There is a typical picture of childhood education that is probably accurate for most schools around the world: a classroom with a board, a teacher’s desk in the front, symmetrically aligned rows of student desks, colourful posters hanging on the walls. The teacher stands at the front of the classroom, writing on the board while explaining how to solve textbook problems. The children sit quietly (one hopes) and take it all in.

Today, there is an entire research field that is dedicated to figuring out how best to shift away from these typical school classrooms and traditional pedagogies to more engaging, effective and productive teaching methods. Researchers and educators conduct scientific studies to transform student learning, teacher pedagogies, learning environments and curricular materials to be more interactive, innovative, inspiring and inclusive. But the development of innovative pedagogies is not only a modern endeavour.

As in many other areas, we can trace the origin of these new teaching approaches back to ancient Greece, almost 2,500 years ago, in the earliest public institutions of higher education we know of. Two prominent ancient philosophers and their schools are especially notable for their connections to modern teaching methods: Aristotle and Epicurus.

Before we start, there is a small caveat: it is important to note that the teaching methods from ancient Greece were used mostly for adult learning, qualifying it as ‘andragogy’ (adult teaching methods) rather than ‘pedagogy’ (child teaching methods). While keeping this in mind, most of these methods are just as effective and suitable for young students, with some possible adjustments and adaptations.

We begin with Aristotle. A student of Plato, Aristotle imbibed the common practice of philosophising while walking. Socrates, Plato’s own teacher, was often observed to philosophise while in motion – the historian Plutarch reports that he ‘did philosophy without setting up benches or seating himself on a throne’. Comic playwrights mocked Plato’s own habit of walking while philosophising, as when one character in a popular comedy complained: ‘I’m at my wit’s end, walking up and down like Plato, and I’ve worked out no wise plan, I’ve only tired out my legs!’

But walking is most closely associated with Aristotle. His school, the Lyceum, was founded around 335 BCE, a converted gymnasium. The philosophers who gathered there came to be known as Peripatetics – the word means ‘walking about’ in ancient Greek – perhaps because of their ambulatory habits, or because of the colonnade that wreathed the Lyceum, called a peripatos. Aristotle seems to have held lectures, often mobile, for the general public.

Physical movement can help students better understand concepts and improve their reasoning skills

The philosophical idea behind the practice of ‘walking about’ in the peripatetic school was that learning takes place while being in motion and interacting with one’s surroundings (Plutarch also says that Socrates taught philosophy ‘while drinking’ and ‘while on military campaign’: pedagogies that haven’t found much favour today). Direct interactions with the natural environment around us can spark our sense of wonder and curiosity about the world, which are critical for learning and for philosophical investigations. This peripatetic approach to teaching hints at one of the most effective learning strategies we know today: ‘embodied learning’.

