‘Why do you love me?’

After many years, I have come to think this is an ill-formed question. Ill-formed for many reasons, not the least of which might be that it has no good answer. ‘Because you are strong; because you are attractive; because you make me laugh; because you are kind; because you will be a great father; because you are (financially or otherwise) stable; because you are great in bed; because you make me feel complete; because you are confident, tranquil, young, fun, creative, smart, composed…’ Ad nauseam.

I guess I thought – for a very long time – that there was a very good reason to love one another. And this belief also made me think that the point of life was to make oneself lovable. I would go to the gym – to be lovable. I would write great books – to be loveable. And I would hold myself together, as best as humanly possible – to be loveable. Of course, I should have known that this was a largely futile project. At the end of the (very long) day, I felt out of shape, ugly, poor and vulnerable. Probably, at root, because I had the misguided belief that the question ‘Why do you love me?’ could have an adequate answer.

If you do believe that there is a reason to love – trust me, you will spend your life looking for it. And from a man who has been married three times, again believe me, it will destroy any and all chances for true intimacy. If you tacitly think that you have to be a certain way to satisfy love’s conditions, you will dedicate your life to it, and, most likely, waste it in the process. I spent so many hours in the gym, on the treadmill, in the library – thinking that all of this was going to pay off. And I spent so much of my life scrutinising others – most especially my closest intimates – to see whether they measured up. Not realising that love is not a matter of debt and exchange.

You can imagine a couple in love – for five or seven years – arriving at dinner one night, on a night without kids or responsibilities, without much to say, and without much to do. The husband says ‘I love you’ in exactly the way that says ‘Do you love me?’

And the wife, she smiles broadly. ‘Of course!’ she says.

She clears her throat to explain: ‘I love you because you are so kind to me in hard times – and always there for me when I am sad.’

The husband nods and acts satisfied, but he wouldn’t be. Surely there had to be better (or at least more extensive) reasons than this. This is it? And in the back of his head, he would have the more disturbing thought that his wife was really just lying to him: three days ago, she had swung into an inconsolable mood, a true unspeakable funk, and he… he had been nothing like kind or supportive.

What we want in love and life and marriage is something of incomparable worth

In truth, there is probably no good reason his wife could furnish. Because there is no good reason to love him – or me, or you. Because there is no good reason to love. An exhaustive list of love’s conditions cannot be assembled. Just as an exhaustive list of characteristics cannot fully describe yourself, or just as an exhaustive list of possibilities cannot define your future. This is for the best. If you don’t believe me, let’s take a second to consider Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s ode to unreasonable passions:

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

I love thee to the depth and breadth and height

My soul can reach, when feeling out of sight

For the ends of being and ideal grace.

I love thee to the level of every day’s

Most quiet need, by sun and candle-light.

I love thee freely, as men strive for right.

I love thee purely, as they turn from praise.

I love thee with the passion put to use

In my old griefs, and with my childhood’s faith.

I love thee with a love I seemed to lose

With my lost saints. I love thee with the breath,

Smiles, tears, of all my life; and, if God choose,

I shall but love thee better after death.

The poet never says ‘I love you because –.’ She doesn’t ask ‘how do I love thee’ and then give extensive reasons. That would be rather dissatisfying, wouldn’t it? Love is not to be earned or bartered, because if it were then it would be something of comparable, and not incomparable, worth. And that’s what we want in love and life and marriage, something of incomparable worth. So we should get it through our heads – there is no reason to love one another. In the words of the monk and poet Thomas Merton, ‘love is not a package’ to be measured, bartered and exchanged.

