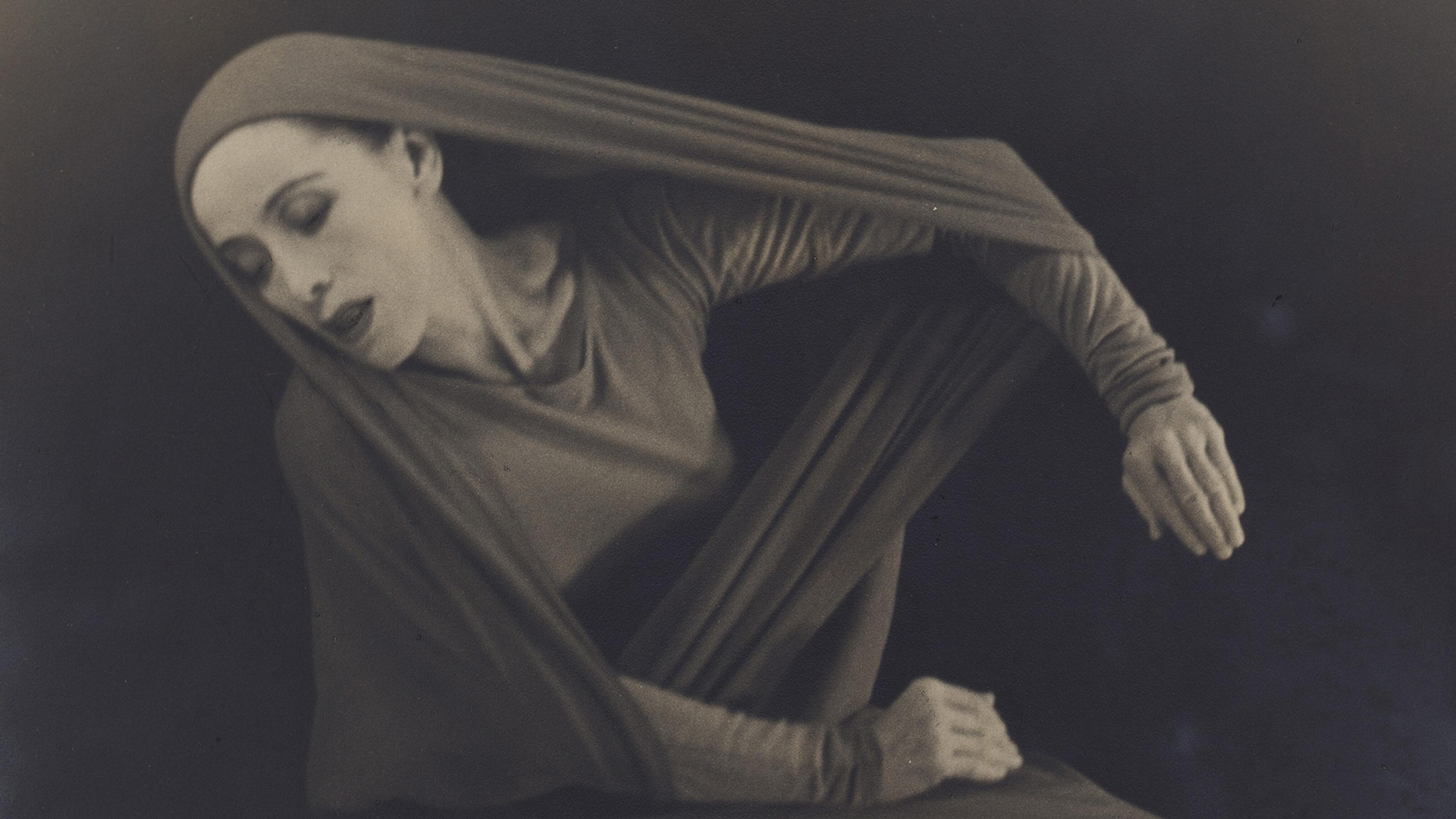

In the darkness of the Maxine Elliott theatre in New York, on 8 January 1930, a solitary figure is draped over a bench. Her body’s contours seem to be at one with a large swathe of purple fabric. Every beguiling motion she makes, her torso bending, rising and twisting, is different to the one preceding it. Throughout much of Lamentation, Martha Graham remains entirely seated. Within the constrained space she has created, and the constraining jersey tube she moves within, she explores her isolation. Lamentation was the radical work that brought soaring Modernism into the world of American dance and made Graham a household name.

Ninety years since it premiered, Lamentation continues to occupy a central place in the Martha Graham canon, and within modern art beyond it. Graham’s lamenting torso has spilled into references in the new version of Walt Disney’s Beauty and the Beast, via choreographic homage, as well as in works by Andy Warhol, who made screenprints of Graham’s solo in 1986, and Madonna, photographed by Peter Lindbergh in 1994, channelling Graham in that jersey tube.

