Architecture is physical, tangible and material. It is concrete, steel and glass. It is wood, brick and stone. It shelters and protects us by partitioning the vast expanses of physical space. At its core, architecture exists and operates in the outside world. What could it possibly say about our inner worlds? For Carl Jung, everything.

Throughout his life, until he died in 1961, Jung used architecture as a conceptual tool to study the structure of the human psyche. In fact, it was Jung’s dream of a multistorey house that helped him develop his idea of the collective unconscious. His exploration of this dream house proved so profound that Jung began to understand himself as a kind of architect. In the early 20th century, he designed two homes along the shores of Lake Zurich, not only to accommodate his daily needs but also to articulate the dimensions of his conscious and unconscious mind. Though now overshadowed by the enduring influence of his writings, these homes were fundamental to his work and life. For Jung, the unconscious could be understood only partially through words, feelings, dreams or theories. It also required a presence in physical space – a structure that partitions the vastness of the outside world. In many ways, architecture was at the heart of 20th-century psychoanalysis. For Jung, our inner worlds are unthinkable without it.

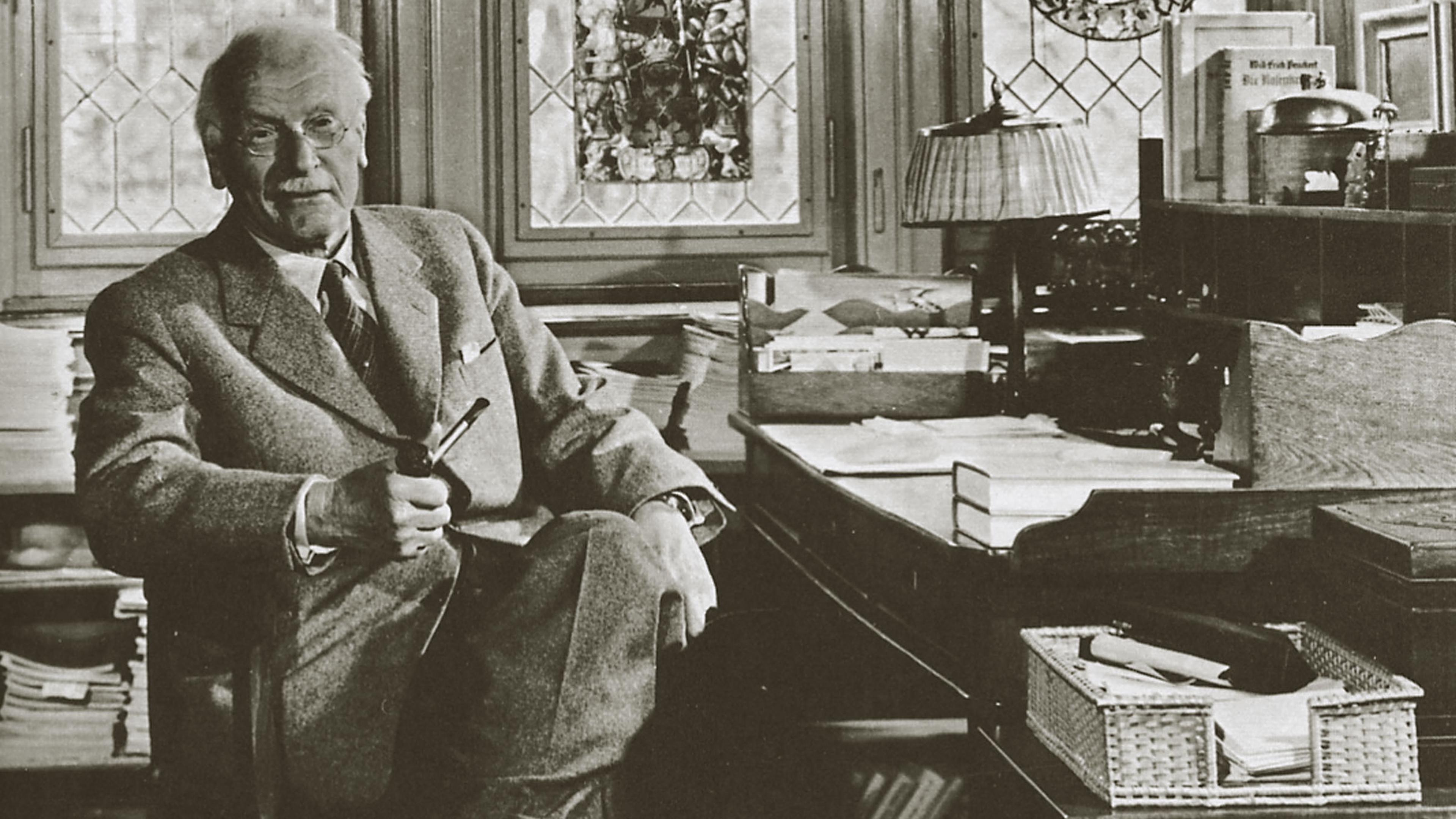

Carl Jung’s house in Küsnacht. Courtesy Wikipedia

Jung’s first house came to him during a dream in 1909. While travelling through the United States on a lecture tour with his fellow psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud, Jung dreamt he was in the salon of a two-storey house. The room was furnished with antique pieces of furniture and paintings hung on the walls. While exploring the salon, he found a set of stairs that led down to a basement. Everything appeared much older on this lower level. The furnishings and red-brick floors looked medieval. Eventually, he found a heavy door that opened onto a stone stairway leading down to an ancient, vaulted room. The walls and floor were made from stone slabs and bricks dating back to the Roman era. And attached to one of these slabs on the ground he found a metal ring. Pulling the ring, and lifting the slab, revealed yet another stairway leading further below. Following the narrow staircase down to the lowest level of the house, Jung arrived in a cave cut into bedrock. Thick dust blanketed the ground upon which bones and broken pottery were scattered as if they were the remains of a prehistoric culture. In the dust, Jung found two skulls half-disintegrated. Then he awoke.

For the rest of his life, Jung revisited this dream house to articulate his ideas about the structure of the human psyche. The salon represented ego-consciousness, the space we inhabit most often and populate with our best objects – the things we want others to see. But this floor is built upon older layers, each one representing significant epochs of intellectual history: medieval, Roman and Greek, and all the way back to prehistory. Jung interpreted the lowest level of the house to mean that all historical knowledge was founded on our primal roots. In other words, the architecture of the dream house showed Jung that we all, regardless of what we consciously believe, share a common set of unconscious, prehistoric beliefs. Jung termed this layer of the psyche the ‘collective unconscious’ and considered it the deepest core of humanity. In his autobiographical book Memories, Dreams, Reflections, first published in German in 1961, he wrote:

