You can accept the idea that everything passes. You can read the Stoic philosophers, who teach us to accept death as inevitable; you can follow their advice to practise memento mori (remembering death as a way of appreciating life); you can meditate on impermanence. I do these things regularly. They prepare you to some degree. But the terrible beauty of transience is much greater than we are. In our best moments, especially in the presence of sublime music, art and nature, we grasp the tragic majesty of it. The rest of the time, we simply have to live it.

The question is: how? How are we supposed to live such an unthinkable thing?

My brother was 62 when he died. He’d met his love, Paula, seven years earlier. They were devoted to each other from the start, married a few months before the COVID-19 pandemic struck. It was his first marriage. At their wedding, he observed that some of the toasts were on the theme of ‘Better late than never,’ but the real message was ‘Worth the wait.’

In the days after his death, his hospital colleagues told me stories about him. That he was known to bring a portable ultrasound unit to a patient’s room in the middle of the night, to double-check a difficult diagnosis. That time was of no importance to him: ‘The patient was his only concern.’ That he’d recently won the award for Outstanding Lecturer, and another for Teacher of the Year, his department’s highest honour. He was a modest person; I wasn’t surprised that he’d never mentioned these achievements. But I would have liked to say congratulations.

My brother was 11 years my elder. He taught me how to ride a bike; he invented a game in which, if I broke this absurd rule or that one, I’d have to go to ‘proper school’ – I can still see him at the phone in the family kitchen, pretending to talk to the teachers who ran the imaginary school. In the days after his death, all these memories crowded my mind at five in the morning. It all happened so many years ago. What once was will never be again.

But what if things could be different? What if you never had to accept that everything passes?

The first immortalist I met was Keith Comito, a computer programmer, mathematician, technology pioneer – and the president of the Lifespan Extension Advocacy Foundation in New York. He has a narrow, friendly face and crinkly brown eyes; on the day we get together, at his favourite coffee shop in Greenwich Village, he’s wearing a T-shirt emblazoned with a periodic table of Marvel characters. He awaits me with green tea in hand: he gave up coffee in college, he explains, back when he thought it was bad for you. Staying up until 3am to complete his many projects is also bad for longevity, he acknowledges with a dimpled grin, but there’s too much he wants to accomplish while he’s still alive: especially longevity, which, for him, is the holy grail.

