Nostalgia makes an enigma out of our emotions. When we come across a childhood drawing, a photograph of long-lost relatives or wander along old familiar streets, what comes naturally to us is a sentimental yearning for a moment seemingly frozen in time. This nostalgia can be touching, agonising, exhilarating even, and all at once! We feel a bittersweet emotional catch-22 that is becoming increasingly present in all our lives – from our own personal recollection or fantasies of the past to the cultural retromania of film and TV re-makes and video game ‘re-imaginings’.

Many psychologists today believe that the effects of nostalgia are overwhelmingly positive and healthy. Indeed, that the sweetness outweighs the bitterness. Krystine Batcho, for example, insists upon the beneficial and enriching aspects of the emotion. Speaking on a podcast in 2019, she said: ‘Nostalgia, by motivating us to remember the past in our own life, helps to unite us to that authentic self and remind us of who we have been and then compare that to who we feel we are today.’ Nostalgia is not only good for your mental health but can help create and sustain meaning in your life.

It is now commonly understood that nostalgia can also be a prosocial emotion in the sense that it helps us recognise what is universal to all of us, such as a lost childhood or a longing to be part of romanticised versions of the past. In a humanist spirit, this recognition of a universal feeling of lack then helps us appreciate and relate to the desires of others. For much contemporary psychological research, nostalgia is a perfectly natural and indeed rational adjustment to the loss that makes us human.

But if nostalgia makes us healthier and truer to ourselves, then what possible relationship could this comforting feeling of reverie have with the creeping unease of horror? Where nostalgia reconstructs the past to reassure you that you are (or could be) at home, horror deconstructs these boundaries of security and belonging with the suggestion that something else dwells here, in this home that was never yours to begin with. Nostalgia, surely, is human – warm and soothing. Horror on the other hand is inhuman – cold and jarring.

This distinction was not so clear for the early modern doctors and thinkers on nostalgia only 350 years ago. It is not only that those wistful and innocent longings we all feel when we think of home were once subject to urgent medical intervention and scrutinised as symptoms of a fatal disease. The 17th-century medical-scientific literature possessed a weirdly inhuman and morbid philosophy of the effects of nostalgia, their diagnoses of homesickness resembling a grim tale of the fantastique.

