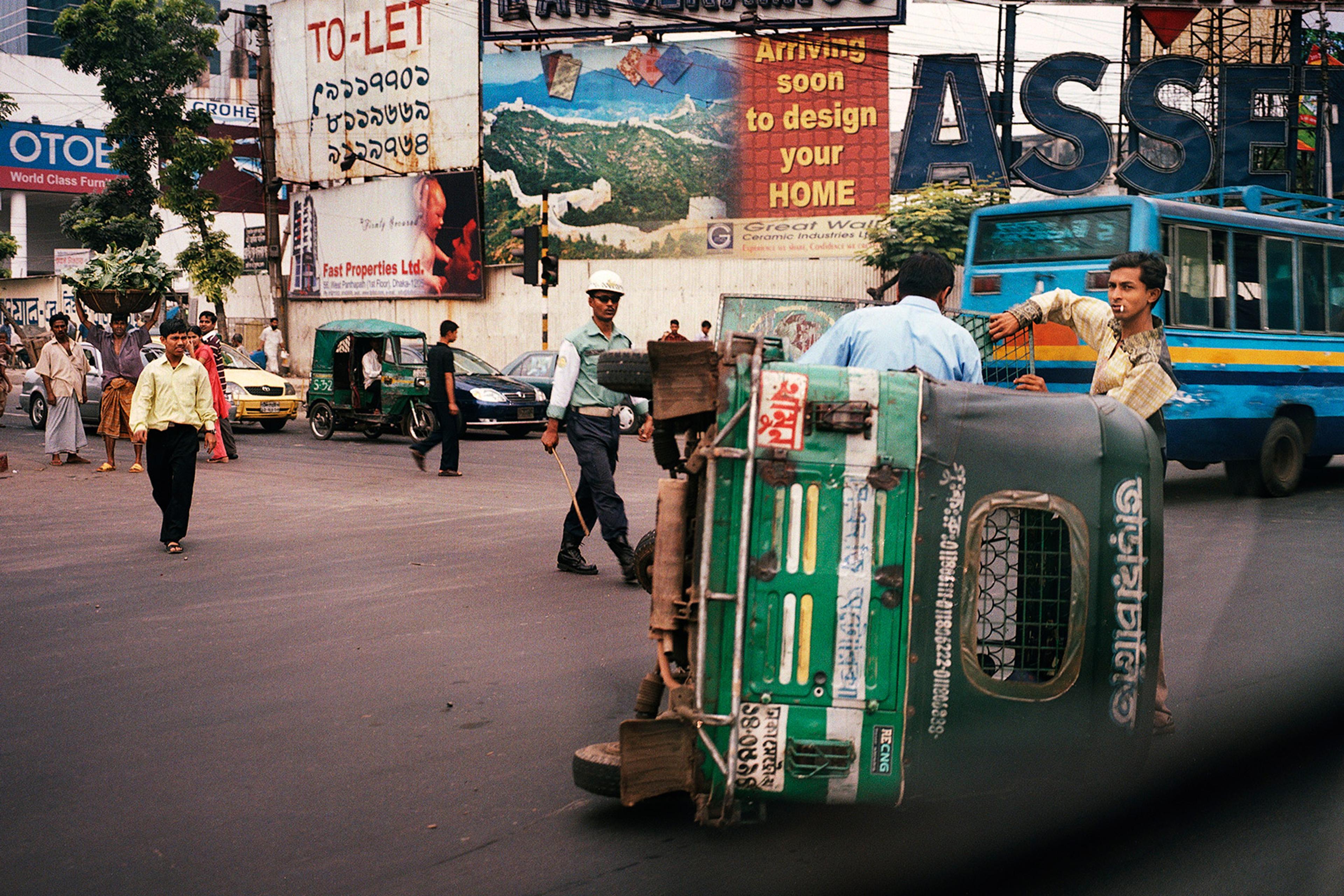

Every day, each of us makes countless evaluations. Is the coffee you’re drinking one you would buy again? Is it worth going to the gym today? Should you speak up in a meeting or stay silent? How you respond to questions like these is influenced by how positively or negatively you feel about an object, such as your coffee, or an action, such as speaking up. These judgments guide your behaviour, often without you even realising it. But not all evaluations are of the same kind. And our research finds that the mode in which you think about how good or bad something is – what, exactly, ‘good’ or ‘bad’ means to you in any given moment – can lead to radically different conclusions.

