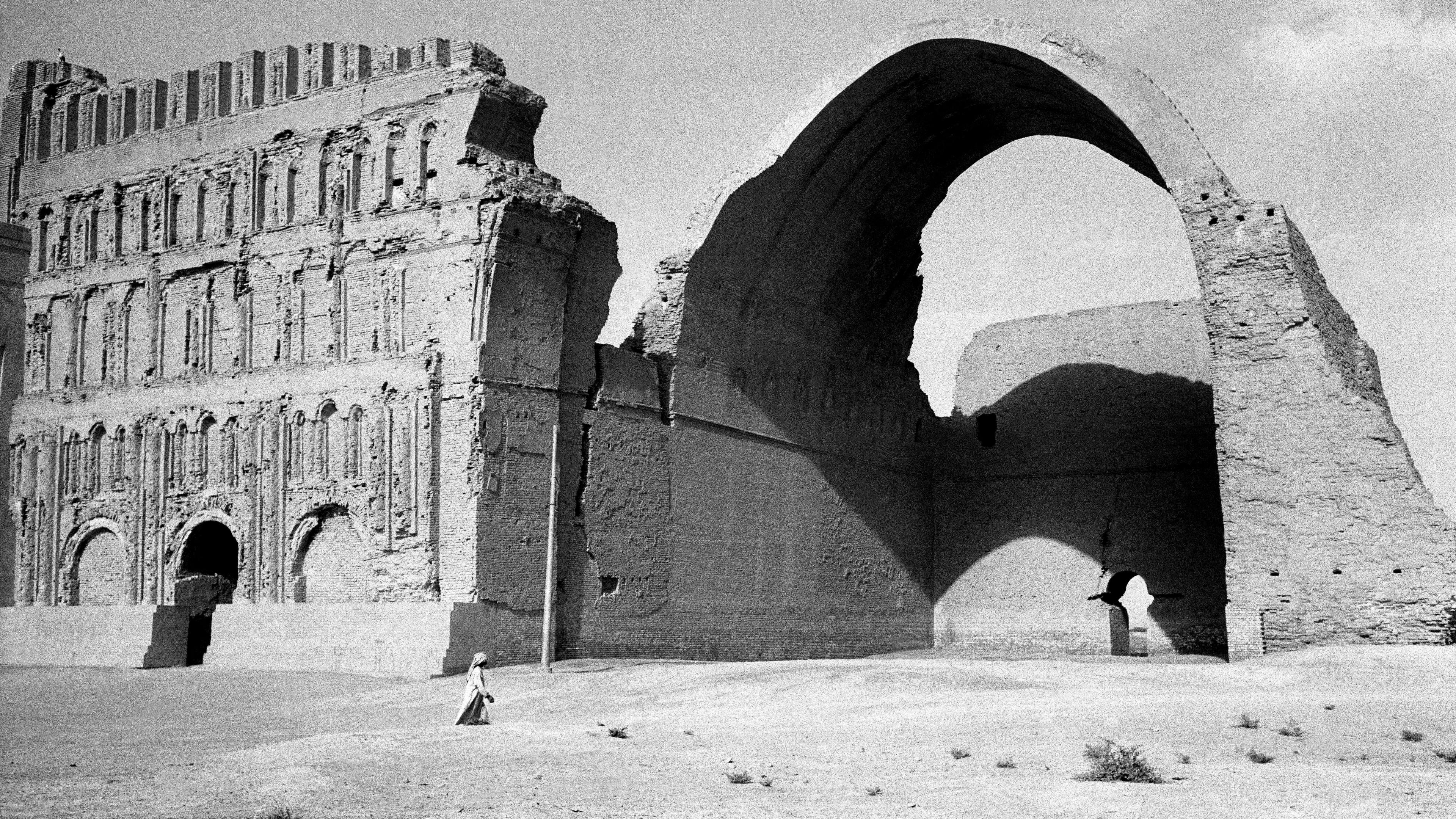

Along a dried-up channel of the Euphrates river in modern-day Iraq, broken mud bricks poke out of vast, dusty ruins. They are the remains of Uruk, the birthplace of writing that’s better known in popular culture today as the city once ruled by the legendary king Gilgamesh, the hero of an epic about his struggle with life, love and death. Sometimes called the oldest story in the world, the Epic of Gilgamesh continues to resonate with modern audiences more than 3,000 years after a Babylonian scholar named Sîn-leqi-unninni picked up his reed stylus and, in the tiny tetrahedrons of cuneiform script, impressed a standardised version of the epic on to 12 clay tablets. Written in a literary dialect of the Akkadian language spoken in ancient Mesopotamia, it’s this version that has survived on fragmentary clay copies – some as big as an iPad and others as little as a fingertip – uncovered from sites throughout what is now Iraq, Syria and neighbouring countries.