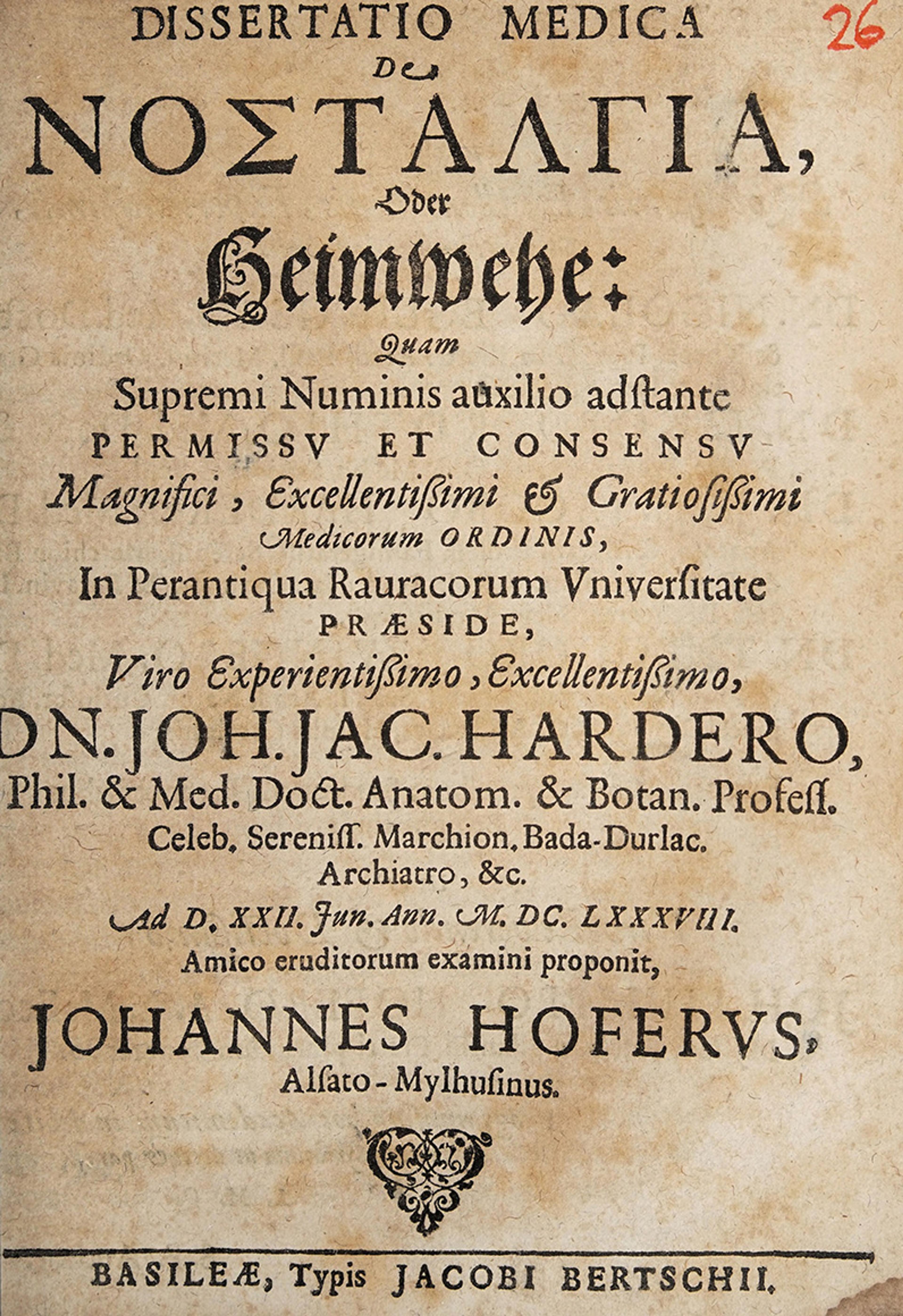

It was the Swiss doctor Johannes Hofer who coined the term ‘nostalgia’ in his influential medical dissertation of 1688. This nostalgia disease was thought to have afflicted mostly mobile classes of people like students, sailors and soldiers, and appeared in a wide variety of debilitating and melancholic symptoms, from insomnia and loss of breath to difficulty eating and a brooding misanthropy. Hofer wrote of the nostalgic patient’s inconsolable distress when thinking and dreaming of their homeland – a longing for return that turns to mania as the mind becomes gripped by homesickness while the body wastes away, leading to death by ‘nostalgia’.

Courtesy the Wellcome Collection

Was there a supposed cure to this illness? ‘Nostalgia … admits no other remedy than a return to the homeland,’ insists Hofer. ‘[T]he patient should be taken away [to their home country] however weak and feeble, without delay, whether by a travelling carriage with four wheels, or by sedan chair, or by any other means.’ This method of treatment reflects the predominant medical opinion of the time, which saw the onset of nostalgia in specifically homesick terms as the loss of a physical connection with a real place of origins.

Nostalgia excites the imagination with the rolling repetition of hyper-romantic images of home

By this logic, the sufferer had become dislocated from the rhythms, traditions as well as climate of their true home and should be re-integrated as soon as possible. Another doctor investigating nostalgia took this idea and developed a specific treatment for Swiss homesickness by lodging patients atop the Alps, believing that the thin mountainous air would provide a strange sort of acclimatising equilibrium for the displaced Swiss, restoring a healthy frame of mind and curing their nostalgia.

But the horror of nostalgia in Hofer’s reasoning was not so much to be found in its symptoms or its cure, but in the alleged source of this pathologised longing for home. Hofer did not think of nostalgia, as we do today, as arising from the personal relationship we have with a memory and the emotional satisfaction or ache we derive from it. It was not even really a question of memory as such. Hofer thought of nostalgia instead as arising solely from an ‘afflicted imagination’.