If you evaluate something in moral terms – based on what’s right or wrong, and rooted in social norms and values – your judgment is likely to become loaded with emotion and feel more extreme. Moral concerns can make someone more committed to their evaluation, as well as less tolerant of people who hold different views. A contrasting mode of evaluation is pragmatic: weighing the practical costs and benefits. For example, in the pragmatic sense, carpooling might seem like a good thing because it saves money and reduces the mileage on your vehicle. Finally, hedonic evaluation focuses on pleasure or pain, how something makes you feel in the moment. Eating a chocolate chip cookie might seem good in this sense because of its delicious taste, regardless of other considerations.

Whether you rely more on a pragmatic, hedonic or moral perspective to evaluate an object or action depends on multiple considerations, including your goals and the social context. The way you look at a problem might change based on how you feel at that moment, or whether you are alone or accompanied by a friend. And this can fundamentally change how you judge the goodness of something.

We recently encountered this dilemma when meeting up for coffee to discuss our research. The decision about where to buy a coffee can be based on pragmatic considerations (eg, which café has the cheapest prices?), hedonic ones (eg, which café has the most delicious coffee?), or moral ones (eg, is the café ethical in the way they treat their staff?) In fact, where we went to buy a latte differed depending on which mode of evaluation we used. The cheapest café was a little hole in the wall a block north of our office, the most delicious latte was a short walk west across the park, and the café with the most upstanding sense of ethics was one block south of the psychology department.

Our decision about where to go hinged less on the coffee and more on how we initially chose to think about the decision itself. As neuroscientists, we wondered how the brain puzzles through such seemingly simple decisions.

We and our collaborators decided to run a study to investigate how different types of evaluation – moral, pragmatic, and hedonic – are processed in the brain. Do they stem from a common evaluation system, one that incorporates different information depending on our goals? Alternatively, different evaluations could result from distinct evaluation systems that rely on different brain regions. Maybe moral evaluations are fundamentally different from pragmatic evaluations. Examining this question at the level of the brain allows us to look under the hood for underlying mechanisms that may not be evident from behaviour alone. In this way, neural evidence can help us get closer to the essence of these evaluative processes. This might give us clues about why people make the decisions they do.

So, we invited participants from New York University to make their own judgments inside a magnetic resonance scanner as we recorded their brain activity. They were asked to evaluate 84 different kinds of actions – such as lying to a friend, voting, or recycling – rating on a scale how good or bad they thought each action was. Critically, we asked each person to switch how they evaluated each action by instructing them to focus on either its moral, pragmatic or hedonic aspects. Thus, people ultimately evaluated the same actions three times, using the three types of evaluation. We then compared how their brain responded to the same actions when using a moral, a pragmatic or a hedonic perspective.

Moral judgments tend to amplify emotional responses, often driving behaviour more powerfully than other types of evaluations

A moral framing often evoked the strongest and most polarised judgments. For example, participants’ ratings of getting a flu shot were significantly more extreme – whether in a positive or negative direction – when they were asked to evaluate it morally, compared with when they evaluated it pragmatically or hedonically. This aligns with our prior research finding that moral judgments tend to amplify emotional responses, as well as other work showing that morality often drives behaviour more powerfully than other types of evaluations.

Our research also uncovered that these different modes of evaluation are based on overlapping neural systems. The brain operates as a hybrid evaluation machine: it relies on some shared regions in making each evaluation, while also engaging specialised areas depending on the type of judgment being made.

One of the shared regions is the amygdala, a structure deeply involved in processing emotional salience. Whether one is making a moral, pragmatic or hedonic judgment, the amygdala seems to flag the importance of the decision. Another shared region is the insula, which integrates bodily sensations and emotional experiences, and appears to play a key role in how one perceives the goodness or badness of something. A third structure at work in all three types of evaluations is the hippocampus, which draws on memory to help predict, based on past experience, what would happen if one chose to do something.