My dream thus constituted a kind of structural diagram of the human psyche; it postulated something of an altogether impersonal nature underlying that psyche. It ‘clicked,’ as the English have it – and the dream became for me a guiding image … It was my first inkling of a collective a priori beneath the personal psyche.

The collective unconscious, inspired by an architectural dream, proved to be one of Jung’s most influential concepts. According to Jung, the parts of ourselves we are conscious of – parts that together form our ego-consciousness – are influenced by pre-existing images and myths, which Jung called ‘archetypes’. These include archetypes of the wise old man, the great mother, the tree of life, eternity, and the sacred. Jung believed that these pre-existing, ancient foundations for thought were powerful enough to reroute and affect our conscious processes even today, including our notions of the self. Populating the collective unconscious, they provide a universal lower level through which humans understand the world around them.

The entrance to Carl Jung’s Küsnacht house. Courtesy Wikipedia

Though many of the ideas that Jung and Freud developed in the early 20th century were not founded on empirical science (and were often expressed using invented terms without objective definitions, making them impossible to falsify using the scientific method), their general theory of the unconscious has endured. More than a century later, the impact of Jung’s ideas about the collective unconscious can still be felt through popular conceptions of the unconscious mind and a demand for psychoanalytic therapies. Many people around the world continue to receive help from psychotherapists who use the concept of the unconscious mind to explain latent associations affecting behaviour. What’s more, Jung’s ideas about the collective unconscious and archetypes remain helpful for explaining the recurrence of common cultural narratives in popular novels, movies and even political campaigns, such as our affinity toward hero narratives or our support toward strongmen politicians. And all because of an architectural experience that came to Jung in a dream.

The dream house showed Jung that architecture could be a conceptual tool for understanding the structure of the human psyche. And perhaps it should come as no surprise. For in 1908, in the year before his dream, Jung had taken on the role of architect with the help of his architect cousin, Ernst Robert Fiechter, by designing a house for his family on the shores of Lake Zurich in the Swiss town of Küsnacht near the city of Zurich. Large and imposing, and still standing today, the exterior of Jung’s Küsnacht house resembles a castle. The building itself is pushed to the lake’s edge and features a large, prim garden as a front yard. Visitors walk a straight pathway to the front door, which is connected to a stately, three-storey watchtower that oversees all who enter. Jung designed the interior spaces for the most important aspects of his personal and professional lives. He built a large library full of books and an enclosed office space with stained glass windows blocking all views outside so he could focus on his work. At his Küsnacht home, Jung raised his family, consulted patients, and entertained guests. It accommodated his needs as a busy professional and father. It reflected his unified sense of self – right up until his identity began to break in two.