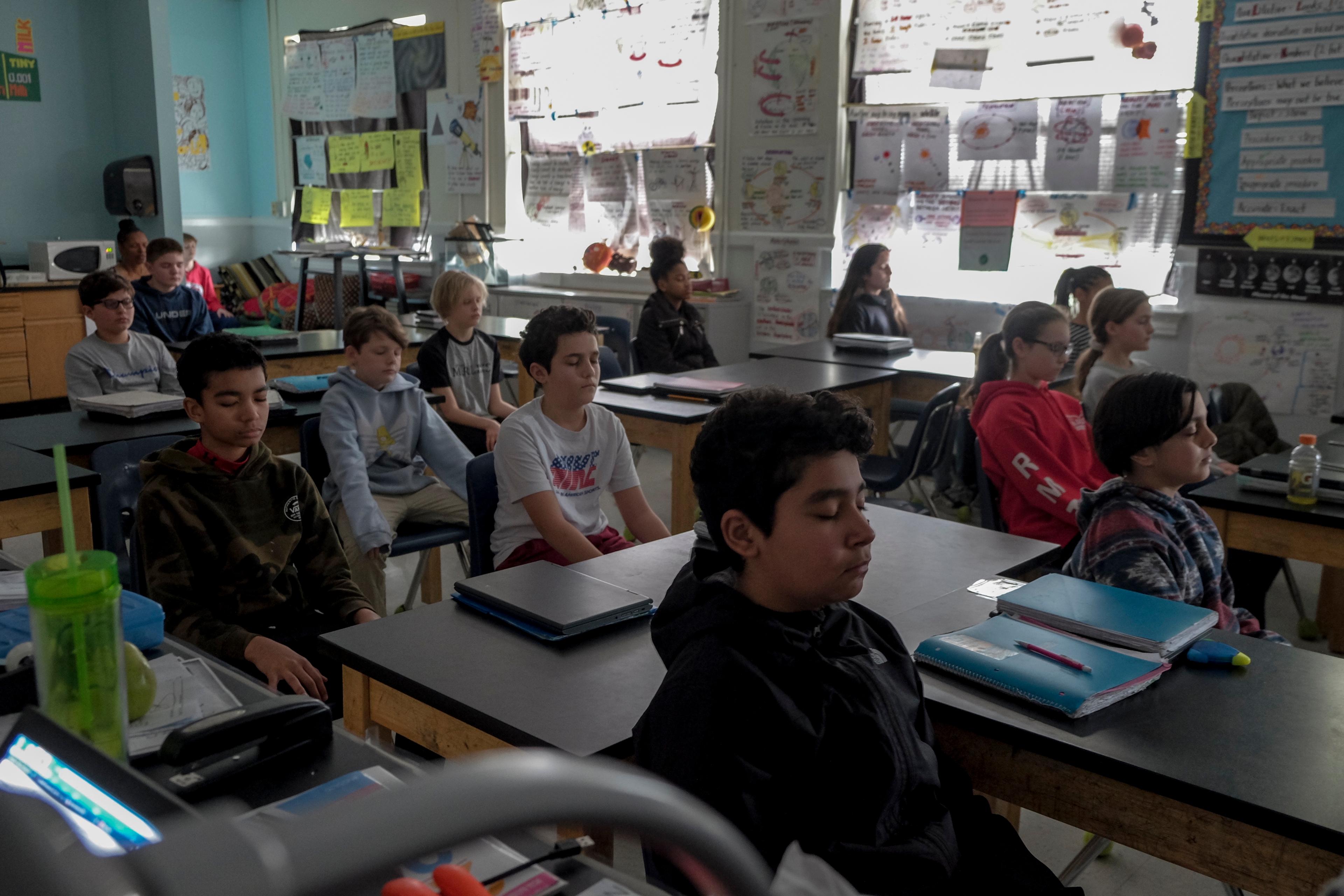

The main concept of embodied learning (also known as ‘embodied cognition’) is that learning does not take place exclusively inside our mind, but requires continuous sensory stimulations from different body parts, alongside interactions with the environment around us and the people in it. This idea is connected to the extended mind theory, proposed by Andy Clark and David Chalmers in their 1998 paper and described in Annie Murphy Paul’s book The Extended Mind: The Power of Thinking Outside the Brain (2021). In education, this approach relates to the theory of ‘situated learning’, in which students are encouraged to be active, collaborate with each other, and interact with their environment during the learning process. This holistic approach has been proven to be more effective than passive learning done by static transfer of knowledge from the teacher to the students.

When engaging students in embodied learning, it is important to have them move, play and use their body and senses as much as possible. Studies show that physical movement can help students to better understand concepts and to improve their reasoning skills in many school subjects such as a second language, mathematics, and the sciences. Embodied learning also requires meaningful interactions between people, a method known as ‘collaborative learning’. This pedagogy aims to engage students in active collaborations between themselves and with other people, such as group enquiry projects, shared discussions or cooperative problem-solving. Project-based learning (PBL), which is grounded in concepts from situated and collaborative learning, is one of the most effective educational pedagogies. PBL was found to support students’ content learning, increase their interest in learning, and advance their skills relevant to the 21st century. In PBL, learning starts by engaging students with a relevant real-world phenomenon and driving question that sparks their curiosity and creates the desire to ‘figure it out’ – just like the idea that Aristotle practised in his peripatetic school by walking around and engaging with the natural environment.

