I remember the first time I said the word ‘penis’ in a classroom. It was 12 years ago in Cairo. I was a young psychology teacher, not much older than the students I was teaching. I remember the feeling of trepidation that came over me as I uttered the word. The kind that makes your heart pound so loudly, you think everyone can hear. I also remember my students’ reactions as they stared at me in disbelief, not knowing if I actually said what I said. I remember the girls’ blushing and the boys’ muffled gasps. It was as if the word ‘penis’ had dropped the fig leaf to uncover our naked reality. An acknowledgment that we were biological beings, not merely suspended creatures vacillating between presence and an all-encompassing ennui. In a classroom filled with hormonal teenagers, uttering the word ‘penis’ disarmed the air of nonchalance that masked their vulnerability.

Now I am happy to report that I say ‘penis’ without even batting an eyelash. I even play a little game where I try to anticipate my students’ reactions. I try to guess who will flinch, which boys will instinctively close their parted legs as if the word is an attack on their masculinity, who will blush, and who will try to find this an opportunity for passing thinly veiled sexual innuendo into the conversation. Their reactions are quite telling and, since the course focuses on personality, I find this a great opportunity to peer into theirs. I haven’t been accused of corrupting the youth yet, but you never know!

The discourse centred on male genitalia is usually presented to my class while introducing Sigmund Freud’s psychosexual theory. In this theory, Freud divides human psychic development into stages based on a series of physiological changes. The Phallic stage, which literally means penis stage, is the only time Freud addresses female psychic development in his theory. He states that girls from the age of four to six experience what he calls ‘penis envy’ – when girls wish to become boys.

Having experienced the desire to become a boy during my childhood, I always do a quick poll. I ask my female students how many of them experienced the same desire. I have come to notice that the number of girls who shared my desire has been diminishing over the years.

The root of this trans-generational desire is then investigated. Does it emanate from an inherent physiological deficiency that girls experience (ie, Freud’s interpretation) or is it due to cumbersome social forces that impose feelings of inferiority upon young girls? The investigation is usually guided by the theories of the feminist psychologist Karen Horney (1885-1952) contra Freud.

Horney was a prominent psychoanalyst who rose to fame through postulating an antithetical proposition to Freud’s psychosexual theory and particularly to penis envy. She believed that Freud failed to account for the true force underlying penis envy, and rejected his theory. Horney acknowledged that some girls do experience pervasive feelings of inferiority that might amount to a yearning to become boys. Nevertheless, she disagreed with Freud regarding the underlying reasons causing this rift. For Horney, the girls who want to be boys feel that way because of the social restrictions and stigma associated with being a girl. Their desire manifests itself in the embodied male, because he is independent, autonomous and free. Thus, penis envy can be understood as a masked yearning towards freedom in a society that failed to provide the vocabulary of freedom to young girls, so they subsume their aspiration in the societal totem of freedom: ie, boys.

As a woman, I find myself leaning towards Horney’s interpretation more than Freud’s. Perhaps because Horney’s explanation emanates from her experience as someone who suffered from the mere fact that she was a woman.

There is a question that I’ve come to ask my class every single year. How did a psychoanalyst’s life, or certain events in her life, shape her theories? I know that, ultimately, how a person behaved in private shouldn’t have any bearing on their scientific rigour. Yet, in a field like psychology, and especially in personality psychology, a discipline where psychologists claim to have unadulterated insight into the human psyche specifically, and the human condition in general, it becomes difficult to divorce a practitioner’s lived experience from their theoretical paradigm. If we apply this question to Horney, we could hopefully witness the formative experiences that shaped her theories.