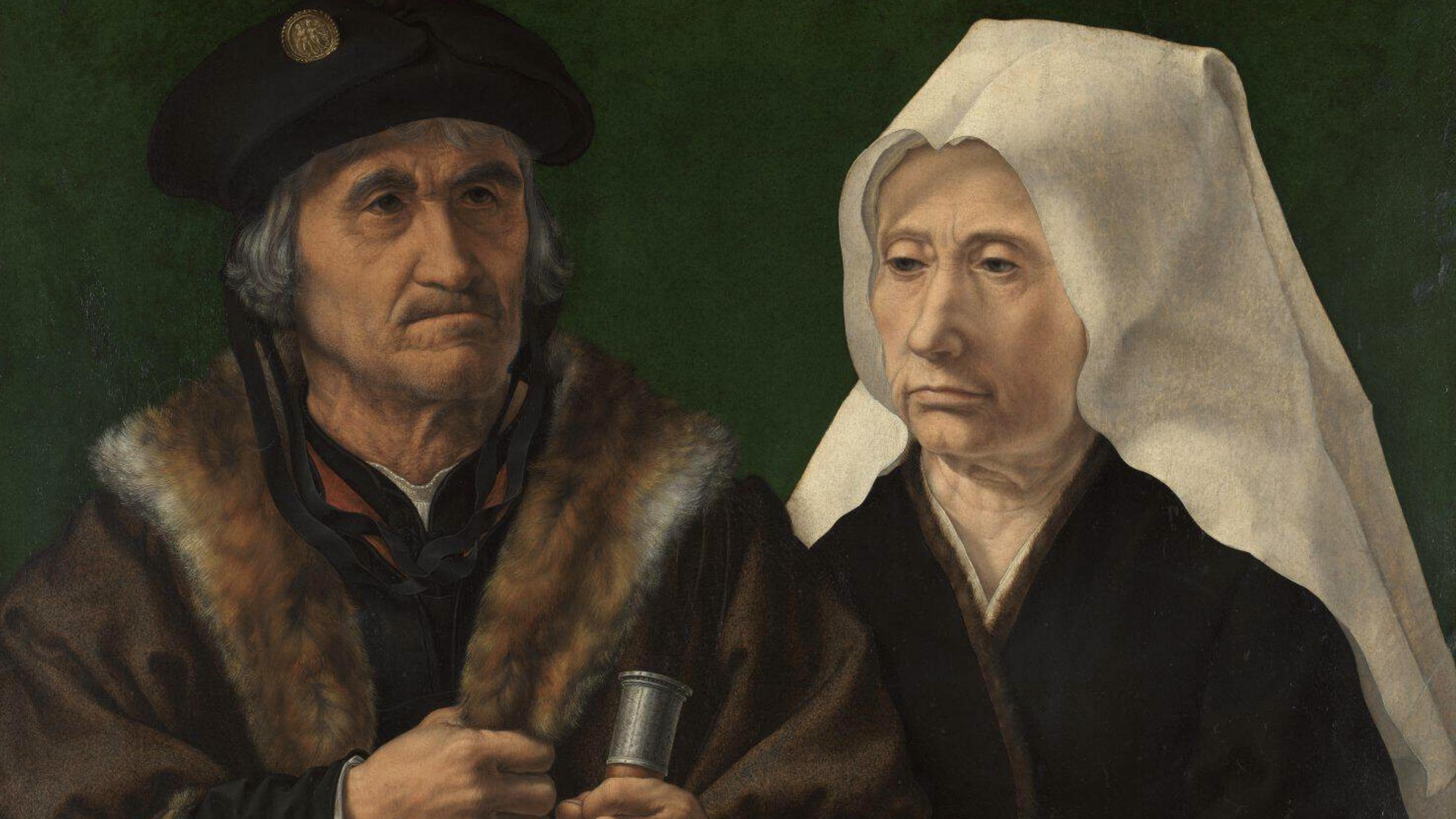

This might be counterintuitive but I promise it will turn out to be more right than not in the end. Because, in the end, we are all extremely unpleasant little beasts. We are unkind and short-tempered and disloyal, and altogether ugly – plus, we grow old, get sick and die – which is about the best reason that one could ever have to avoid loving little creatures like us. We could never, ever, in any number of lifetimes earn something like love. But we do love and are loved, and that unreasonable fact should provide a bit of peace of mind in several different respects, just so long as we take it to be wholly and utterly unreasonable. Loving (and especially getting married) is an unreasonable decision, and it has to be for love to survive.