In 1913, Jung began to experience hallucinations and hear voices. At times, these experiences intensified into what we might today call ‘psychotic episodes’. Not one to shy away from the darker aspects of the mind, Jung searched these mental disturbances for meaning. During the next six years, he induced hallucinations through a process he called ‘active imagination’ and, like a cartographer of the New World, described everything he saw in notebooks. Jung eventually compiled his notes into a massive manuscript he titled The Red Book. Part personal manifesto, part Homeric epic, The Red Book describes Jung’s journey through the shifting dreamscapes of his unconscious mind as he reckons with archetypes, religious symbols, and ancient figures. In one passage, Jung gets into a shouting match with his soul. In another, he wrestles with the creative benefits of madness. It was a troubled and prolific time. It was a period Jung later referred to as his ‘confrontation with the unconscious’. And this period, too, would eventually have its own architecture: a third house.

Jung’s two houses on the shores of Lake Zurich represent the two aspects of his mind

Something fundamental changed in Jung following the period that brought about The Red Book. He created a wellspring of work that he would revisit for the rest of his life. It also triggered changes in his living conditions. Although the bulk of Jung’s active imaginations took place at his home in Küsnacht, he needed to escape the public-facing formalities and analytical composition of that house – at least periodically. So, in 1923, he designed another home in the town of Bollingen, around 30 kilometres beyond Küsnacht, nearly as far from Zurich as you can go along the lake shore. Jung visited his Bollingen house, which he called the ‘Tower’, to take refuge from the public, isolating himself to continue his engagement with his unconscious.

The Tower at Bollingen on Lake Zurich. Courtesy Wikipedia

From the outside, it is difficult to make sense of Bollingen’s composition. Unlike the house in Küsnacht, which greets visitors with a long garden and watchtower, Bollingen’s front entrance is a stone wall with a thick, wooden door. There are four towers, each with unique proportions, staggered around a courtyard. There are no clear indications of where the kitchen, living room or bedrooms might be, if they are there at all. While Küsnacht’s design is logical and resolved, Bollingen’s appears odd and chaotic. Its form emerged as Jung built additions to the house in multiple stages over the span of more than a decade. The first structure was a primitive, circular one-storey dwelling with a fireplace in the centre. Then, a new wing was built. Next, a larger tower. Each time, Jung would connect new structures to old ones, like mandala arcs. These additional constructions were not triggered by financial windfalls. Rather, Jung built new structures following major life events. After the death of his mother, he bought the land on which the house would be built. Following the death of his wife, he added a second floor with expansive views of the lake. As new dimensions were added to his personality, so too were dimensions added to his house in Bollingen. The sum of the building was a symbol of his return to psychic wholeness:

Words and paper, however, did not seem real enough to me; something more was needed. I had to achieve a kind of representation in stone of my innermost thoughts and of the knowledge I had acquired. Or, to put it another way, I had to make a confession of faith in stone. That was the beginning of the ‘Tower’, the house I built for myself at Bollingen.

Together, Jung’s two houses on the shores of Lake Zurich represent the two aspects of his mind: the conscious and the unconscious. His home at Küsnacht accommodated his ego-driven pursuits, including raising a family, operating a business, and putting on a facade for the public. His house in Bollingen, in contrast, was a space for his unconscious mind. It was primitive and secluded, with a circular composition that protected a private interior from the public. Bollingen was also a living entity that grew as Jung’s personality grew. New additions were added following major life events, giving form to Jung’s psychic development.

Doing so was an act of existential necessity. It helped Jung achieve psychic wholeness. Just as the goal of psychotherapy is to integrate unconscious content with the conscious mind to resolve mental conflicts, Jung used architecture as a tool to represent his psyche in physical space, to organise the different versions of himself, and pull himself out of mental illness. It was a tool that came to him in 1909, its possibilities revealed as he descended the stairways of a dream house and entered the dust-covered floor of the collective unconscious. It’s also a tool that remains available today. For those of us who have lost insight into our own unconscious, Jung’s approach to architecture is a provocation: how are we creating spaces for the forgotten dimensions of our minds?