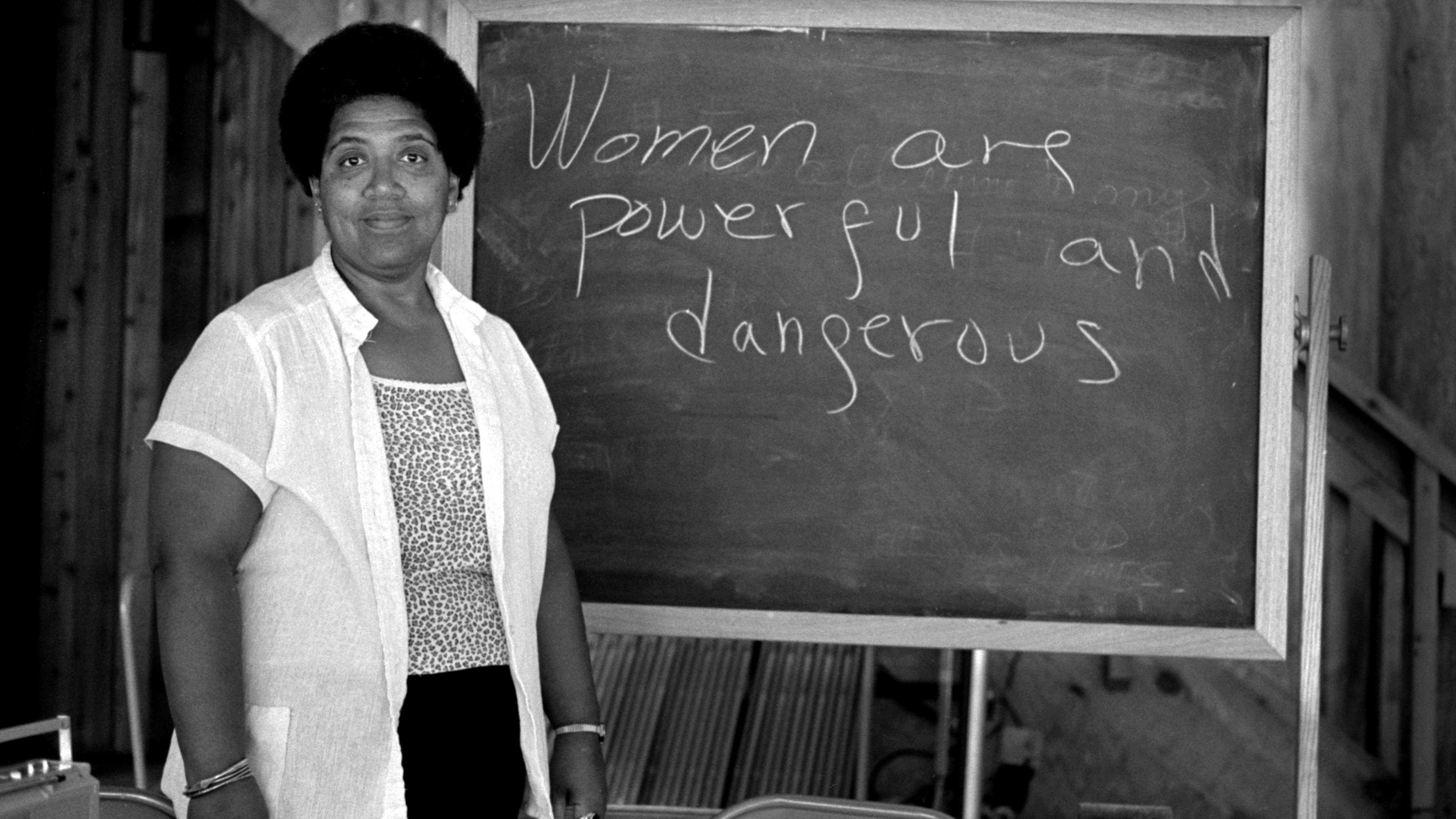

The feminist poet and scholar Audre Lorde left a legacy that my generation, women, people of colour and members of the LGBTQ community have widely and wisely embraced. And we still can’t get enough of her. When a name can be cited without reference to their title and still get respect, or when you use only their surname (even in niche spaces) and still people know who you are talking about, then you know that a legacy has not been simply left, but it lives.