The story is equal parts hero’s journey and crash course in Mesopotamian cosmology, as Gilgamesh follows the Tigris and Euphrates rivers to their source beyond the known world in search of a survivor of the apocalyptic Flood named Uta-napishti. Fundamentally, it tells of Gilgamesh’s transformation from cruel to kindly king. Central to this is his relationship with Enkidu, a wild man who was sent by the gods to temper Gilgamesh’s tyrannical rule, and who becomes his closest friend and lover. The pair undertake a series of adventures together that culminates in their slaughtering of the Bull of Heaven, a fiery creature plucked from the constellation Taurus. For this act, the gods decide to punish them by taking Enkidu’s life and, in many ways, this is where the epic begins, as Enkidu’s death launches Gilgamesh’s quest for the antediluvian secret to immortality. That quest sees him traverse the mythical landscape of ancient Mesopotamia and the region’s linguistic landscape of emotional distress. Following Gilgamesh’s journey reminds anyone who has ever grieved that they’re not alone – the experience of extreme loss transcends the millennia-long gap between what it meant to be human then and what it means now.

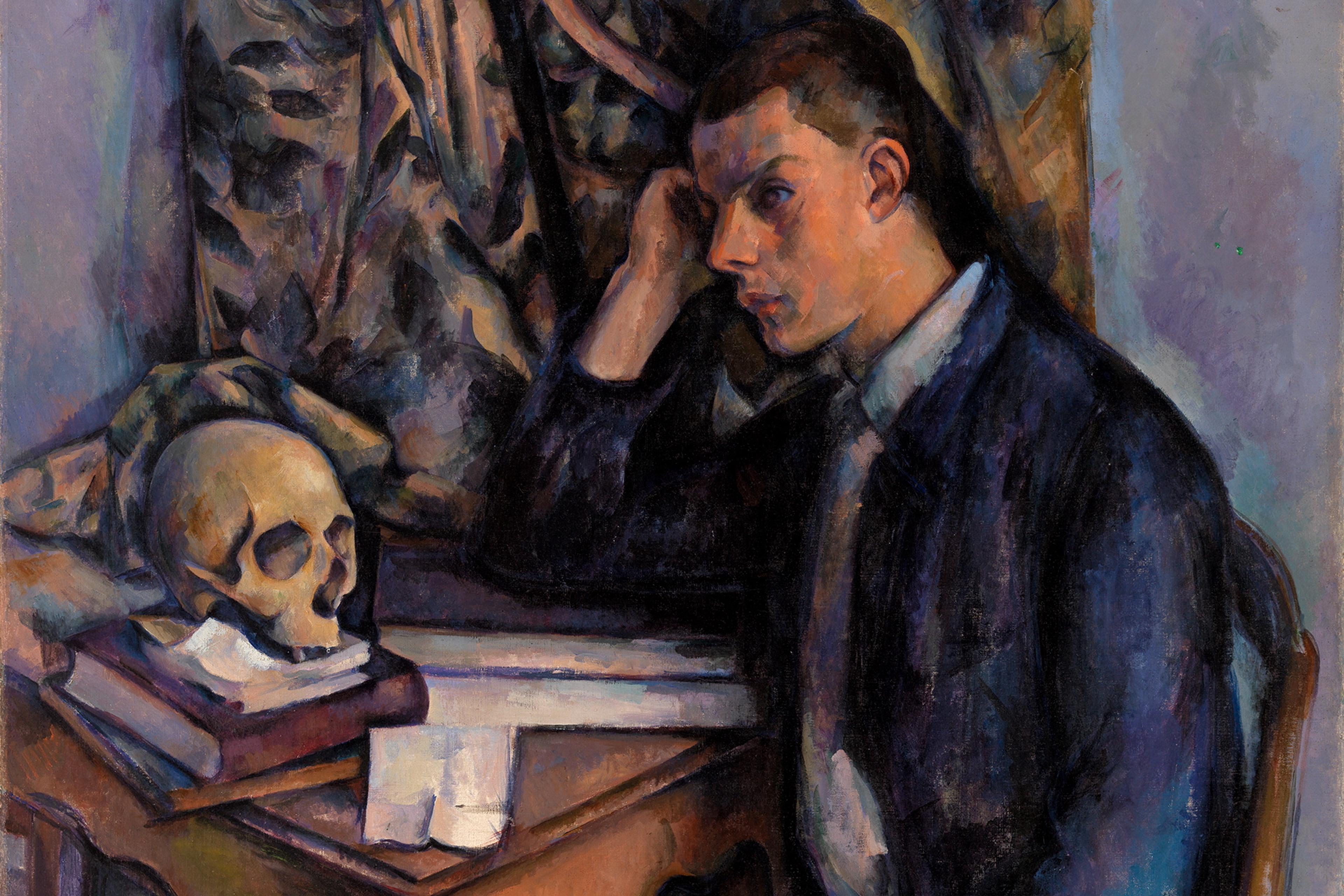

Gilgamesh’s initial reaction to Enkidu’s death is a heart-rending picture of misery. Staring at the fresh body, he screams: ‘Now what sleep has seized you?’ and reaches out to feel for a heartbeat. When he finds nothing, he pulls a veil over Enkidu’s face. He paces back and forth like a lioness who has lost her cubs, he pulls out his hair and tears off his clothes. For seven days and nights, he weeps over Enkidu and refuses to allow him to be taken for burial until a maggot crawls out of the decomposing corpse’s nose. Following an elaborate funeral, he continues to weep bitterly and takes to roaming the wild steppe outside Uruk’s walls. ‘Sorrow has entered my belly,’ he declares. ‘I became afraid of death and go wandering the wild.’ Anyone who has suffered the pain of loss will see themselves in this scene.

The initial language of Gilgamesh’s grief tallies with established mourning responses and rituals of the time, including weeping, wailing, tearing at one’s hair and clothes, and separating oneself from civilisation until the process is completed. Gilgamesh’s wandering in particular evokes a motif of distress in ancient Mesopotamia as portrayed in the era’s medical texts. One composed around the same time as