The Martha Graham Dance Company, meanwhile, has been generously sharing resources online, from dance classes and workshops to a twice-weekly screening of archival materials from the company’s rich history under the title ‘Martha Matinees’. In March and June 2020, during the global lockdowns occasioned by the COVID-19 pandemic, the matinee offered several versions of Lamentation, as well as a new-found film of Graham dancing the piece in 1943. The theme of the universality of grief, as well as the tension of confinement and expansion that echo throughout Graham’s performance, acquire a double meaning by being viewed at this time, when contemporary spectators, shielding from the virus, are isolated inside their own grief.

Janet Eilber, the artistic director of the Graham Company, says that Graham created Lamentation at the start of her dance revolution, before she began layering in references to the social and political issues of the day:

She was experimenting – searching for a way to embody the essential – and nothing else … In 1930, she struggled to isolate one basic universal thing and to represent it in movement. She succeeded with Lamentation [which] is stripped down to the essence of human feeling – so much so that we do not even see the dancer’s arms and legs. Martha has invented and chosen a collection of shapes and movements that are reliant on self-containment and isolation – and that speak to self-containment and isolation.

In Lamentation, I see two ideas that resonate with my own perception of dance in times of isolation: the richness of possibility of movement within one moving body, as well as the connections between a singular moving body in isolation and the world it inhabits, sharing joy as well as profound sorrow and grief.