When I was 40, I hopped off a treadmill in the gym at the university where I teach. I had just killed myself for nearly an hour, thinking that I was only worth something (in other words, was lovable) by submitting myself to its whirring belt. And then I actually died. The EMTs brought me back to life after a cardiac arrest, and I spent a year going through bypass surgery and convalescing in the most unbecoming of situations. My third (and, I swear, final) wife, Kathleen, had to help me to the bathroom, had to help me use the bathroom, had to help me out of bed, had to put up with my most unbearable mood. And it was the first time that I realised that you don’t love someone for any good reason – because I certainly wasn’t furnishing any. It was the greatest relief of my life.

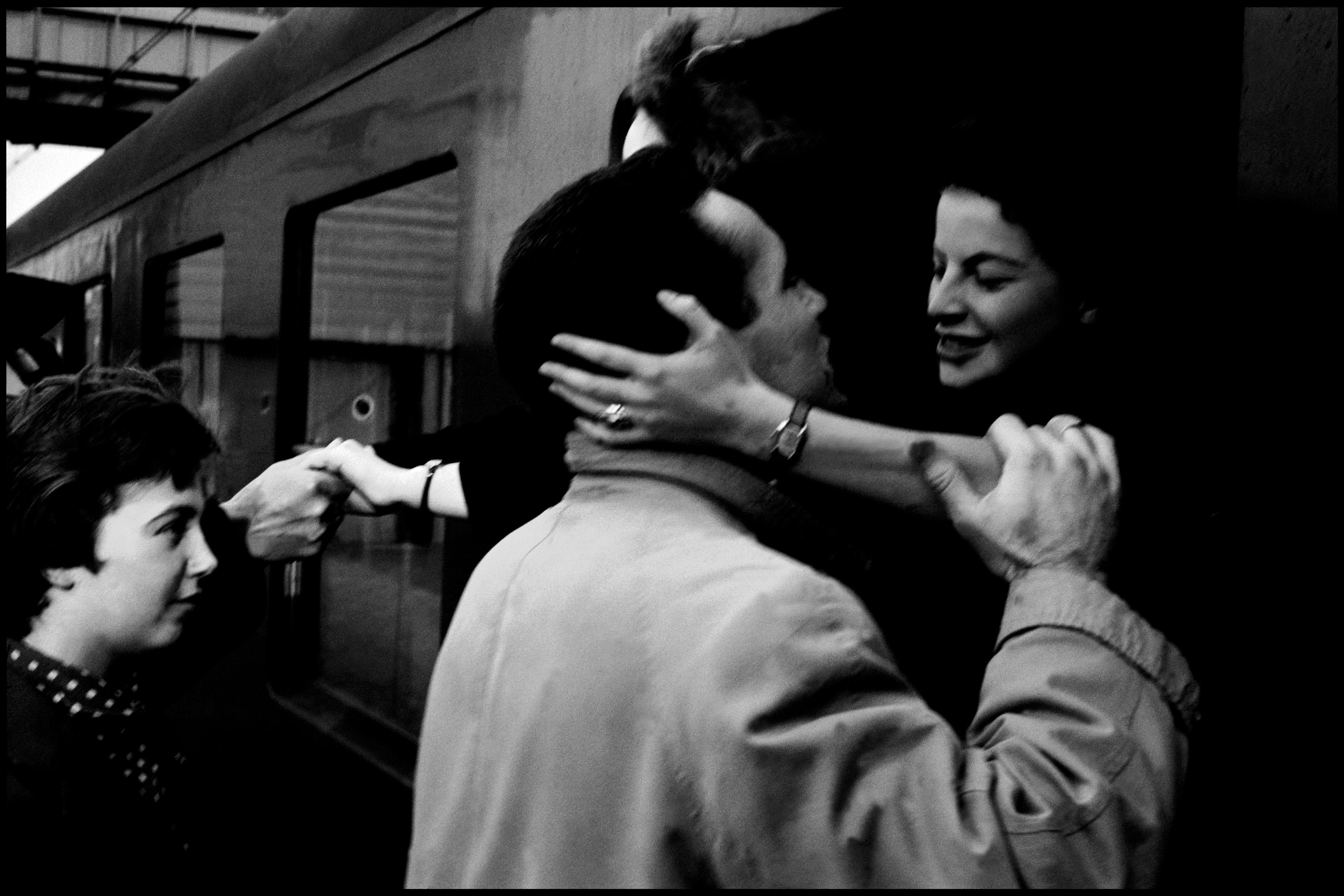

This is why making up after an argument can be so incredibly life changing. In this way, you (sometimes) prove that things can actually go to hell, and you still love each other, and that little miracle is so revelatory, so freeing, there are few acts that can embody it: laughing, singing, dancing, crying…

These activities in their purest forms are not forced, and they are neither compelled nor described accurately by any logical process. They are also, interestingly, not chosen, at least not in the typical sense of making a choice with a particular justification. In fact, if I present the reasons – extensive or compelling – for why a joke is so very funny, it becomes immediately less so. Tragic situations become less dire (thank God) in their therapeutic description. Dancing, or other acts that involve rhythm and beat, become mechanical and other-than-themselves when we think too carefully about their supposed rhyme and reason. Description has a way of destroying certain experiences. I take this as instructive. Having reasons is sometimes overrated, and maybe one of these sometimes is being in love. As Hannah Arendt once said of love, it ‘is killed, or rather extinguished, the moment it is displayed in public.’

Love is more akin to an act of faith than a rational decision

You might say that all of this is so obvious that none of it is worth mentioning. After all, we talk about ‘unconditional love’ like we already know what it means. But I would submit that we often speak with the most confidence about matters we regularly ignore, overlook and know nothing about. To say ‘I love you unconditionally’ frequently means ‘On balance, I will stay with you mostly, no matter what: I have weighed all the reasons that I love you and they will usually outweigh the reasons not to.’ As you can hear, this has everything to do with counting reasons and very little to do with love beyond measure.

