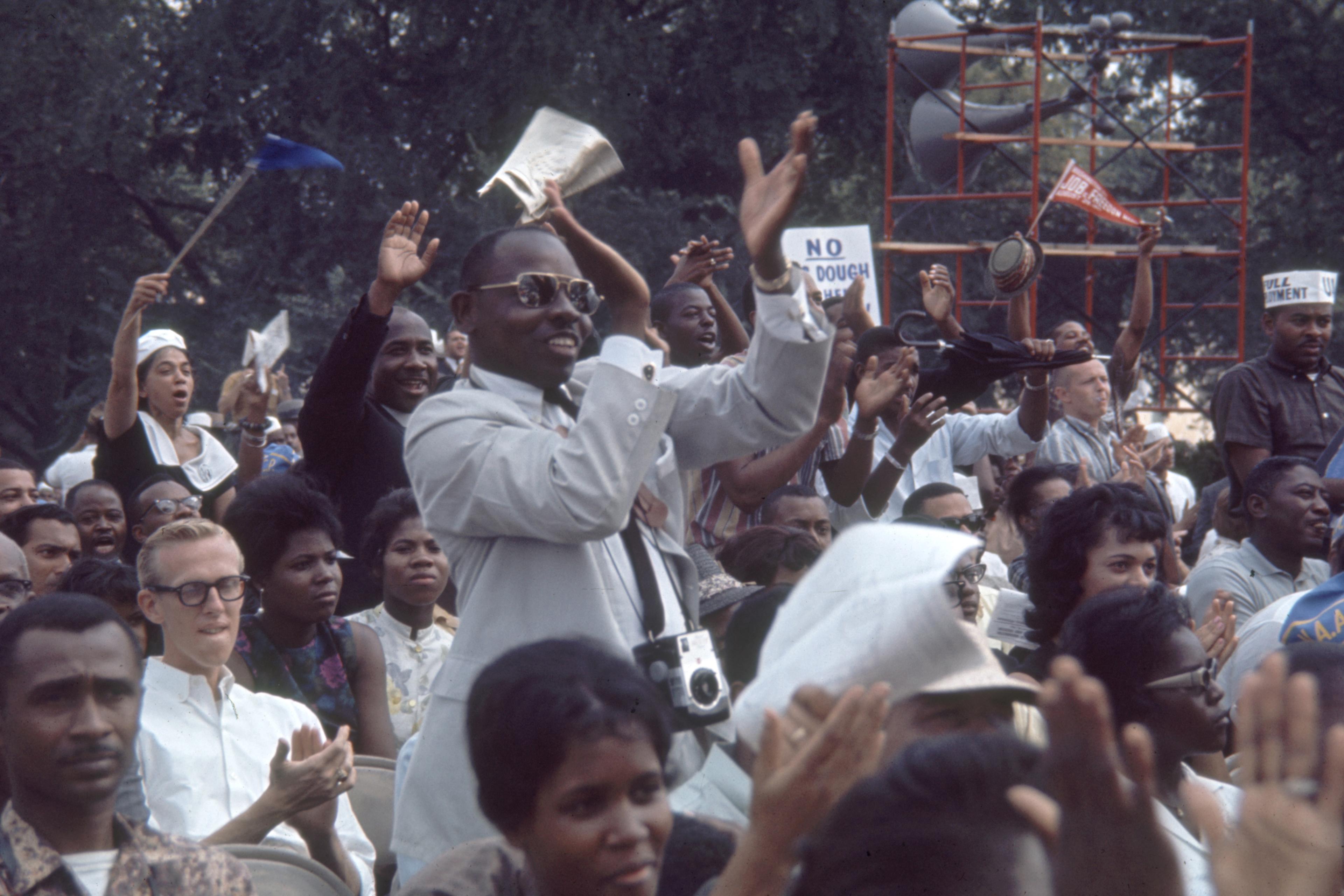

This disappointment of a failed negation is a feature of various political events of the 20th and 21st century. The aggressive US foreign policy of the administrations of John F Kennedy, Lyndon B Johnson and Richard Nixon across the 1960s and ’70s, and the financial manipulation of its media coverage, was only more rampantly deployed when popular anti-Vietnam War protests first emerged: the opposition bolstered the opposed thing. The early voices of dissent against US activity in South Vietnam – actively organising protests and making demands for scaling back US involvement – produced anything but the desired results: the major escalation of conflict known as the Tet Offensive in 1968, and the ensuing destruction of civilian and agricultural production areas across Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia.

