Moving in silent desperation

Keeping an eye on the Holy Land

A hypothetical destination

Say, who is this walking man?

– from ‘Walking Man’ (1974) by James Taylor

Last year, New York City finally legalised jaywalking, which feels not only overdue but also oddly symbolic of the postmodern times we live in. It seems only fitting that it coincides with the one-year anniversary of California’s Freedom to Walk Act. For native New Yorkers like me, jaywalking was never about flouting the law; it has always been about culture, survival and autonomy.

Growing up in Afro-Caribbean East Flatbush, Brooklyn, crossing against the light – or mid-block – was a regular part of life. Our two-family, three-storey home was on a one-way street directly across from my six-storey, red-bricked grade school, P S 135. By the time I hit second grade, I was crossing on my own. No one I knew ever bothered waiting for the ‘walk’ signal. Crosswalks were for amateurs – those who needed the extra visibility or had the luxury of spare time. For the rest of us, crossing whenever and wherever we could was as common as the graffiti on subway cars in the 1970s.

It wasn’t until I moved to San Francisco in the mid-1990s that I learned that it was technically a crime in both coastal cities. Settling into Lower Pacific Heights – a mostly white neighbourhood with a bougie-bohemian vibe – I quickly intuited that the city’s liberal sensibilities did not extend to its street laws. I was also stunned by the blind obedience of my fellow pedestrians, who waited patiently at street corners, even when there were no cars coming for a full city block – adhering to the law as if it were a point of pride. I, on the other hand, felt a deep-rooted compulsion to skirt California’s jaywalking law. Ignoring honking drivers and visibly scandalised passersby, I continued my haughty scofflaw antics, relying on the instincts I had honed during my years of weaving through rush-hour crowds on the concourse level of the original World Trade Center.

Fast-forward to the mid-2000s and I’d moved to Los Angeles, where one’s car dictates their identity as much as their race, ethnicity or job. I drove a used burgundy 1990 Buick Regal, embodying the outsider perspective that came with being a Black gay man working as an office temp in the entertainment industry at places like Disney, LA Weekly and E! Networks. It felt fitting to be a queer outsider in my little Hollywood-adjacent neighbourhood but, unlike many Angelenos, I consistently took to walking the streets. Every so often, I even took the bus or the Metro to get around. Walking became my little act of defiance against the near-universal norm of driving everywhere.

Initially, I maintained my jaywalking habits, but a growing cognitive dissonance began tugging at me. The East Coast urgency I grew up in felt out of sync with the slower, more deliberate pace of California. I found unexpected bliss in waiting at street corners, which allowed for moments to breathe rather than racing around to check another task off my to-do list.

Even my own mid-block shenanigans started to feel unnecessary – almost juvenile. Eventually, my notion of jaywalking shifted from a badge of honour to something more nuanced. The act of crossing at the light was not merely about obeying the law – it was an acknowledgment of my evolving relationship with time. Eventually, I began to embrace the mellowed rhythm of my new life, fully aware that walking had become synonymous with freedom: a journey of daily discovery rather than a simple means of transportation. Or a way to get from one place to another.

Then, on one particularly fateful evening in Valley Stream, Long Island, while visiting my parents, everything changed, yet again. I was dressed in white pants on a brisk January evening – even though old-school fashion rules dictated not wearing them past Labor Day. But I didn’t care; I stepped into the crosswalk, feeling visible and safe. That confidence shattered when a black Hyundai Santa Fe veered into the intersection, striking me and throwing me onto the hood before I rolled to the ground.

Acts I once took for granted – standing, walking, sitting upright – felt Herculean

The world around me began to spin, blur and split as pain radiated down my spine. The last thing I remembered was trying to recall the car’s licence plate as the elderly female driver sped away. What followed was a rotating blur of healthcare providers, diagnostic tests, medical machinery sounds and eye-watering agony – all culminating in the news that I had sustained a herniated disc, requiring emergency spinal fusion surgery.

Rehabilitation was an arduous uphill climb that tested my resilience. I wore a bone stimulator device affixed to my neck around the clock, and faced gruelling physical therapy sessions with timed, repetitive tasks that felt eternal. Acts I once took for granted – standing, walking, sitting upright – felt Herculean. I was grappling with a limited range of motion and permanent disability, which morphed the freedom I had once equated with walking into an oppressive reminder of my condition.

Step by literal step, I had to redefine what walking meant to me. It moved from simply being a means of getting around to a metaphor for healing and acceptance. Walking had become imbued with meaning, allowing me to reflect and embrace the slower pace of life. My experience reshaped my understanding of movement; it was no longer a hurried pursuit but an expedition toward acceptance. Embracing this slower rhythm allowed me to appreciate the little victories in each day, as my relationship with crossing streets evolved into a deeper awareness of life’s fragility.