In other words, your yearning for homely reunion is a danger to yourself because your own imagination that fuels it has become disturbed and possessed by nostalgia. Since you lack what the disease desires, the faculty of your imagination grows in power to fill this ever-widening gap while, at the same time, the rest of your vital functions fall into disorder and deteriorate. Nostalgia excites and agitates the imagination with the rolling repetition of hyper-romantic images of home. An imagination once thought to be under our control has gone awry.

This delirium of longing causes one’s afflicted imagination to essentially gorge itself on the rest of the body, finding solace only in the feeding upon itself in a doom loop of irrepressible yearning and the ever-intensifying circulation of images in the mind (hence the broad variety of symptoms, which Hofer outlined to include ‘wandering about sad’, a ‘distaste of strange conversations’ and ‘scorning foreign manners’). Nostalgia was not just thought of as a disease, but as a parasite – specifically, our own disfigured imagination as this parasite – transmitting alien longings for a lost homeland into the minds of its human hosts. It is as if something is alarmed and panicking about the idea of going home in our place, taking over our consciousness and dragging and wasting the rest of our physical bodies along for this pursuit at its own accord – until eventually it kills us and at the same time, in doing so, itself.

More than 100 years later, in the early industrialised carnage of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars, the nostalgia disease became a crisis for the French army. Thrown into the new regimentation and discipline of early modern warfare, soldiers would be consumed with longing for their local pays or country homes, inducing thralls of melancholia and culminating in fever, insomnia, digestive issues and finally death ‘by nostalgia’. The surgeon-in-chief of Napoleon’s Grande Armée, Pierre-François Percy, echoed Hoferian themes of an alienated homesickness in his instruction to army physicians to ‘grab hold of the patient’s imagination and redirect it away from the object to which it is enslaved.’

This mystery of an (abstract) idea that can make you (physically) ill that nostalgia presented to physicians at the time fascinated a circle of French intellectuals called the Idéologues. Pioneering psychiatrists from the group such as Philippe Pinel insisted on a ‘moral therapy’ for the chronically homesick, which included early forms of talk therapy and rehabilitation rather than physical punishment. In contrast to Hofer, the nostalgia disease was re-conceptualised from a longing for space to a longing for a different time, a temporary teething problem for these pays-bound future subjects of the French republican state and its creed of universal moral progress.

Is the feeling of nostalgia a sign of who we really are or is it an impostor inside ourselves?

Rather than simply dismiss Hofer as outdated medical science, I think the historical consequences of his invention and diagnoses of nostalgia have shaped an important way of thinking about human desire, which aligns with that of cosmic horror. The very etymology of Hofer’s term ‘nostalgia’ raises more questions than answers – just where exactly can we neurologically or psychologically determine this correlation drawn between, on the one hand, nostos – an idea of homeland, and algos – a physical pain? This gap between our bodily aches and the ideal object opens up the horror of a fundamental emptiness of the human, that even our most profound pains and longings come from ‘outside’, as experienced by the melancholic Lionel Wallace in the H G Wells short story ‘The Door in the Wall’ (1906):

The fact is – it isn’t a case of ghosts or apparitions – but – it’s an odd thing to tell of, Redmond – I am haunted. I am haunted by something – that rather takes the light out of things, that fills me with longings…’

So which is it? Is nostalgia when we are at our most authentic and meaningful as feeling human beings? Or does nostalgia give an unsettling glimpse into our inner emptiness – our bodies moved by blind, alien passions? Is the feeling of nostalgia a sign of who we really are, or is it, as early modern physicians and sci-fi authors hold, an impostor inside ourselves? I think to even begin to answer this question we should take the cue of Hofer’s original concept and add a twist of cosmic horror. We should depersonalise nostalgia from a discreet, private matter of individual dreamers into a wider historical and philosophical problem of what longing means and how it feels today.