Three decades later, the wish for a new ethical alternative to the neoliberal hegemony ushered in by Margaret Thatcher in the UK and Ronald Reagan in the US was met with the disappointment of Vladimir Putin’s even more repressive, oligarchic post-Soviet Russia. In the 21st century, the Occupy movement of the 2010s and its rebellious tech-driven counterpart (including the GameStop frenzy in 2021) have rendered capitalism only more adaptable. Even the prospects of democratic freedom characterising the Arab Spring of 2010-12 were stunted almost in their very conception: the rebound of Arab Winter and a military authoritarianism that wreaks havoc across the Arab world even today.

Yet with each such failure, with each brutal instance of disappointment, a new form of criticism becomes possible. Disappointment is inevitably critical – it expresses a real limit to political systems. Disappointment with things as they are, or with our inability to effect genuine change, expresses a problem in political systems that is not limited to our reception of them, but which comes out of these systems’ inherent imperfections. This dimension of disappointment is worth stressing: what is most important is that disappointment is not limited to a subjective, emotional experience. On the contrary, disappointment has an ‘objective’ value.

This is the second perspective on disappointment: not only is disappointment always political, it is also not merely subjective. It is objective. Though of course disappointment is a subjective feeling, it also registers a very real inconsistency in the world itself. It reflects a discrepancy, and a potential alternative, within real political systems themselves. It would therefore be shortsighted to take a stoic approach in which we convince ourselves that disappointment speaks of our own character and that we must change our attitude. This is indeed the ‘easy way out’, which fails to recognise the objectively critical meaning of disappointment. Disappointment is not an attitude – it should rather be framed as the subjective trace of an objective social disparity.

Political events recur not only as tragedy and then farce, but as a farce that makes possible a more extreme tragedy

The insufficiency of our own experience (that is, disappointment) is not merely ‘our fault’, but the effect of an objective incompleteness on the side of the disappointing thing itself. One’s disappointment with attempts at changing, say, the state-supported financial domination of private corporations does not imply that I need to merely ‘change my attitude’ and accept them, but rather represents the objectively exploitative and hypocritical structure of such institutions, which proclaim themselves to operate along democratic and free-market principles.

This critical dimension of disappointment was important for Karl Marx, who left little room for optimism. Utopian fantasies – which, as Marx and Friedrich Engels argued, are grounded in the optimistic stance that things will automatically get better – had no place in his writings, which dealt with the brutalities of political contradictions and the internal antagonisms generated by increasingly developed modes of capitalist production and circulation. In his essay ‘The 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte’ (1852), Marx gave us his formulation of historical events and persons: they appear twice – once as tragedy, and then as farce. The figure of Napoleon, for example, had to occur once as the despotic tragedy of the Napoleonic Wars (c1800-15), and as farce in the form of his nephew, Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, and the impotent spectacle of his coup d’état in 1851.

At the same time, the inversion of this basic formula appears equally true today: political events recur not only as tragedy and then farce, but as a farce that makes possible a more extreme tragedy. We need not look far back for this: the movement ‘from farce to tragedy’ has been a defining feature of Donald Trump’s political career. In 2016, Trump’s presidential campaign and eventual election was a scandalous farce, absurd enough to be both humorous and shocking. Yet, eight years later, the Republican Party represents something far more destructive than farce. The wish to cut back the administrative state, to abandon climate policies, to ban abortions, and even to prepare for a ‘second American civil war’ represent a definitive step towards tragedy.

We can all be humiliated and impotent optimists – to ‘look on the bright side’ is the easy way out. To side with disappointment, on the other hand, to see endless and cruel repetition inscribed in the everyday, represents a new opening. On the one hand, there is a distinctive element of shamelessness to optimism, to the disingenuous insistence that crises can be handled by a simple change in attitude. Should we instruct the victims of war or natural disasters to become better stoics? Or suggest that the key to handling catastrophe is to avoid slipping into pessimism? Stoicism or optimism are merely methods for upholding a degenerating status quo.

At the same time, the more fundamental flaw of optimism is that it disregards what was stressed above: the co-dependence of the subjective and the objective, of our collective experience and the political-economic structures that frame this experience. In other words, the radical component of disappointment is that it subjectively registers objective injustice in a political regime. Disappointment is a fundamentally critical experience, with a productive potential. The optimistic position is tempting, but lends itself to a reactionary justification of things as they are, placing the blame not on the object itself (political economy, global markets, etc) but on our experience of the object. Disappointment, on the other hand, recognises the role of the object (of a system, a government, a social apparatus) in producing a subjective experience. To defend disappointment is not an abandonment to nihilism; it is a new political perspective, an insistence on the political value of disappointment.

The seeds of the new can be cultivated only in the shadow of failure. Unlike optimism, disappointment carries a uniquely political implication, made possible only by the regime against which it reacts. To recognise the politics of disappointment is to recognise a certain antagonism inscribed in culture itself. Insisting on the need for optimism only reproduces the dire conditions in which optimism is required. To praise disappointment, and to abandon a blindly ‘positive attitude’, is one of the few remaining ethical options available to us.