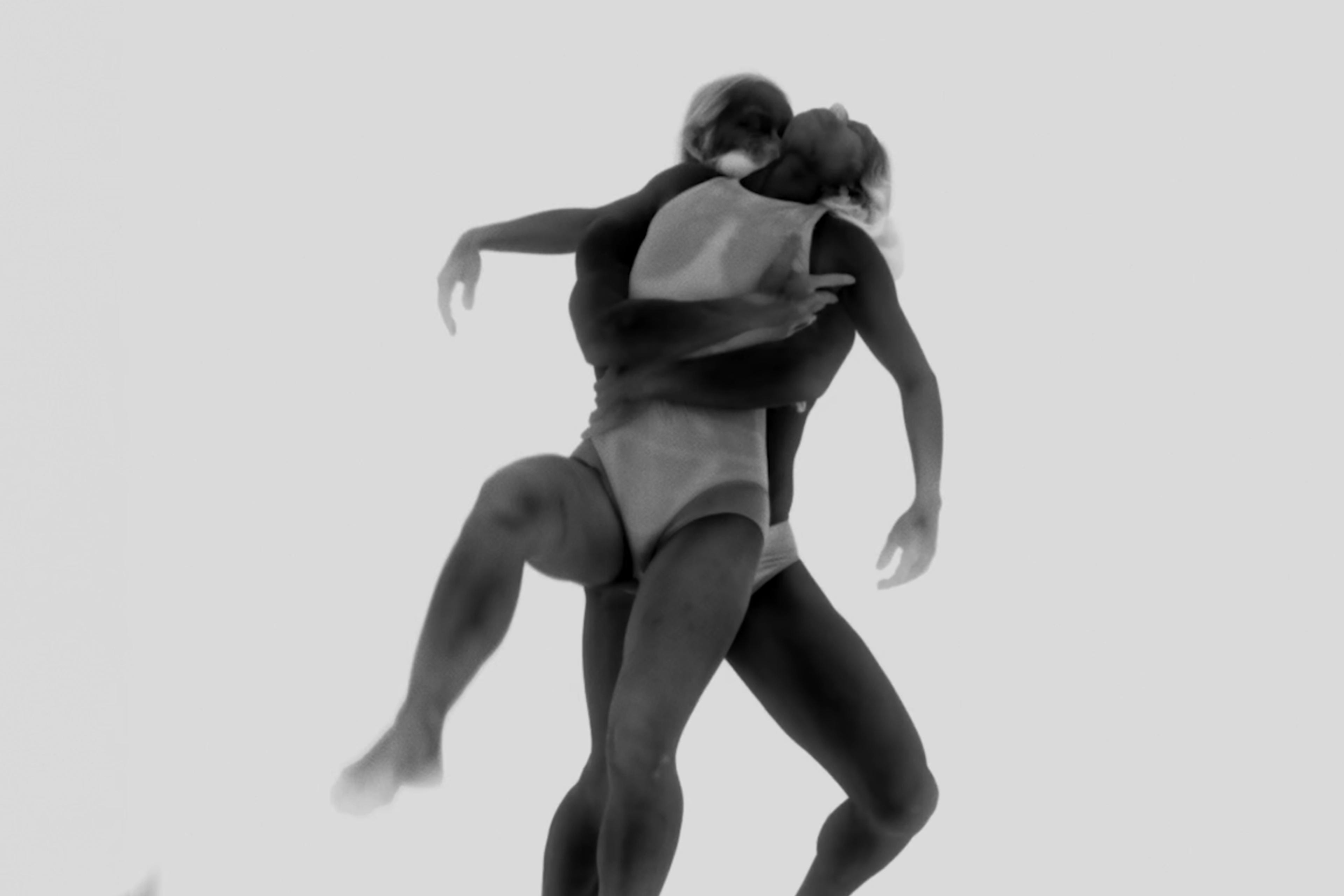

The Martha Matinees are timely. Since the worldwide lockdowns began, there’s been an explosion of movement and dance in confined spaces. Online dance classes have seen people learning to tango in their living room and tap-dance in their kitchens, and social distancing rules have led people to join impromptu dance parties from balconies and front drives. TikTok, a social media platform that’s rapidly become a signature of our times, has allowed teenagers to post choreographed sequences and join other communities performing the same moves. Dancing in confined spaces, both in Graham’s Lamentation and in online dance during lockdown, stripped dance to its most essential components, allowing people to explore the richness of gesture, just as Graham did in her revolutionary moment. Under harsh conditions of isolation, this stripping back of dance to nothing but bodies moving together is, in itself, a radical re-articulation of the connection between one moving body and others.

Whenever we reflect on the world within the confined space of our minds, we effectively engage in a silent dialogue. We learn to hold within our inner lives at least two voices in conversation with each other. Just as thinking occurs inside the enclosed space of the head when we talk to ourselves in language, movement is also a result of embodied dialogue within that enclosed first space we inhabit: our body. Dance, a nonverbal way of thinking, works within an embodied dialogue. Our bodies are moulded by incorporating gestures and movements from others, just as our verbal thinking responds to words and sentences that affect our inner dialogue. When we sense others moving in different ways, we acknowledge our own possibilities of movement beyond what we thought possible.

In The Life of the Mind, her last (and incomplete) book, published posthumously in 1977-78, the political theorist Hannah Arendt examined the process of thinking through dialogue, and especially its implications for the way we inhabit our shared spaces. Venturing into philosophy (which also connects the life of the mind to our life with others), she discusses the internal dialogue she terms ‘two-in-one’ – that inner communication we all know deeply within ourselves, and that shapes how we perceive our political and moral worlds. Arendt’s investigation of thinking led her to reflect on how this dialogue affects our relationship to others, since our ability to bounce back from the world into our two-in-one requires that we are part of communities, engaging in discourse with others. Arendt notes that: ‘Loneliness comes about when I am alone without being able to split up into the two-in-one, without being able to keep myself company …’ Because we are able to internalise dialogues with others in our two-in-one state, we can keep ourselves company. Even when isolated, when we are able to speak to ourselves, we are not alone.

Dance works within conversations that unravel through our embodied two-in-oneness. When we sense others moving in different ways, we can acknowledge our own possibilities of movement. Likewise, when we dig deep into the embodied self. We learn how to keep ourselves company through movement, generating an internal dancing dialogue that allows us to explore and experience our embodied two-in-one.

The lockdown has, paradoxically, opened up new ways to experience dance, for dancers and spectators alike. As a lover of dance who used to struggle to find time to make it to a physical studio, I’ve since found myself indulging in the high standard and variety of classes and activities online. At the same time, experiencing different movement techniques in my sitting room changed the way that I understood dance, the way I felt within my own body, and how I saw the space in which I was dancing in isolation. As I executed the fundamental action of turning my spine towards the back wall in different movement classes, each turn felt different, and changed the way I felt in my ad-hoc studio. My little sitting room suddenly provided me with seemingly endless possibilities of movement, and my own body felt like clay that I could mould in numerous positions, textures, rhythms and flows. Moving with many people from around the world, some whom I knew before we had gone into lockdown and some new comrades in dance, meant that, although I’d been self-isolating while dancing, I was never lonely.

The pandemic has brought a new urgency to our sense of mortality and to the way we inhabit our bodies. Suddenly, issues that preoccupied our psyches are pushed away in favour of contemplating life and death. Watching Lamentation in self-isolation invokes not only the movement of a body within a confined space but the connectivity of all of us human beings facing the inevitably of an end. Grief and mourning are the dominion of too many. The fear for loved ones, and the heartbreak of losing them, unites humanity and echoes urgently now. At the same time, perhaps as a function of our two-in-one awareness, we can also connect profoundly with each other through our ability to find joy, solace and a path for healing by dancing together.

And so, the perched body, expanding from 1930 into our own times, provokes our embodied dialogues, sees us moving in confined spaces, but always able to expand beyond their physical boundaries via the horizons of our embodied imaginations. For myself, as well as for many others, dancing in self-isolation has created a vital community that has sustained us. Together with people I’m not likely to ever meet beyond my computer screen, I’ve marked successes, worked through grief, ended days both productive and frustrating. There were terrible days too, but we danced through them all. There was a special moment when I took part in a dance improvisation alongside nearly 800 people from around the world, as well as a unique intimacy that I formed with three people who diligently turn up to a rigorous online dance class. Lockdown has posed immense challenges for us, as moving, social and embodied beings. Yet by delving deep into the embodied two-in-one, we’ve been able to explore the richness of our moving bodies, and learn anew that we can move alone yet not be lonely.

In memory of my father, Harold Llewellyn Mills (1925-2020), who taught me how to love dance.