You meet with a friend to take a walk. Together you stroll through the park, coordinating your movements and reciprocally engaging and communicating with one another. According to the British philosopher Margaret Gilbert, this is a paradigmatic case of experiencing oneself as part of a ‘we’: two people communicatively connected and joint in their commitment to take a walk and catch up.

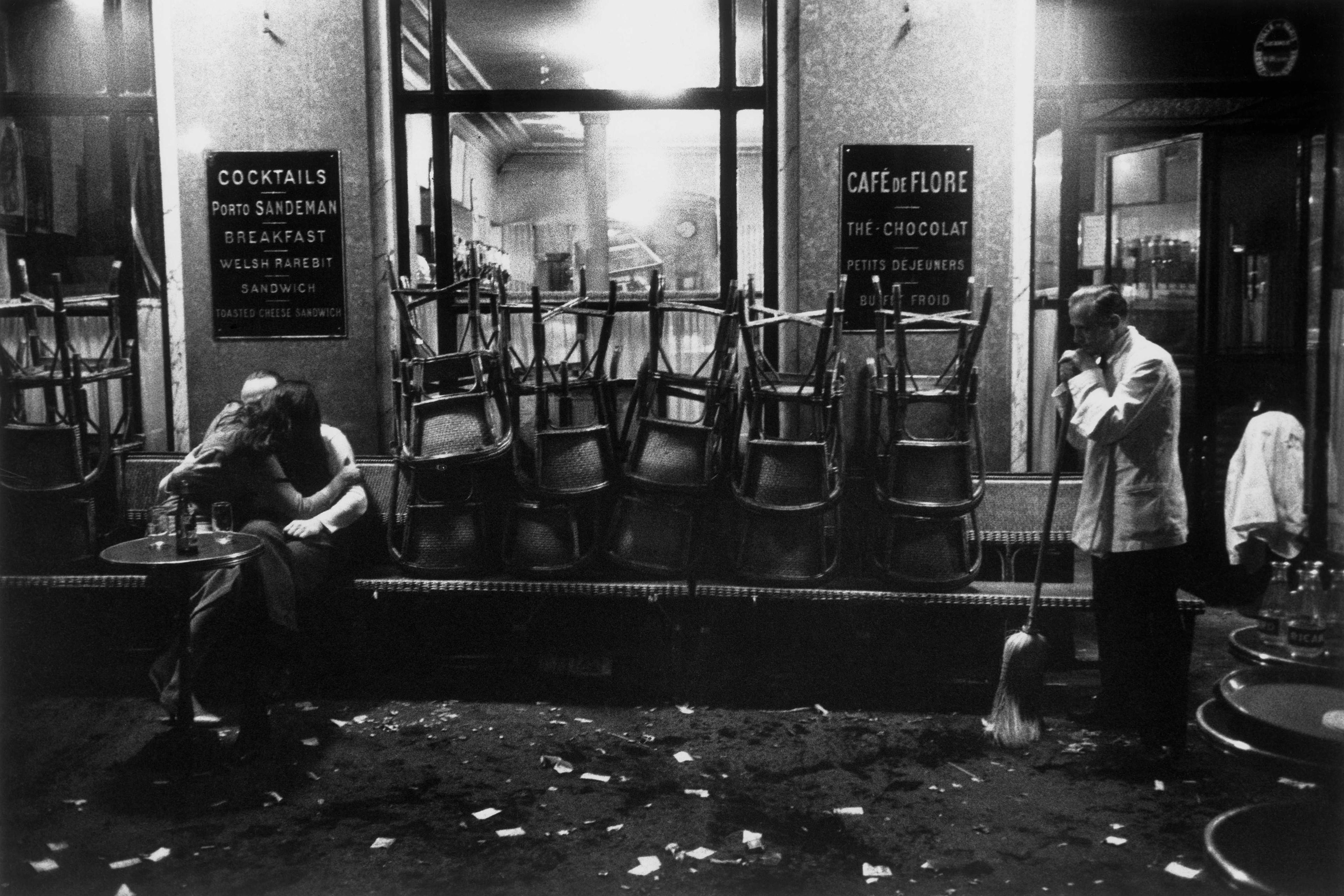

But what happens when suddenly you become aware of someone staring at you, perhaps listening in on your conversation? In this moment, you may be pulled out of the intimately closed-off dyad as you are abruptly made aware that the two of you have become the object of someone else’s experience, either visually or auditorily. You now experience yourselves not as a private ‘we’ but as a ‘them’ in the eyes of the other.

