One of the most powerful effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, after its terrible toll on human life, has been on our liberty. Around the world, people’s movements have been severely curtailed, tracked and monitored. This has had an impact on our abilities to earn a living, study and even be with loved ones at the end of their lives. Freedom, it seems, is one of this virus’s biggest casualties.

But an article by Jean-Paul Sartre for The Atlantic in 1944 makes me question whether this is a straightforward tale of loss. The French philosopher summed up his thesis in the line: ‘Never were we freer than under the German occupation.’ Sartre’s core insight was that it is only when we are physically stopped from acting that we fully realise the true extent and nature of our freedom. If he is right, then the pandemic is an opportunity to relearn what it means to be free.

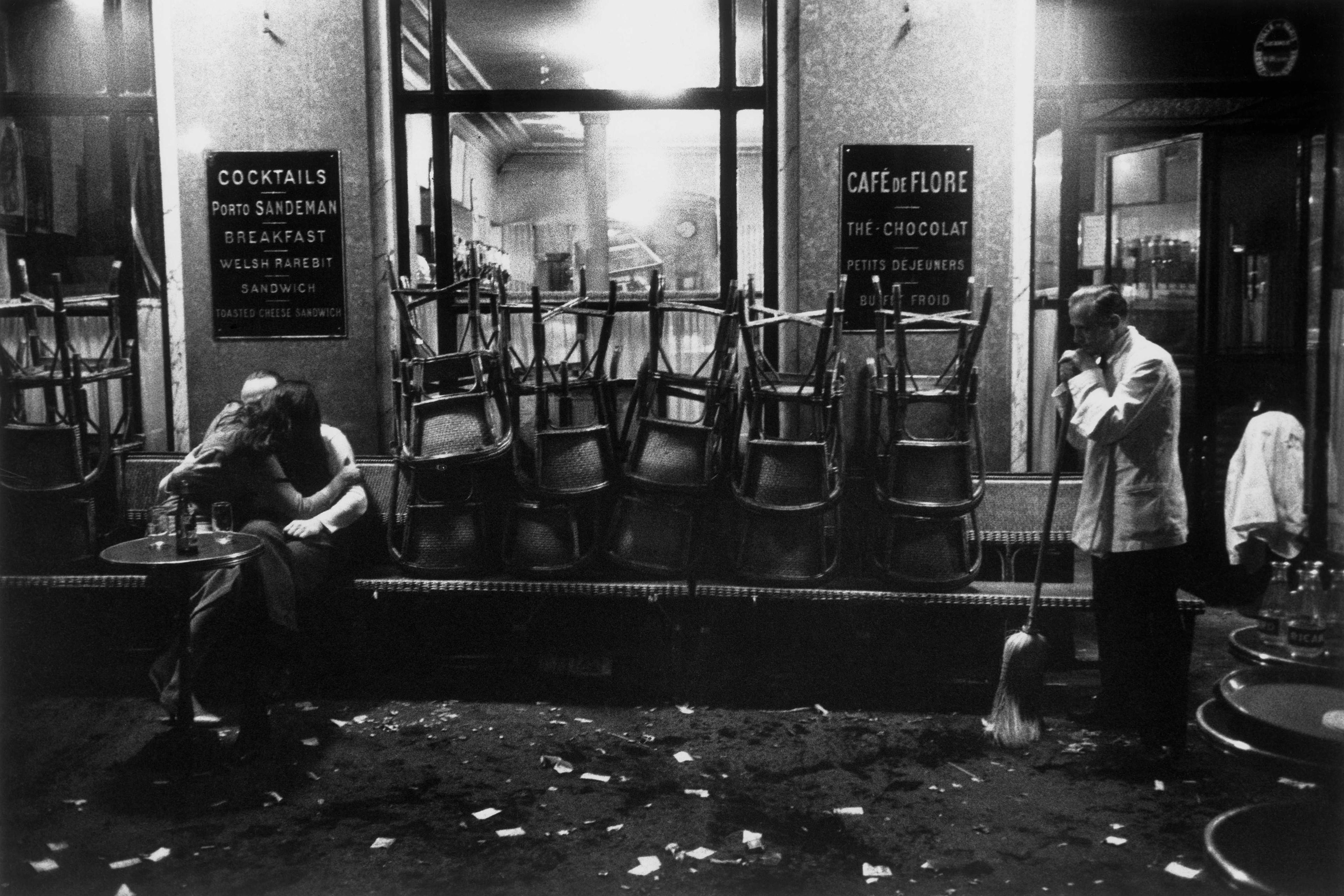

Of course, our situation is not nearly as extreme as it was for the French under occupation, who, as Sartre said, ‘had lost all our rights, beginning with the right to talk’. Still, like most of us, I have at times found myself unable to do almost everything I had taken for granted. During the strictest lockdown period, nights out at theatres, concert halls and cinemas were cancelled. I couldn’t go for a walk in the countryside, relax in a bar or restaurant, sit on a park bench, visit anyone, even leave my home more than once a day.

Yet I haven’t been the only one to experience this as, at least in part, a liberation. It drove home to me how so many of the things I habitually ‘chose’ to do I did simply because they were there or because I had got into the habit of doing them. Others have noticed how much they were just going along with what other people were doing. In a fast-paced consumer society with endless options, we are easily bounced around by our whims, manipulated by advertisers and marketers. Very little of what we do every day is the result of a considered decision. Being able to do what we want without constraint, but also without thought, is the lowest and least valuable form of freedom.

In lockdown, I learned that I missed much less about this old life than I would have thought. I was reminded how shallow many of our preferences really were. When my options shrunk and any activity required more planning, the choices I made became more authentic because they had to be more thought-through. This capacity for reflective decision-making is the highest and most valuable form of freedom a human being can have.