Born Audrey Geraldine Lorde in 1934 in Harlem, New York, Lorde died at the age of 58 after living for 14 years with cancer. She was a complex figure, who boldly described herself as ‘a Black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet’. Her writings on race, sexism and emotions offer insight into what keeps us bound despite our best efforts. Yet her accusatory verse and prose do not simply leave us stuck in shame. Rather, they allow us to envision a better future, and they move us to engage in action to shape a new world.

Lorde, like many of us, was concerned with leaving a legacy. She was convinced that ‘nobody will attend my work with the passionate dare and precision it deserves and needs until I am dead.’ Her writings did become well known in her lifetime and they still resonate today.

Her biographer Alexis De Veaux writes that Lorde ‘connected women to a knowledge of themselves, and to other women as sister images of the self.’ In a review of her essay collection A Burst of Light (1988), the poet Cheryl Clarke wrote that:

Lorde’s work is a neighbour I’ve grown up with, who can always be counted on for honest talk, to rescue me when I’ve forgotten the key to my own house, to go with me to a tenants or town meeting, a community festival.

Adamant that she didn’t write theory, Lorde instead chose to embrace ‘poet’ as her literary title. But despite Lorde’s own thoughts, Nancy Bereano – the original editor of Lorde’s essay collection Sister Outsider (1984) – was right to conclude that ‘Lorde’s voice is central to the development of contemporary feminist theory. She is at the cutting edge of consciousness.’ I agree!