What this brief anecdote illuminates is the phenomenological distinction between a ‘we’ and an ‘us’. First, we took a walk together and were unified from within, by our sharing in commitments, goals, communication and emotions. Then, we experienced ourselves being unified from the outside as we noticed someone looking at and listening to us.

This may sound like a mere grammatical distinction, but in this short article I want to draw on existential and social phenomenology to show that the distinction between a ‘we’ and an ‘us’ in fact points to an important experiential shift – a shift that reveals something deeper about how we live in a social world saturated with power relations, group markers, and social identities.

Phenomenology is a school of philosophical thought established by Edmund Husserl at the turn of the 20th century. This philosophical tradition enquires extensively into first-person experiences and thus a range of complex issues surrounding consciousness, selfhood, embodiment, perception, affectivity, temporality, and intersubjectivity. While phenomenology began with analyses into the first-person singular – how I experience the world through my embodied subjectivity – a great deal of phenomenologial work has since been dedicated to enquiries into the first-person plural.

When nationalism was on the rise in Europe in the early 20th century, phenomenologists began exploring forms of experience at communal and societal levels. This yielded comprehensive investigations into collective and shared experiences, affective sharing, social participation and group identity. After the Second World War, phenomenologists then engaged rigorously with questions of group-based oppression, marginalisation, exclusion, and how hierarchical distinctions become sedimented into the fabric of our social world.

One shortcoming is that their analyses of the ‘we’ and ‘we-experiences’ are abstract and idealising

A central tenet of this research in social phenomenology pertains to the conditions of going from a first-person singular to a first-person plural perspective. In other words, the transition from an ‘I’ to a ‘we’; from an experience being singularly mine to collectively ours. This transition has also taken centre stage in wider philosophical investigations within social ontology, the field of philosophy that investigates how things come to be through social interaction.

One shortcoming of many of these mainstream philosophical accounts – both from the phenomenological tradition and from contemporary social ontology – is that their analyses of the ‘we’ and ‘we-experiences’ are abstract and idealising. Abstract in the sense that the plural subject is shorn of any sociohistorical situation, and idealising because the ‘we’ is characterised by cooperation, consensus, equality and reciprocity.

But what about those moments in which we situate a collective of people in the world – a world not only inhabited by other people, but one that is saturated with power relations, conflict and historically instituted hierarchical distinctions? To do this, I turn to existential phenomenology, a branch of phenomenology that foregrounds how historically contingent institutions affect lifeworld-specific variations of basic structures of human existence. One thinker who was interested in adopting such an existential-phenomenological social ontology was Jean-Paul Sartre.

In Being and Nothingness (1943), Sartre elaborates on the existential and philosophical importance of what he calls ‘the Look’. Unlike earlier accounts that emphasised how the first-person plural emerges out of the relation between I and you, Sartre is interested in how they relates to me as an object. ‘The Look’ groups us together from the outside into an objectified and homogenous ‘them’, pulling us out of the self-contained and self-created ‘we’ that was unified from within.

In extending the existential and phenomenological importance of ‘the Look’ to collective (rather than individual) experience, Sartre draws a distinction between the ‘we-subject’ (le nous-sujet) and the ‘we-object’ (le nous-objet). Since nous in French is used for the first-person plural, in English we could translate Sartre (as his American translator Hazel Barnes did) as drawing a distinction between the ‘we’ and the ‘us’. Sartre himself was wary of deriving theoretical insights from mere grammatical categories, especially when many languages do not even use or differentiate between a first-person plural pronoun. But, as the philosopher Sarah Pawlett-Jackson argues in The Phenomenology of the Second-Person Plural (2025), pronouns came into use precisely in order to capture a particular form of lived experience, a particular phenomenological standpoint.

In many languages, the first-person plural pronoun can take on both a subjective (or, nominative) and objective (or, accusative) form. In English, ‘we’ is used when referring to the plurality as the subject (of an action, belief, judgment, emotion, perception, etc). We saw a movie at the cinema. We need to move the table. We are indignant. However, when that plurality becomes the object, it is referred to instead with the pronoun ‘us’. The cinema didn’t let us in. That table is too heavy for us. They were indignant towards us.