In short, the pandemic enables us to see more clearly the difference between the hollow freedom to act without impediment and the true freedom to act in accordance with our all-things-considered judgments. The American philosopher Harry Frankfurt in 1971 illuminated the difference with his distinction between the things that we simply want and the ones that, after consideration, we want to want. For instance, if I want a doughnut and eat it, I’m simply following my desires, the wants I find myself having at any given moment. But if, on reflection, I don’t want to eat junk food (or, at least, not often) then I have the capacity to veto these wants in the light of what I know I want to want. This kind of freedom requires self-restraint. A person without this capacity is not truly free but is what Frankfurt calls a ‘wanton’: a slave to his desires.

The consumer society encourages us to act like wantons. So when it is disrupted, by war or pandemic, so too is the lazy habit of acting on desire without proper reflection. Any time when our ability to act on impulse is severely restricted, we have the opportunity to break the habitual link between desire and actions, and question whether the desires we act on are the ones we endorse, all things considered.

The vital importance of our capacity for freedom is also made starker by the gravity of our circumstances. During the occupation, Sartre wrote:

At every instant we lived up to the full sense of this commonplace little phrase: ‘Man is mortal!’ And the choice that each of us made of his life and of his being was an authentic choice because it was made face to face with death …

In 1944, this was truer than today because many choices were literally life-and-death ones. Resistance fighters found themselves thinking ‘Rather death than …’ Today, few of our choices have such stark and immediate consequences. But the daily reminders of death force us to take seriously the choices we make, about our work, our relationships, our lifestyles. Many have discovered that they are living a life they never really chose, but merely drifted into. A new urgency screams at us that, unless we make a change, this will be our lot until we die, which could be sooner than we think.

So instead of following the path of least resistance, I’ve been trying to make more considered choices, which means saying ‘No’ more often and picking my projects more carefully. Many of us are now making hard choices, the most authentic ones we have made in years, to try to live a life more aligned with what we truly value, with what we want to want. Although the military metaphor of a war on the coronavirus is overused and often inapt, it works perfectly when applied to another of Sartre’s striking sentences: ‘The very cruelty of the enemy drove us to the extremities of this condition by forcing us to ask ourselves questions that one never considers in time of peace.’

Another line that resonates is ‘Total responsibility in total solitude – is this not the very definition of our liberty?’ For Sartre in 1944, the solitude was that of the underground resistance fighter, working alone for the common good. ‘In the depth of their solitude, it was the others that they were protecting, all the others …’ Our solitude in this pandemic is less extreme, as are the risks and sacrifices we’re called on to make. Still, the same essential moral insight applies. How we behave in ordinary life is a poor measure of our moral backbone, since we’re rarely called on to go above and beyond the call of duty or given the opportunity to break the social contract without penalty. Now, however, our socially isolated choices reveal our true colours.

People who have voluntarily worked at the frontline, risking their own lives, have shown their courage. Others who have rallied around to feed and shelter the most vulnerable instead of simply holing up at home have shown their compassion and care. On the other hand, those who have broken the rules merely for their own convenience have exposed their selfishness, and often a sense of privilege. Like most of us, I fall in between, showing that I am no hero but no villain either, just one of the many ordinarily decent people who are neither especially praiseworthy nor blameworthy.

The pandemic also teaches us about freedom in ways that go beyond Sartre’s discussion of the individual. Politically, using Isaiah Berlin’s distinction, we talk of the ‘negative liberty’ to go about our business without restraint, and the ‘positive liberty’ to do the things that give us the possibility to flourish and maximise our potential. For example, a society where there is no compulsory schooling gives parents the negative liberty to educate their children as they wish. But, generally speaking, this doesn’t give the child the positive liberty to have a decent education.

Over recent decades in the West, negative liberty has been in the ascendancy and positive liberty has been tarred with the brush of the nanny state. What we should have learned in 2020 is that without health services, effective regulation and sometimes strict rules, our negative freedom is useless and even sometimes destructive. Without state ‘interference’, many more lives would have been lost, jobs destroyed and businesses ruined.

We now have an opportunity to reset the balance between negative and positive liberty. There isn’t a trade-off between big government and personal freedom: many freedoms depend on the state for their very possibility. What the social scientists Neil and Barbara Gilbert in 1989 dubbed the ‘enabling state’ and the economist Mariana Mazzucato in 2013 called the ‘entrepreneurial state’ are essential for giving us the opportunity to realise the full potential of our freedom.

One final way in which we are waking up to our freedom is that our conception of what’s possible has been expanded. Hospitals can be built in weeks, not years; air quality can be improved almost overnight; governments can subsidise employment rather than just pay unemployment; private companies, such as food retailers, can be held accountable as public services and not just private enterprises. The Overton window has been flung wide open. More is possible than we imagined.

Freedom to act without a belief in the possibility to act is empty. Our eyes have been opened to more potential futures than we believed were available to us. The challenge is to respond to this opportunity without falling into naive utopianism or wishful thinking. Our realisation is not the simplistic belief that we have fewer constraints than we thought we had, but that the actual constraints we have are not the ones we believed them to be.

I am not equating the trials of living under Nazi occupation with living with the scourge of COVID-19. But despite the many and important differences, Sartre’s message of freedom in 1944 rings just as true today. Our primary experience is one of restriction, of loss of liberty. But, with thought and reflection, we can follow this with a renewed sense of what freedom really means, why it matters, and how we can use it to forge a better future. Perhaps we will soon look back and say, as Sartre did: ‘The circumstances, atrocious as they often were, finally made it possible for us to live, without pretence or false shame, the hectic and impossible existence that is known as the lot of man.’