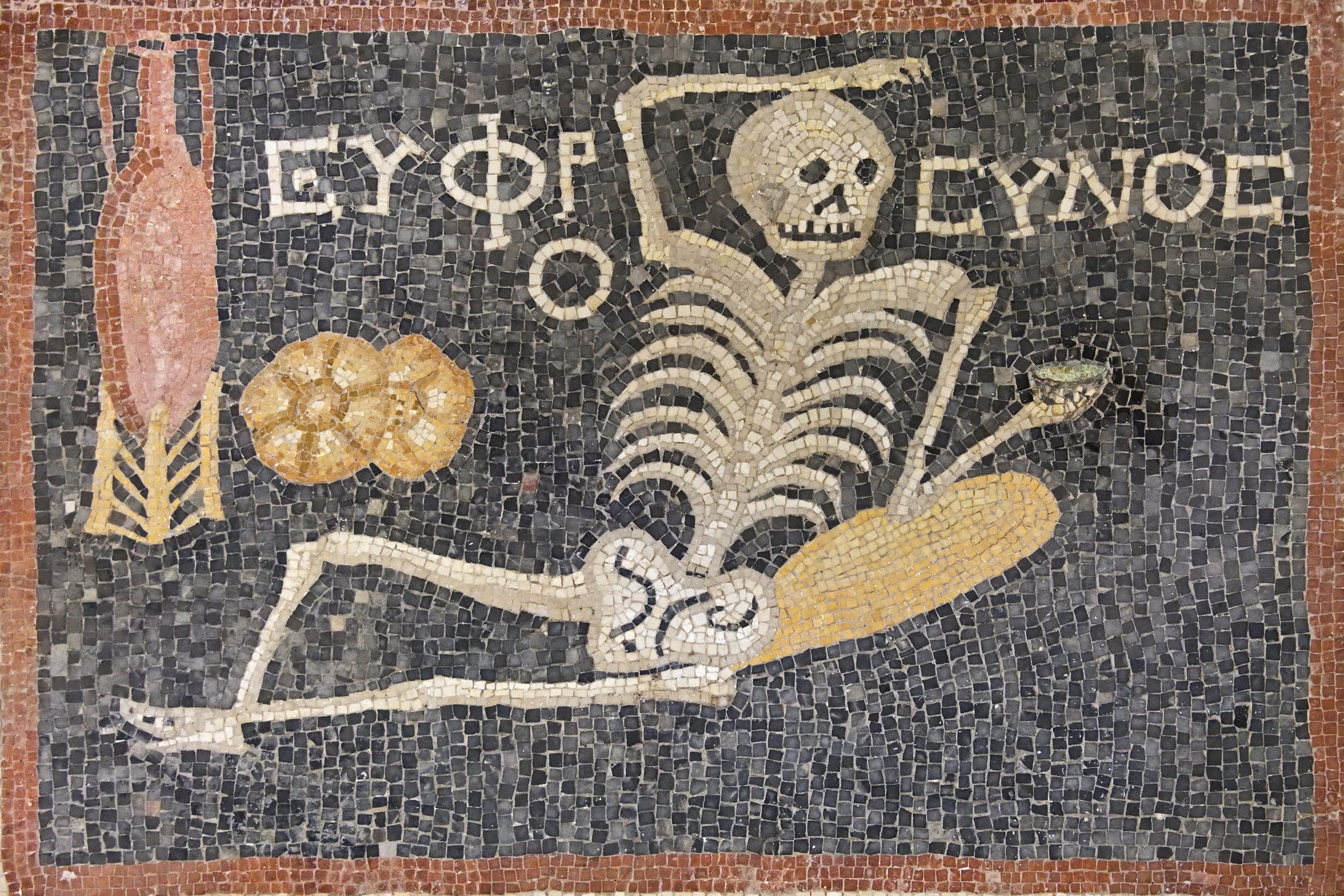

Comito acts in conscious homage to the Epic of Gilgamesh, the world’s first great work of literature, about a king longing for immortality. Comito bounces in his seat, literally becomes airborne, as he recounts the ancient tale: the seeking, questing king who found the flower of immortality and tried to bring it back to his people, but when he stopped to rest, a snake ate the flower. Immortality is the real goal of all heroes’ journeys, Comito declares; Star Wars and the Odyssey are just sublimated versions of the age-old desire to live forever. He sees himself as such a protagonist, but without the sublimation part.

‘How exciting is it to be alive right now that you potentially get to finish the first hero’s journey,’ Comito says to me. ‘How exciting that we get to bring the flower back! People are looking for meaning in their lives? This is the first meaning that ever was – since the first stories were carved in stone!’ He gesticulates expansively, his hand periodically colliding with my laptop, for which each time he pauses to apologise genuinely. In high school, I think, he would have been nerdy but well liked for his irrepressible enthusiasm. ‘You get to bring the flower back!’

But when you take a closer look at Gilgamesh and the other literature of immortality – from Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726) to the legend of the ghost ship the Flying Dutchman, the topic has always captured authors’ imaginations – the storytellers are mostly warning us. That it’s not only impossible to live forever (the snake will eat the flower) but also unwise. That we’d take up too much space. That, after a few hundred years, we’d get bored; life would lose its meaning.

Comito is not the only expert who is deadly serious about extending our lives. In August 2017, at the Town and Country hotel and convention centre in San Diego, I met others who were speaking at the second annual RAADfest conference – ‘the Woodstock of radical life extension’. RAAD stands for the Revolution Against Ageing and Death. The adherents of this cause go by various names: anti-death activists, radical life-extension advocates, transhumanists, super-longevity enthusiasts. I call them ‘immortalists’. Among their ranks are the cryobiologist and biogerontologist Greg Fahy, who uses human growth hormone to regrow thymus, a key ingredient of our immune systems; the geneticist Sukhdeep Singh Dhadwar at Harvard Medical School, who’s trying to bring the woolly mammoth back from extinction while also searching for the genes that cause Alzheimer’s; and Michael West, a renowned polymath who was one of the first scientists to isolate human embryonic stem cells, and whose biotech company aims to cure age-related degenerative diseases. Since 2017, the life-extending work of the immortalists has flourished.

They want a life that’s free not only of death, but also of illness and decrepitude. They want to heal us all.

The most common objection to the immortalist project is that it’s delusional – no matter how advanced our technology gets, the snake will always eat Gilgamesh’s flower.