In other words, whereas a we-experience is a plurality of subjects who are jointly conscious of an object, an us-experience involves a double consciousness. Not only are we conscious of each other and a shared object of experience, but also of us as an object that stands in relation to them, the external Third. It is Sartre’s introduction of ‘the Third’ onto the scene that resists the collapsing of the first-person plural into the ‘we’, instead introducing the ‘us’ as something phenomenologically distinct.

Double-consciousness refers to ‘measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity’

So, what does it mean to have a ‘we-experience’ in comparison to an ‘us-experience’? Anglophonic philosophical discussions around the first-person plural have almost entirely focused on the ‘we’. By taking the subjective form of the first-person plural as the modus operandi of their investigations, phenomenologists have been predominantly concerned with how we do things together in reciprocal and communicative face-to-face interaction. In order to experience the world from a ‘we-perspective’, certain basic criteria need to be met. First of all, there must be a plurality of subjects who are undergoing the experience. If I am the only person enjoying the sunset, my enjoyment is felt by me as an individual subject, rather than by we as a plural subject. Secondly, the subjects must be unified in some sense. If a stranger sitting near me is enjoying the same sunset, it would be presumptuous to say that we experienced it together unless our enjoyment has been communicated to one another. We haven’t created the necessary unity.

An experience of oneself as a member of an ‘us’ rather than a ‘we’ can be understood to have a distinct phenomenology in two important respects. First, whereas a we-experience can take place between a dyad, an us-experience is necessarily triadic in its structure. A felt sense of ‘us-ness’ can arise only in relation to an external Third element. It is important not to delimit the Third to face-to-face encounters; the Third can be represented through various forms of media, from political posters to radio announcements to graffiti, and thus the Third is encountered with varying degrees of mediation. One can be made reflectively self-aware through ‘the Look’ of the Third by hearing a rustling of branches, the sound of footsteps, or a CCTV camera turning to face your direction.

This foregrounding of being-seen through the Other is reminiscent of the notion of ‘double-consciousness’, first introduced by W E B Du Bois in his essay ‘Strivings of the Negro People’ (1897). For Du Bois, double-consciousness refers to ‘this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity’ – a commonplace experience for Black people living in a white supremacist society. This understanding of double-consciousness influenced early work in existential phenomenology, especially that of Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, through the work of their friend and collaborator, the African American author Richard Wright, for whom Du Bois was an important source of inspiration.

With us-experiences, one can speak of a plural or collective double-consciousness. The members of the ‘we’ are no longer singularly conscious of a shared object of experience, but are doubly conscious of themselves as an object of experience. In this sense, an us-experience arises because of a collective relation to an external Third.

Disentangling the ‘we’ from the ‘us’ is helpful in going beyond the idealising and abstract philosophical discussions in social ontology because it foregrounds the manifold ways in which we experience ourselves being categorised, grouped together, and stereotyped according to certain markers. Plural markings are often the result of sociohistorically instituted identity categories, groupings and hierarchical oppositions. For this reason, first-person plural experiences in terms of race, gender, sexuality, ethnicity, disability, age and so on often take place in the register of the ‘us’ rather than the ‘we’. This is because these social-identity categories are instituted and policed according to visible markers. While they can be appropriated for emancipatory struggle – and in such cases we can speak of a we-experience at the level of race or gender, for example – they are more often externally imposed in stereotypical, prejudicial and derogatory processes of othering.

So, us-experiences can be less harmonious, consensual and self-endorsed than we-experiences since their constitution hinges on these external impositions. Of course, being part of a ‘we’ can also be negatively valenced, such as the ‘we’ that emerges out of an argument or fight, but to experience oneself as part of an ‘us’ bears no necessary link to feeling a positive sense of commonality with the other members.

Yet the ‘us’ is not simply the dark and depressing side of the ‘we’. As Sartre went on to show in his later work of existentialist Marxism, it is often from the alienated, marked and stereotyped ‘us’ that collective struggle, political action, and a coordinated and resistant ‘we’ emerges. In becoming conscious of one’s position in the social world, you, and others like you, can prompt a response of resistance to dismantle and overcome the social constraints that one collectively faces with others. An emancipatory transition from an ‘us’ to a ‘we’ takes place when the external Third loses salience in lieu of an internal unification and organisation that comes about to reclaim agency over ‘them’. Existential phenomenology, far from being an esoteric philosophical discipline, has crucial political importance in helping people collectively see themselves as agents of change.