To put all this in context, here is an example of a PBL activity for high-school chemistry students that our research team developed and implemented in several schools. It begins by introducing the students to a phenomenon and a driving question that will guide the learning: they perform a small experiment, such as an observation of what happens when you drip a few drops of different transparent liquids on the hands. They observe that water drops evaporate much slower than drops of alcohol or acetone, and that the water drops form a much rounder shape than the other drops (you can try it at home). This realisation creates the desire to explore and understand the reason why this phenomenon occurs, encouraging students to engage in collaborative investigations to learn the chemistry of intermolecular forces.

In another study, our research team developed a PBL unit for middle-school science students focusing on ant communication. We started by having the students observe an ant trail in a video recording or outside in nature. They could observe how ants collect food and bring it to their nest from far-away locations (in ant scale, at least). To understand this phenomenon and to answer the driving question ‘How do ants communicate to create a food trail?’, students engage in several investigations of ants in nature and learn how ants communicate by chemical pheromone secretion.

The physical location and structure of the Garden were crucial to Epicurus’ hedonistic philosophy

PBL also requires the students to produce and present tangible artefacts, such as a model, a poster or a device that demonstrates their knowledge and abilities following the learning process. In our research, we’ve studied the effect of shifting from traditional classroom teaching to PBL, finding that, while this shift poses some challenges for both teachers and students, it provides students with relevant learning experiences, increases their engagement in the lessons, and advances their academic achievements.

We turn now to another philosopher of ancient Greece, who thrived a generation after Aristotle: Epicurus. In around 307 BCE, he founded a school outside Athens called the Garden. The physical location and structure of the Garden were crucial to Epicurus’ hedonistic philosophy. Here Epicurus’ students lived, studied and conversed together, and they aimed to be self-sufficient by gardening and growing their own food, relishing the simple pleasures of their Garden (scandalously for the times, his students included women and at least one slave). Epicurus’ approach to teaching – taking place outside, within the walls of the Garden, and in deep interaction with nature and the environment – alludes to another important method related to embodied learning, called ‘place-based learning’.

This method encourages outdoor learning that allows students to explore their immediate environment, whether in city streets, in nature parks or in community spaces. It enables them to develop contextual knowledge and skills, and fosters a sense of belonging. These outdoor experiences can sometimes be stressful for the students, as they may venture into unfamiliar environments outside their school and experience learning that breaks the typical classroom teaching. However, if done properly, these experiences can boost their sense of wonder and curiosity about the world around them while advancing their learning achievements.

In another study, we’ve investigated students’ learning while implementing a place-based and project-based curricular unit focused on investigating a watershed in the school area. Students performed experiments and surveys to determine the water quality, and assessed human-related water-polluting factors in the environment. While learning about the water quality in the local watershed, they developed, tested and revised computational models that explain how the different factors in the environment contribute to the water quality. These modelling activities also provided students with an opportunity to share, discuss and give feedback to their peers, supporting their collaborative learning. Although most PBL studies do not compare the learning outcomes of PBL with traditional classroom teaching, it was found that engaging student in PBL can advance their higher-order thinking, social collaborative abilities, motivation and interest in learning, content understanding and problem-solving skills.

We are still far from realising this ideal image of teaching and learning, as most educational systems are designed in the traditional teacher-centred, content memorisation-oriented, academic achievement-focused, one-size-fits-all approach. However, more and more innovative pedagogies such as embodied, project-based, place-based and collaborative learning, with their historical roots in ancient Greece (and other cultures), are making their way into modern schools.

In addition, we should also consider how the advanced technological tools that are now available to us can effectively support these innovative pedagogies. Also, we should acknowledge that there is no one perfect pedagogy that is suitable to all teachers, all students and all schools in every situation. An expert teacher knows how to engage her students in different teaching methods, depending on the context in which the learning takes place. And finally, we should always be aware that at the core of any teaching and learning experience stand the students – with their curiosity, inquisitive questions and desire to engage with the world around them.

This Idea was made possible through the support of a grant to Aeon+Psyche from the John Templeton Foundation. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Foundation. Funders to Aeon+Psyche are not involved in editorial decision-making.