But the deeper concern is that humans aren’t meant to be gods. If we did live forever, some wonder, would we still be human? If our capacity for love and bonding emerges from our impulse to care for tearful infants – as shown by the research of Dacher Keltner, professor of psychology at Berkeley – what happens when we lose our vulnerability? Could we still love and be loved? If, as Plato said, we can’t grasp reality without contemplating death, what would it mean to bypass it altogether? And then there are the practical concerns. If we defeat death before we find other habitable planets, will there be room for everyone? Will we usher in a new era of scarcity and conflict?

Some immortalists have ready responses to these quibbles. Not only are they going to cure death; they’ll remove loss from the human condition, and elevate love in its place. If we can solve mortality, they reason, then we can figure out how to cure depression, end poverty, stop wars. ‘I think it is absolutely true,’ one scientist at RAADfest told me, ‘that when we solve one of the core problems facing humanity [ie, death], we’ll somehow empower ourselves to have more of a shot at the other ones. Especially because this problem of mortality has ground us down since the dawn of civilisation. If we could do this, we could do anything.’

Part of this utopian vision – at least the part that has to do with world peace – derives from a field in social psychology called terror management theory. According to this theory, the fear of death encourages tribalism, by making us want to affiliate with a group identity that would seem to outlive us. Various studies by the social psychologist Tom Pyszczynski and others have shown that, when we feel mortally threatened, we become jingoistic, hostile to outsiders, biased against out-groups. In one such experiment, subjects who were reminded of death were more likely than the control group to give their political opponents mouth-burning quantities of hot sauce. In another study, politically conservative students instructed to think about what would happen to their bodies when they died were more likely than a control group to advocate extreme military attacks on threatening foreign nations. So if immortality frees us from our fear of death, goes the thinking, we’ll grow more harmonious, less nationalistic, and more open to outsiders.

The founders of People Unlimited, the Arizona-based producers and sponsors of RAADfest, adopt this view explicitly. As their website explains:

There is a big-picture message we feel is vital to deliver – that immortality, rather than being a dehumanising element as Hollywood vampire stories suggest, in fact brings out the best in our humanity. It doesn’t just end death, it ends the separation between people; by neutralising the inherent fear of death, immortality empowers us to open our hearts to people like never before. The toxicity of contemporary life is a serious threat to our health, and perhaps the greatest toxicity is that which comes from people.

This deathless passion creates a whole new level of togetherness in which people are lifted by people, rather than brought down.

It’s a nice idea, but solving toxicity and conflict is unlikely to be this simple. Indeed, our true challenge may not be death at all (or not only death), but rather the sorrows and longings of being alive. We think we long for eternal life, but maybe what we’re really longing for is perfect and unconditional love; a world in which lions actually do lay down with lambs; a world free of famines and floods, concentration camps and Gulag archipelagos; a world in which we grow up to love others in the same helplessly exuberant way as we once loved our parents; a world in which we’re forever adored like a precious baby; a world built on an entirely different logic from our own, one in which life needn’t eat life in order to survive. Even if our limbs were metallic and unbreakable, and our souls uploaded to a hard drive in the sky, even if we colonised a galaxy of hospitable planets as glorious as Earth, even then we would face disappointment and heartbreak, strife and separation. And these are conditions for which a deathless existence has no remedy.

Maybe this is why the prize, in Buddhism and Hinduism, is not immortality, but freedom from rebirth. Maybe this is why, in Christianity, the dream is not to cure death but to enter heaven. We’re longing, as mystics might say, to reunite with the source of love itself. We’re yearning for the perfect and beautiful world, for ‘somewhere over the rainbow’, for C S Lewis’s ‘place where all the beauty came from’. And this longing for Eden, as Lewis’s friend J R R Tolkien told his son, is ‘our whole nature at its best and least corrupted, its gentlest and most human.’ Perhaps the immortalists, in their quest to live forever and to ‘end the separation between people’ are longing for these things, too; they’re just doing it in a different language.

But they’re also, I think, pointing in a different direction. Sure, I’d love to live long enough to meet my great-great-grandchildren, and if I can’t, I hope that my children live to meet theirs. Yet I also hope that this won’t cause them – cause us – to deny the bittersweet nature of the human condition. The immortalists believe that beating death will reveal the road to peace and harmony. And I believe exactly the opposite: that sorrow, longing and maybe even mortality itself are a unifying force, a pathway to love. We don’t welcome them. We certainly don’t enjoy them. But, in the end, it’s life’s very fragility that has the power to connect us all.

Extracted from the book Bittersweet: How Sorrow and Longing Make Us Whole (Penguin Random House, 2022) by Susan Cain.