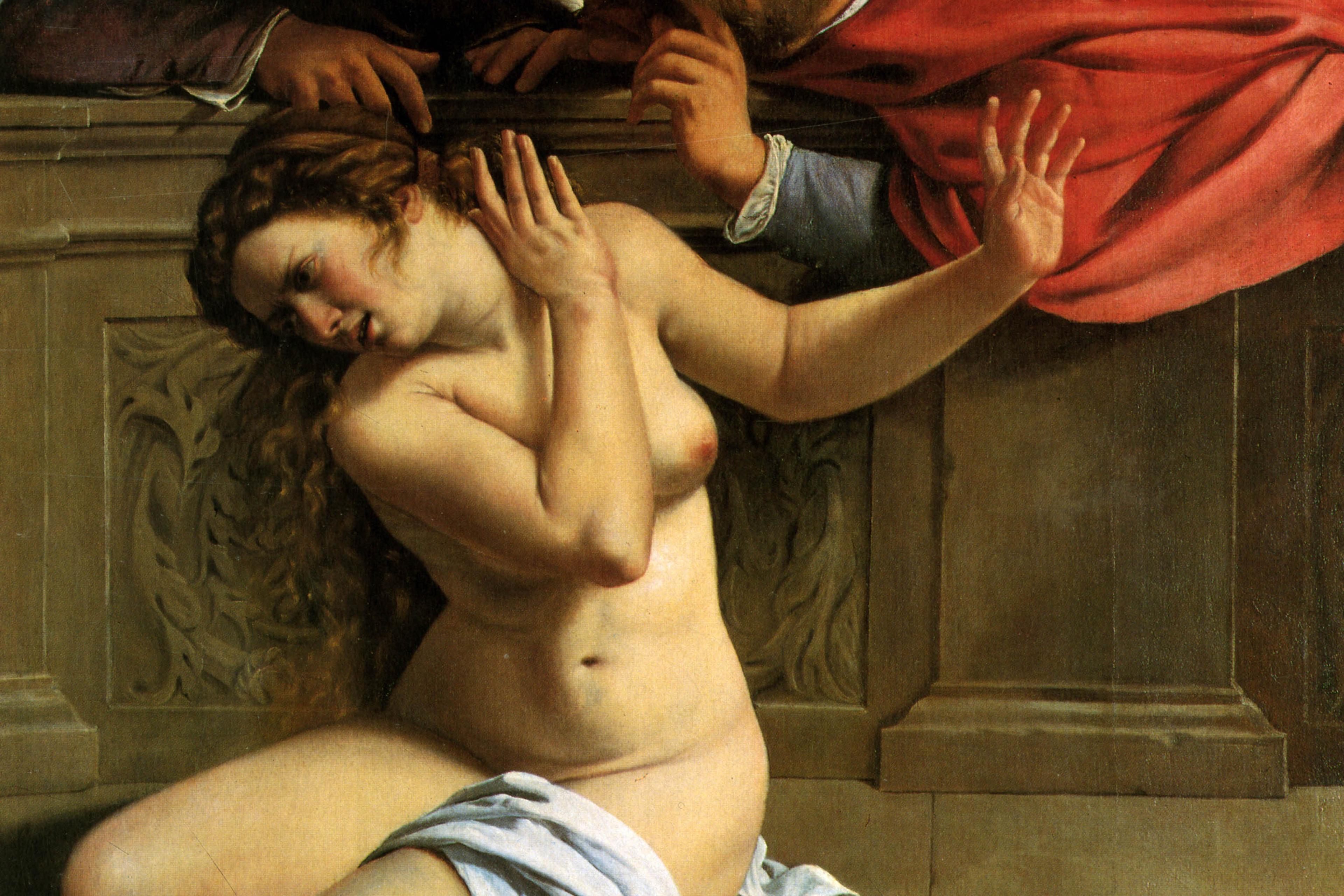

Karen Horney in 1953. Photo by Bettmann/Getty

Horney grew up in a household where masculine superiority over the feminine was a heuristic concept grounded in a particular Biblical interpretation. Her father believed that a woman naturally belongs to the private realm. Accordingly, a girl’s education and upbringing should be an effort to domesticate her in preparation for her role as a homemaker. The brilliant and rebellious young Karen found in her father’s denial of her uniqueness ample motivation for her excellence. It is within this static masculine/feminine milieu that Horney pursued her life’s work, trying to provide evidence that femininity was not innately submissive. I would further argue that Horney’s intellectual paradigm wasn’t merely created and guided by the feminine/masculine dichotomy – rather, her views were held captive by it to the extent that she was unable to move beyond it.

Though Horney’s fame is mainly attributed to rejecting penis envy, her psychological corpus extends beyond this theory of Freud’s. Horney studied neurosis extensively, grounding its roots in early childhood interaction with parents. The quality of these interactions, for Horney, shapes self-perception and ultimately our relationship with our selves. She also identified the different neurotic coping mechanisms that can aid psychoanalysts in identifying and helping patients who exhibit this behaviour. Horney’s work sheds light on the importance of early parent/child relations in the construction of a healthy sense of self, beyond the immediate biological necessity and mythological inevitability espoused by Freud. Her theories can be viewed as emanating from a matriarchal worldview that privileges warmth and love as the primary indicators of a healthy adult life. Freud’s theories created a competitive cosmos filled with trials and tribulations where a human being must prove their worth. Horney’s theories created a cosmos where a human being is given, through care, the tools that can enable them to overcome adversity. Whether her intellectual views were practised in her life is another question.

Horney had a troubled relationship with her mother, not to mention her father. If one were to survey Horney’s life, one wouldn’t be able to escape the feeling that she had a sense of compulsion to prove her father wrong through her achievements. Once her father was no longer a factor in her life, she found a worthy opponent for herself in the father of psychoanalysis: ie, Freud.

And don’t get me wrong, I truly believe that Freud’s psychosexual theory fails to provide any allowances for female psychological development. He addresses psychological changes fuelled by biological occurrences – ie, breast feeding, toilet training, puberty – without addressing female biology – ie, pregnancy, menopause, breast feeding – from the other side, and how it can impact women’s psyche, even though most of his patients were women. In that respect, Horney offered a much-needed insight into human development that is anchored within familial connections. Hers was a counter-narrative to the inevitability of the biologically necessitated fixations that were offered by Freud. Ultimately, that care and love are capable of healing what has been damaged, and can pre-emptively prevent damage. Horney created an intimate landscape for development where a relationship between parent and child becomes the initial representation of self and other. Within this matriarchal cosmos that was theoretically thought up by Horney, a child is allowed to make mistakes that are rectified and guided by parental love. It is through this force of love that the child learns that mistakes do not subsume who she is. Horney’s cosmos is founded upon delivering a child from perfectionist or destructive tendencies to a balanced form of self, a real self that holds the core for individual self-realisation and the potential for future success.

Nevertheless, Horney’s personal life was turbulent. She had a series of depressions, an ambivalent relationship to motherhood, and a great many romantic affairs. Her work, her theories were her true passion. And, almost in every work, she mentions Freud. Though it was essential to discuss Freud’s theory, I can’t shake away the notion that her discussion of Freud’s work was an attempt to seek his, or her father’s, validation. This pursuit prevented her from embracing her matriarchal views and living them. Horney was a genius, who I believe trapped herself in a Freudian cosmos instead of living in the one she created herself.