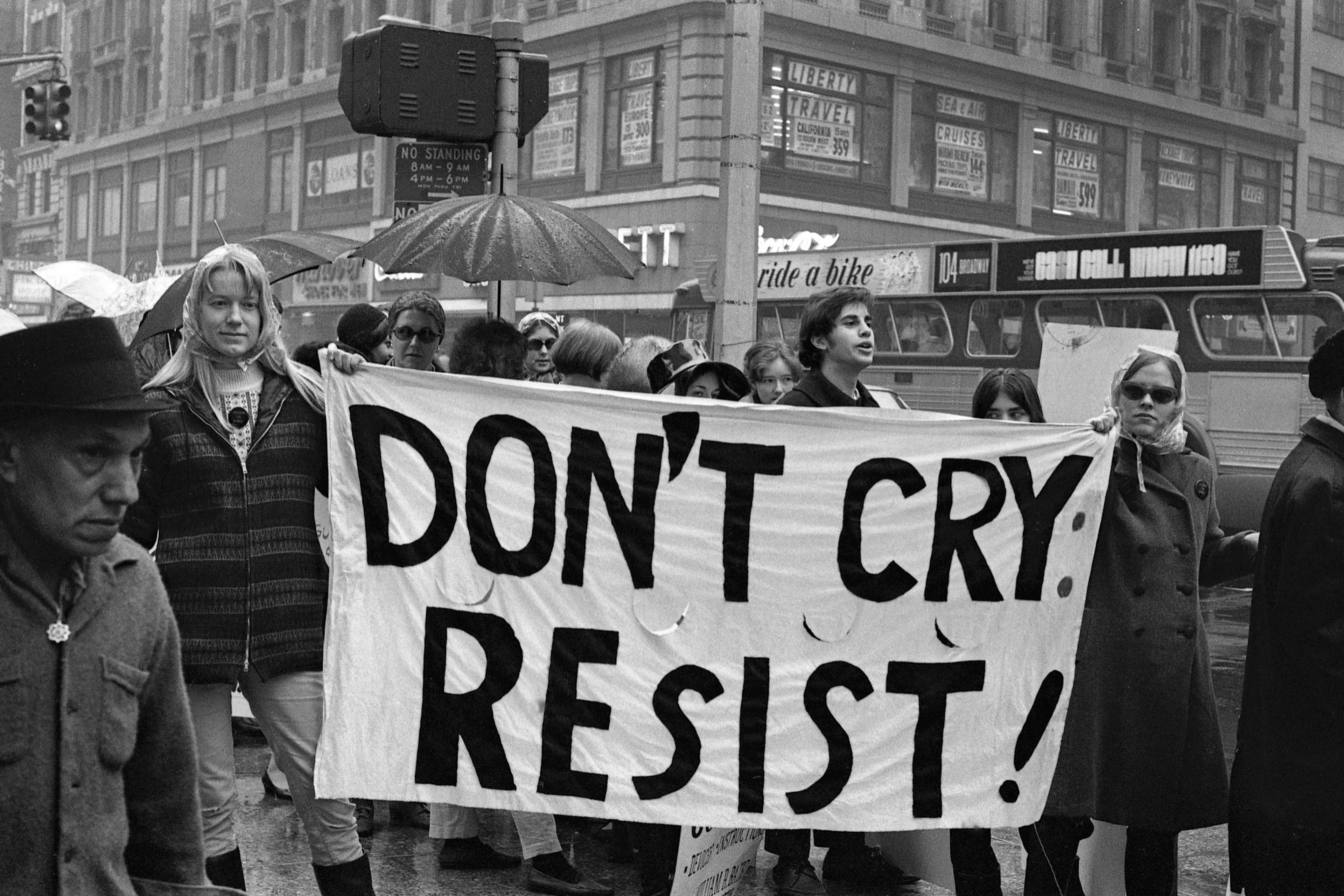

I experienced such thinking upon my first reading of her essay ‘The Uses of Anger’ (1981). I discovered it in 2012 while reading philosophy journal articles about emotions. I noticed that feminist philosophers were taking Lorde seriously as a theorist, and drawing inspiration from her argument that anger was epistemically and practically useful, particularly in a patriarchal society that teaches women not to be angry, and punishes them when they express rage. Lorde was one of the first feminist thinkers to attempt to take the shame away from being angry in response to racism and sexism. In the essay, Lorde teaches us that anger at racism is appropriate, loaded with energy and information. She also succeeds at explaining the political and existential import of anger, and boldly challenges readers to contest the oppressive conditions that give rise to it, as opposed to being defensive and resistant to anger.

The essay has had such an impact on our present-day thinking that writing any kind of work about anger without engaging with Lorde’s essay on the subject is an intellectual crime and an unfortunate tragedy. So, it’s not surprising that recent books on anger and other political emotions in response to the Me Too movement and the Movement for Black Lives reference her work. They include Soraya Chemaly’s Rage Becomes Her (2018), Rebecca Traister’s Good and Mad (2018), Katie Stockdale’s Hope Under Oppression (2021) and Brittney Cooper’s Eloquent Rage (2018). In my own book, The Case for Rage (2021), I give an account of antiracist anger, and I refer to it as ‘Lordean rage’ to pay tribute but also give credit to the ways in which Lorde has helped me rethink this emotion.

But ‘The Uses of Anger’ isn’t the only work of Lorde’s that has impacted feminist and antiracist thinking. Both Sister Outsider and A Burst of Light as well as The Cancer Journals (1980) contain essays that have helped generations of scholars, artists and activists rethink care, the erotic, difference and solidarity. It’s within these themes that I think Lorde has left an invaluable contribution.