Sîn-leqi-unninni’s version of Gilgamesh, the cuneiform Diagnostic Handbook, or Sakikkû as it was known in antiquity, describes over the course of 40 clay tablets ailments as varied as seizures and skin lesions. A depressed state, fever, weeping, nausea and unintelligible speech are described in a fragmentary section of the seventh tablet, together with ‘wandering about regularly’. A much later scholarly exegesis on that section equates ‘wandering about regularly’ with ‘madness’. Gilgamesh’s grief overlaps with the vocabulary of emotional distress in medical texts to provide a glimpse of what people, from legendary kings to anonymous patients, did when they felt sad. They wept, they wailed, they wandered, and at some point, they sought help – typically from a physician in lieu of a distant, primordial man.

Gilgamesh’s wandering not only betrays his inner turmoil but also spurs his quest for the secret to immortal life, inspired partly by his grief and partly by his fear of meeting Enkidu’s fate. Who better to learn this secret from than his antediluvian ancestor, Uta-napishti, who lives beyond the borders of the known world at the mythical ‘mouth of the two rivers’ (Tigris and Euphrates). To get there, Gilgamesh must pass through Mount Mashu, the horizon’s cosmic gates where the sun god rises and sets. Two monstrous half-human, half-scorpion sentinels guard the sun, and Gilgamesh must talk his way past them. The surviving fragments of the epic preserve the last few lines of his speech, a broken reference to his ‘sorrow’ and ‘exhaustion’.

There is no shortage of words in Akkadian that express sorrow. The one used here, nissatu, is the same one used to refer to the wailing that people do in mourning rituals and to a type of severe depression for which people received medical therapies of the time. A long compilation of these various therapies given to improve a patient’s happiness was unearthed in a house in Ashur, a city along the Tigris River that served as the capital of the Assyrian empire for more than 1,000 years. It’s part of a collection of tablets belonging to a medical exorcist named Kisir-Ashur and includes instructions for a herbal treatment ‘so that sorrow may not approach a man’. (The same Akkadian word, nissatu, also finds its way into medical therapies as a drug whose name translates literally to ‘plant for sorrow’, which the early British cuneiformist R Campbell Thompson once provisionally identified with cannabis, given its use on depressed patients.)