These results challenge the idea that the three types of evaluations are categorically different. Instead, they all seem to draw on some similar affective and experiential processes, even in domains that might seem more abstract or principled, such as morality, or more objective, such as pragmatism.

Yet each mode of evaluation activates distinct areas of the brain as well. Moral evaluations, as compared with pragmatic evaluations, involve greater neural activation in higher-order brain regions such as the orbitofrontal cortex and the cingulate cortex. When you make a decision, the orbitofrontal cortex allows you to consider aspects of a situation that carry emotional value – such as whether you expect others to see you in a more positive light for choosing ethically sourced coffee. The cingulate cortex then collects this input, combines it with information on your past emotional experiences from the hippocampus, and turns it into a plan for action. At that point, you might decide to pay a bit more to purchase a more sustainable cup of coffee.

Compared with hedonic evaluations, moral evaluations more strongly activate a brain area called the temporoparietal junction. When you see a hand holding a cup of coffee, this area allows you to distinguish whether that hand is yours or someone else’s. Similarly, when you sense an emotion, this region helps you identify if it’s yours or not. The temporoparietal junction is very helpful in overcoming egocentric views and recognising others’ needs and intentions. This is precisely what’s needed when it comes to thinking beyond your own immediate desires and supporting others. Accordingly, neural circuits that support moral evaluations carry information about others’ needs, while hedonic evaluations seem to be more self-centred, as they are focused more narrowly on maximising your own pleasure and minimising your pain.

Psychologists have been torn over whether morality is ‘special’ or not

All in all, moral, pragmatic and hedonic evaluations each depend on brain areas that compute how positively or negatively you feel about something based on your previous experiences. This suggests that at their core, all these evaluations may be grounded in a common affective currency, a shared system for representing value shaped by memory and emotion. On top of that, moral evaluations activate social components related to others’ needs and how others may view you.

It seems, then, that moral evaluation is not an entirely separate process or module in the brain, but a variation of the same basic evaluative system, focused on the social implications of an action. These findings support a hybrid view of evaluation, offering a bridge between psychological models that emphasise general-purpose evaluation and those that include domain-specific systems or modules. This is important because the fields of psychology and neuroscience have long debated whether the mind is modular or generalised. For example, psychologists have been torn over whether morality is ‘special’ or not. Our data suggest that both sides of these debates have merit. And the activation or deactivation of additional components, in shifting between a moral and a pragmatic or hedonic perspective, depends on your goals and the situation you find yourself in.

Understanding better how people evaluate goodness and badness has implications for everyday life. Imagine you’re considering whether to call a friend who’s sick. In hedonic terms, you might anticipate that you’ll feel good while chatting with your friend (or, conversely, you might dread an emotionally heavy conversation). If you’re evaluating it pragmatically, you might question whether you have time right now for a call. And yet, if you’re thinking morally, you might feel a sense of obligation because reaching out to a friend in need is the right thing to do. Each mode of evaluation brings a different perspective and can lead to very different preferences. Knowing that these modes rely on partly different brain areas, you might decide to deliberately shift your evaluative lens – or intentionally balance different perspectives – to better align with your most important goals and values.

You can also imagine how these differences matter in a group context or at work. Let’s say you’re in a meeting, deciding whether to speak up about something you disagree with. Pragmatically, you might weigh the potential career benefits against the risk of criticism. Hedonically, you might worry about the discomfort of confrontation. Morally, you might feel compelled to raise an issue because it clashes with your values. Being aware of these different modes of evaluation could help you notice when one mode is dominating the others, or when you are being manipulated to think through a certain lens, even though it may not be the most appropriate one.

The philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah writes, in Experiments in Ethics (2008), that ‘the act of framing – the act of describing a situation and thus of determining that there’s a decision to be made – is itself a moral task.’ As we make our constant stream of evaluations in day-to-day life, the burden is on us to think carefully about how to frame them.