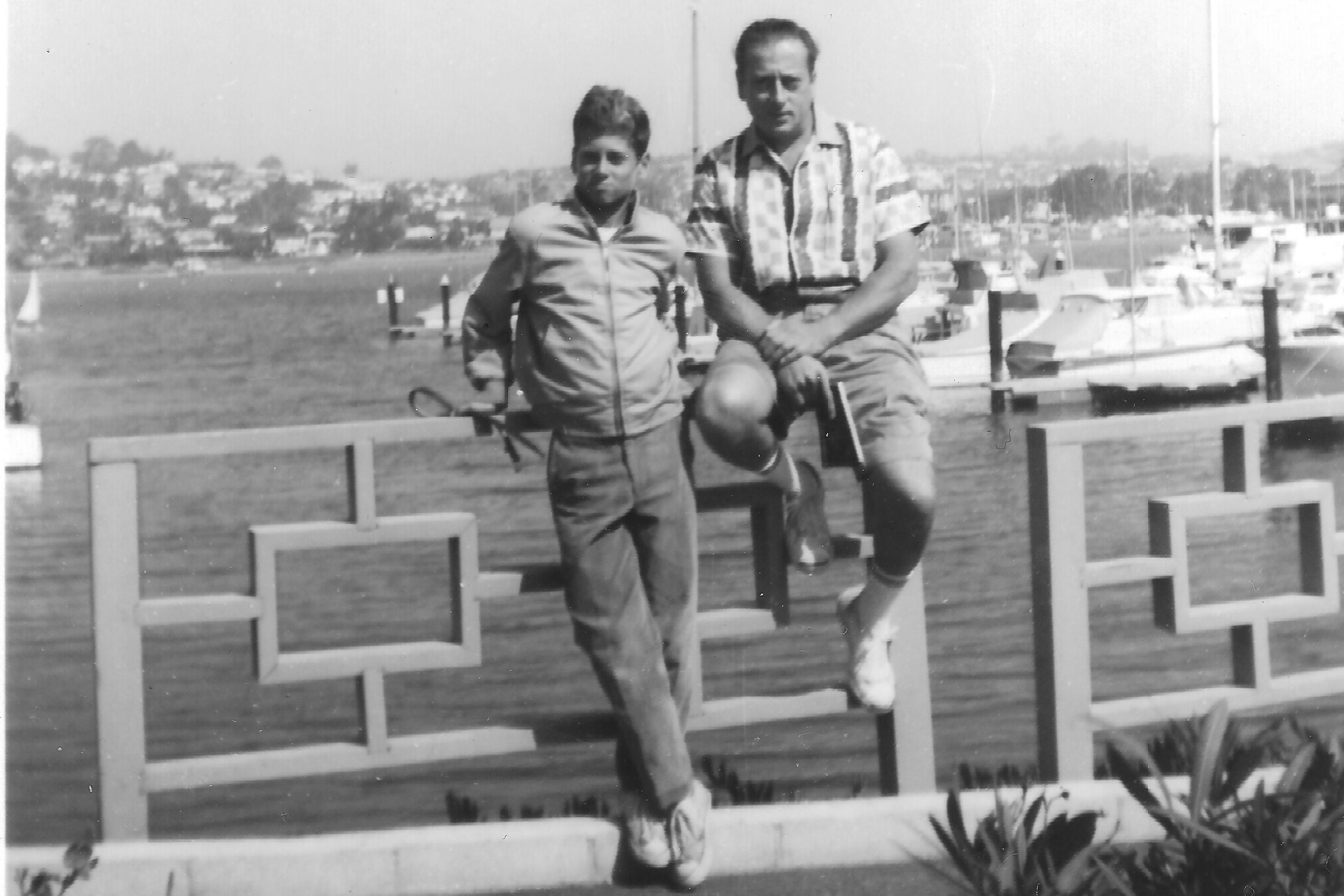

Speaking of relationships, earlier this year I ended up having to leave my beloved California life behind to move back to New York. My 90-year-old West Indian father, a US veteran with advanced dementia, needed more long-term, round-the-clock support than my mom and brother could provide. As part of our new ritual, I try to take him out for daily walks, weather permitting. Our usual route is to walk from one end of our long suburban block to the other, never cross the street – because, at his slow pace, he needs more time than the light gives – then back to the house.

With New York and California finally catching up to the long-accepted act of jaywalking, the practice feels less transgressive and more sentimental – like the relic of a bygone era. Though I still jaywalk every now and again, the steps I take these days are informed by the ones I’ve taken before. Now, I walk with a different level of responsibility in order to continue caring for Dad, whose care has also forced me to slow down, even amid New York’s frenzied pace.