Whatever Gilgamesh says about his sorrow and exhaustion convinces the scorpion-people to let him pass into a pitch-black region beyond Mount Mashu that takes exactly 12 hours to traverse. In transcending this region, Gilgamesh exits the limits of the known world and enters a terra incognita in Mesopotamian cosmic geography. He emerges on to a grove of gemstone-studded trees – with carnelian, lapis-lazuli and coral in full bloom – that he walks through to reach the seashore. There, he finds an inn run by a woman named Shiduri who knows the way to Uta-napishti. Upon seeing the tired hero, she reprises Gilgamesh’s own earlier declaration when she asks: ‘Why is there sorrow in your belly?’ In Sîn-leqi-unninni’s version, he replies by asking why, after all he has been through, there shouldn’t be.

A more ancient version of the epic locates Gilgamesh’s sorrow not in his belly, but in the heart. ‘My heart is sick for my friend,’ he says to the innkeeper, ‘my heart is sick for Enkidu.’ The heart, or libbu in Akkadian, is the organ of thought and emotion that can ponder, plot, talk, and feel. As today, it can also experience a range of orientations and moods when things go wrong. In the early 1950s, a group of Turkish and British archaeologists excavated an Assyrian site known today as Sultantepe that yielded about 400 tablets written by a family of scholar-priests between 718 BCE and 611 BCE. One of the tablets describes a patient whose heart feels frightened, is depressed and ponders foolishness. The treatment is a complex ritual involving, among other things, pouring hot bitumen over figurines of the witches blamed for the illness.

The heart, as we know, can also be broken. In a cuneiform medical tablet from the 7th-century BCE library of the last great Assyrian king Ashurbanipal, a person with a broken heart also feels irritable, looks gloomy and suffers from low libido. A similar medical text from nearby Ashur describes heartbreak with symptoms such as terror and fear, while another adds grief and foolish thoughts, which also originate in the heart. A letter from a physician named Nabû-tabni-usur complains about his stress while serving in the royal court around the time of king Ashurbanipal. ‘While all my associates are happy,’ he writes, ‘I am dying of a broken heart.’ If you were anxious or depressed in ancient Mesopotamia, you were said to suffer from heartbreak. Distilled from the hundreds of thousands of surviving cuneiform texts, the heartsick Gilgamesh and broken-hearted Nabû-tabni-usur use expressions for sorrow and stress that still resonate today. Far from the modern luxuries they are sometimes made out to be, these sorrows and stresses are experiences as ancient as they are human.

Returning to Gilgamesh’s journey, Shiduri the innkeeper eventually relents to his demands and directs the hero to the ‘waters of death’ that he must cross to find Uta-napishti. As Shiduri did earlier, Uta-napishti too notes Gilgamesh’s wild and wretched appearance, like one filled with grief who has wandered far from his city. We can imagine a bearded old man, shaking his head at the young hero before him and asking: ‘Why, Gilgamesh, do you constantly chase sorrow?’ This nissatu has followed Gilgamesh from the start of his journey in Uruk to the world beyond the horizon and, by following his journey, we’re witnessing some of the earliest known expressions of human suffering.

Gilgamesh hopes to receive everlasting life from Uta-napishti but instead the ancestor tells the hero that wandering in search of this unattainable goal is actually shortening his life. For humans, he tells Gilgamesh, the gods established both life, which is fragile, and death, which can strike at any time. ‘No one sees the face of death,’ he reminds Gilgamesh, ‘no one hears the voice of death, and yet furious death is the one who cuts man down.’ Death is inevitable. Eternal life lies not in the survival of Enkidu, Gilgamesh or any other individual, but in the survival of the community.

Although the hero’s search for immortality ultimately proves futile, he gains instead the wisdom to accept that all life must come to an end, and that the best way to preserve Enkidu’s memory, and ultimately his own, is to be a good king who protects the lives of his subjects. He can finally stop mourning and move on. Upon his return to Uruk, Gilgamesh chisels his account into a stone tablet and embeds it into the brickwork of the city walls for someone to find some day.

The last known manuscript of the Epic of Gilgamesh from antiquity was written by an astronomer-in-training named Bel-ahhe-usur in 130 BCE, but Gilgamesh’s memory didn’t die with that tablet’s final tiny wedge. The legendary king would be happy to learn that after thousands of years, he and Enkidu have been resurrected in an enduring story about sorrow, searching and, ultimately, healing. The millennia-old epic reminds us that making sense of grief is as old as the oldest writing in the world, and that a tragic but inescapable part of being human is learning to live without the ones we love.