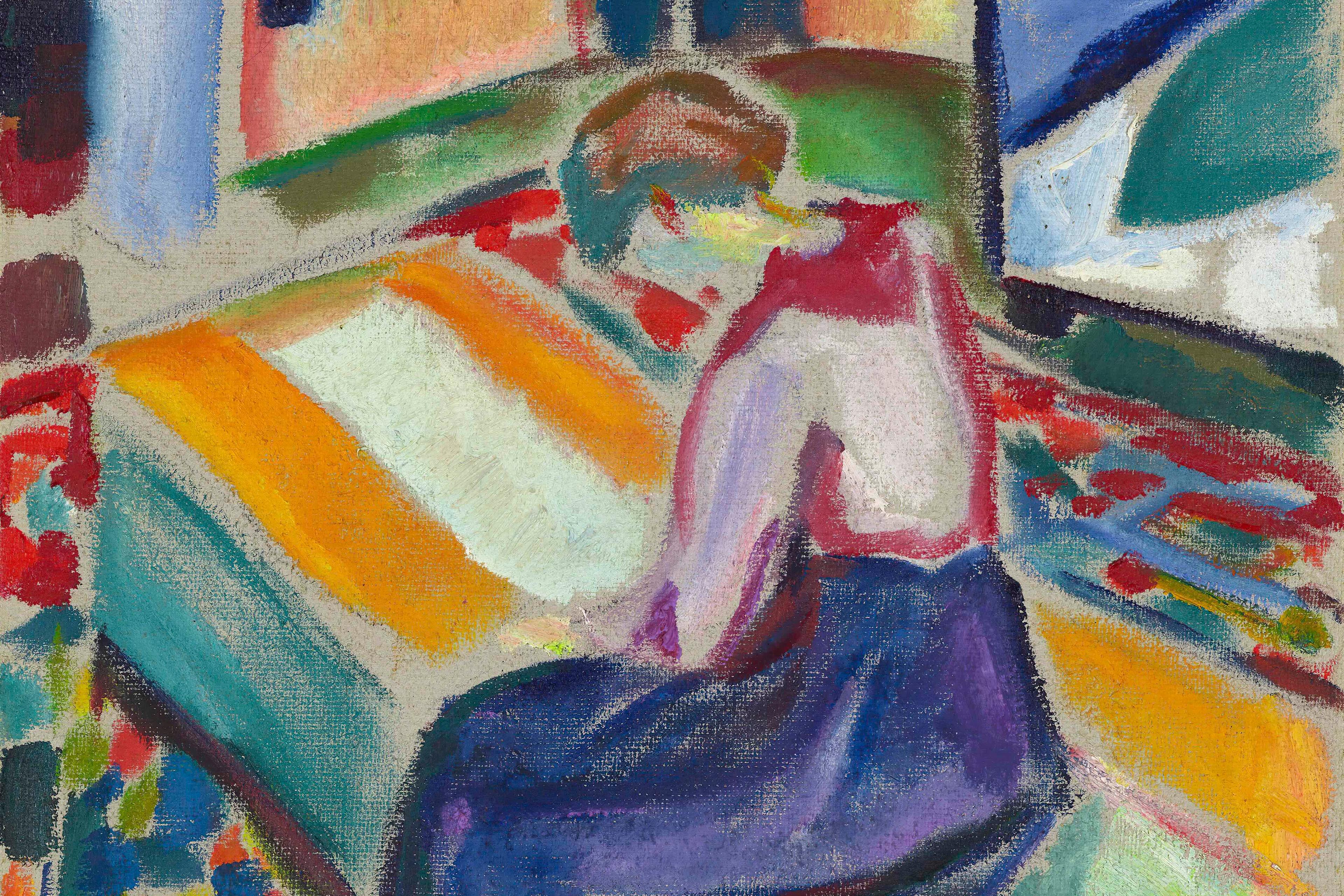

Lorde’s treatment of the erotic is in many ways similar to her re-evaluation of anger. In response to it, Roxane Gay writes in her introduction to a new collection of Lorde’s selected works that ‘what is so remarkable about Lorde’s writing – [is] how she encourages women to understand weaknesses as strengths.’ Lorde helps us see that the erotic is a strength, and defines it as:

creative energy empowered [and] … those physical, emotional, and psychic expressions of what is deepest and strongest and richest within each of us, being shared: the passions of love, in its deepest meanings.