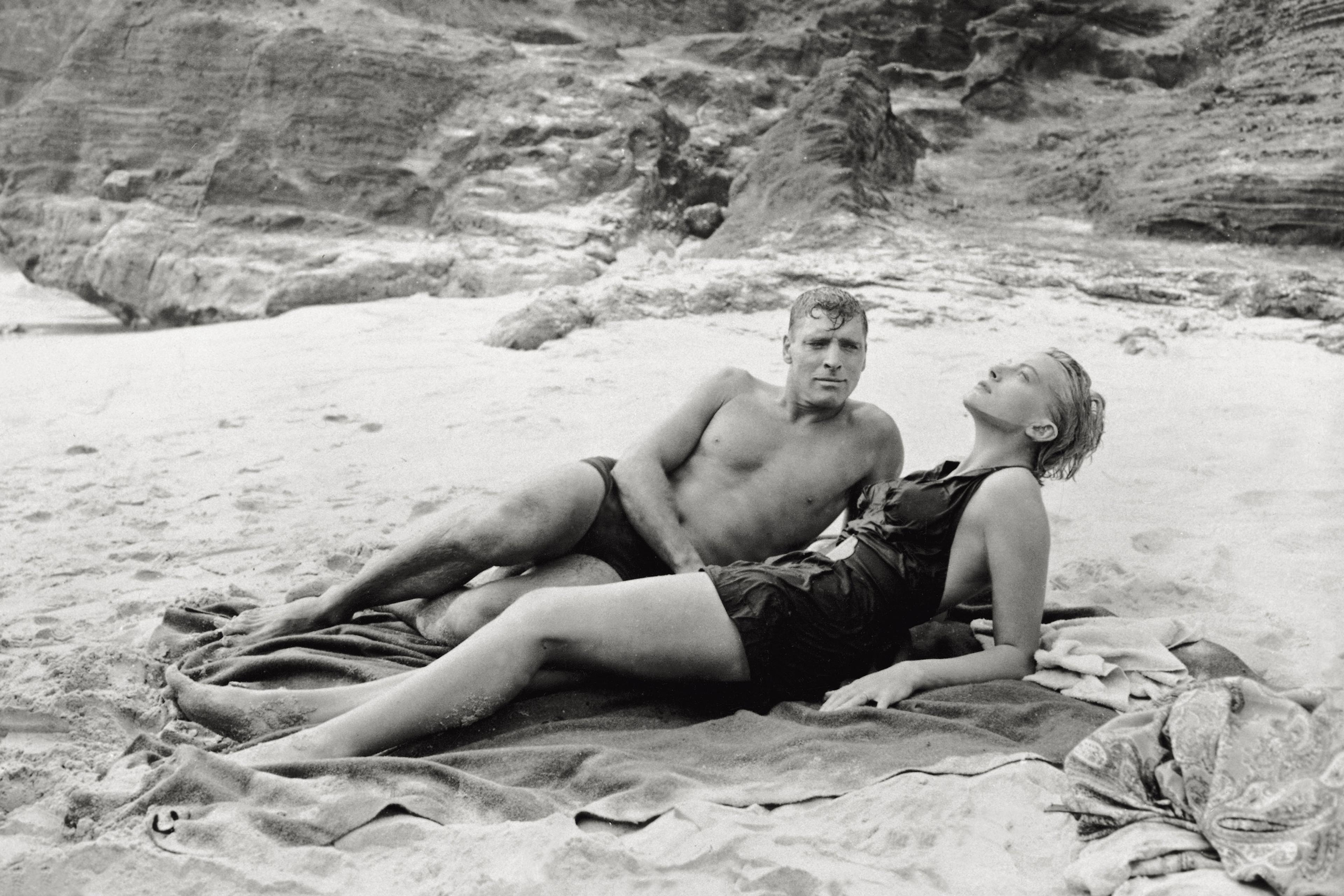

To say ‘I love you unconditionally’ is instead simply to say that there is no reason, neither good nor bad, for me to love you at all, that I do it freely without reason, in the same way that I laugh unexpectedly at this situation and not that. In this sense, love is more akin to an act of faith than a rational decision, and continues to be as long as we are ‘in it’. So let’s not forget, and it is easy to forget, the leaping into love or marriage is not a singular act, but rather remains as audacious (and irrational) as the initial fanfare of a wedding. Otherwise, it isn’t love.

One of my favourite poems is Emily Dickinson’s ‘Why Do I Love You, Sir?’ And the answer is just so terse, laconic, unreasonable – and right.

‘Why do I love’ you, Sir?

Because –

The Wind does not require the Grass

To answer – Wherefore when He pass

She cannot keep Her place.

Because He knows – and

Do not You –

And We know not –

Enough for Us

The Wisdom it be so –

The Lightning – never asked an Eye

Wherefore it shut – when He was by –

Because He knows it cannot speak –

And reasons not contained –

– Of Talk –

There be – preferred by Daintier Folk –

The Sunrise – Sire – compelleth Me –

Because He’s Sunrise – and I see –

Therefore – Then –

I love Thee –

So how do you fall out of love? It can never, I think, be by discovering that there is no reason left. Maybe we fall out of love when we confuse the conditions of companionship with love itself, which is, for better and for worse, unreasonable. Maybe we fall out of love just by thinking that we have to have the reasons to stay in.

Of course, there is another possibility, which is terrifying and therefore probably true. Maybe love ends as a song does: in its own time. Or as laughter fades, when the time is over. And maybe that is reason enough to be unspeakably grateful for the time that we have left.