The erotic is a source of knowledge. It helps us develop our capacity for joy. We can see this joy as we move to music or work in our gardens. The erotic also allows us to share that joy with others, the effect of which is that it ‘lessens the threat of their difference’. The erotic allows us to feel ‘deeply all the aspects of our lives’. This allows us not to settle for the safe or convenient; suffering, powerlessness, or numbness. When we are in touch with this feeling, Lorde claims, ‘we touch our most profoundly creative source [and] we do that which is female and self-affirming in the face of racist, patriarchal, and anti-erotic society.’ It’s for these reasons that the queer thinker Nikki Young writes that ‘Lorde’s erotic innovation has established itself as a political, social, and academic tool of deconstruction, subversion, and imagination.’

While the rhetoric of self-care is currently being used to promote everything from beauty products to vacations, Lorde was one of the first thinkers to theorise self-care as a necessary political act. She writes in A Burst of Light – a collection made up of notes she writes while she discovers she has cancer – that ‘caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation and that is an act of political warfare.’ As she defined it, care wasn’t a reference to a capitalistic, treat-yourself philosophy but a survival imperative that could take place only within a community. The need for care was due to fighting against injustice, overextending and overworking oneself to exist, as well as bringing about change. It was a remedy to help us handle fatigue and burnout so that we can live and fight another day.

Self-care wasn’t just limited to the care we extend to ourselves. For Lorde, it also involved the fears we conquer and the monstrous things we courageously face. Her Cancer Journals – I proudly own a first edition – was birthed out of, and intended to be used in, the service of self-care. The Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Alice Walker writes that The Cancer Journals ‘has taken away some of my fear of cancer, my fear of incompleteness, my fear of difference.’ The Journal continues, for many, to serve Lorde’s original intent: ‘May these words serve as encouragement for other women to speak and to act out of our experiences with cancer and with other threats of death, for silence has never brought us anything of worth.’ This ‘re-evaluation’ of care has helped many prioritise their wellbeing and the wellbeing of others, not as a distraction from, but as a contribution to political and social change.

Before the word ‘intersectionality’ became part of our academic and popular parlance, Lorde was thinking about difference and people’s tendency to ignore it – particularly when it came to endeavours requiring solidarity. However, Lorde calls our attention to the ways in which embracing our differences (of class, sex, race, etc) allows us to see people as whole persons with complexities, and thus doesn’t hinder but rather helps build solidarity. She encourages us not to ignore difference:

It is not our differences which separate women, but our reluctance to recognise those differences and to deal effectively with the distortions which have resulted from the ignoring and misnaming of those differences.

She believes that the recognition can help us ‘devise ways to use each others’ difference to enrich our visions and our joint struggles.’

It wasn’t difference, she believed, that was getting in the way of solidarity efforts, but rather racism and sexism within oppressive communities. She reminds those who are dedicated to transforming our world for the better that ‘the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.’ In other words, the destructive tactics, and methods of oppression (in this context principally racism and sexism) that have been used historically by powerful white men to dominate others cannot be the means to gain freedom for oppressed communities.

It’s for this reason that she calls out the ageism, homophobia and heterosexism of Black men; the self-hatred of Black women; and the racism of white feminists. She cautions that the master’s tools will ‘never enable us to bring about genuine change’ and she exhorts us to remember that ‘Divide and conquer in our world must become define and empower.’ It’s for this reason that I teach her essays in my ‘Race and Gender’ course every year. I do it to help my students think about solidarity and allyship, its hinderances and its importance. Lorde speaks in a way that my students understand and that they are challenged by. It’s a joy as an educator to hear them relate to her worries, hum to her insights, and think with her about solutions to endemic problems.

Gay is correct in noting that Lorde’s work ‘forges a space within which we can hold ourselves and each other accountable to both our needs and the greater good.’ When so much has changed since her death, but many social and political problems remain, Lorde has left a freedom manual – hidden within the pages of her poetry and essays – to help us navigate the times honestly, openly and responsibly. What a legacy!