One frigid evening this January, I dropped by the Outsider Art Fair in New York, a stripped-down event in its pandemic iteration, scattered across a few small galleries in the Bowery. At the Andrew Edlin Gallery, I was transfixed by some tiny talismanic drawings by Melvin ‘Milky’ Way, an artist with schizophrenia from South Carolina. Put together with Scotch tape, scraps of paper, marker and ballpoint pen, Way’s recursive considerations addressed a single theme: the precise structural formulae for the mysteries and marvels of human existence, from ‘sweet red cherry juice’ to ‘happiness’. ‘They’re all highly secret, not to be shared,’ explained a masked gallery assistant, adding that these small cards travelled in Way’s coat pocket as ‘weapons of protection’ through his years in New York’s homeless shelters and psychiatric facilities.

Clustered together on the wall, the densely patterned fragments recalled a museum display whose seals and tablets bore messages in a lost language from another time. Some contained a single pattern, such as purple whorls resembling a stained-glass window belonging to an occult temple. Some had insistent neologistic messages flashing alongside the chemical formula: ‘Compel, expulsate, perpetrate’ said one. Previous attempts to press Way on the meaning behind his work, including by the art critic Edward M Gómez, have resulted in disquisitions on the virtues of time travel, Way’s invention of cocaine, his purchase of Alaska, and the time he turned 16 – at the age of 60. Yet the unknowability of this art is part of its appeal. ‘Since [the artists] can’t explain their work, we’re left to discover it on our own,’ Edlin, the gallery owner, told me. ‘Their minds are impenetrable and, once you accept that, it’s liberating to just think of what the art means to you.’

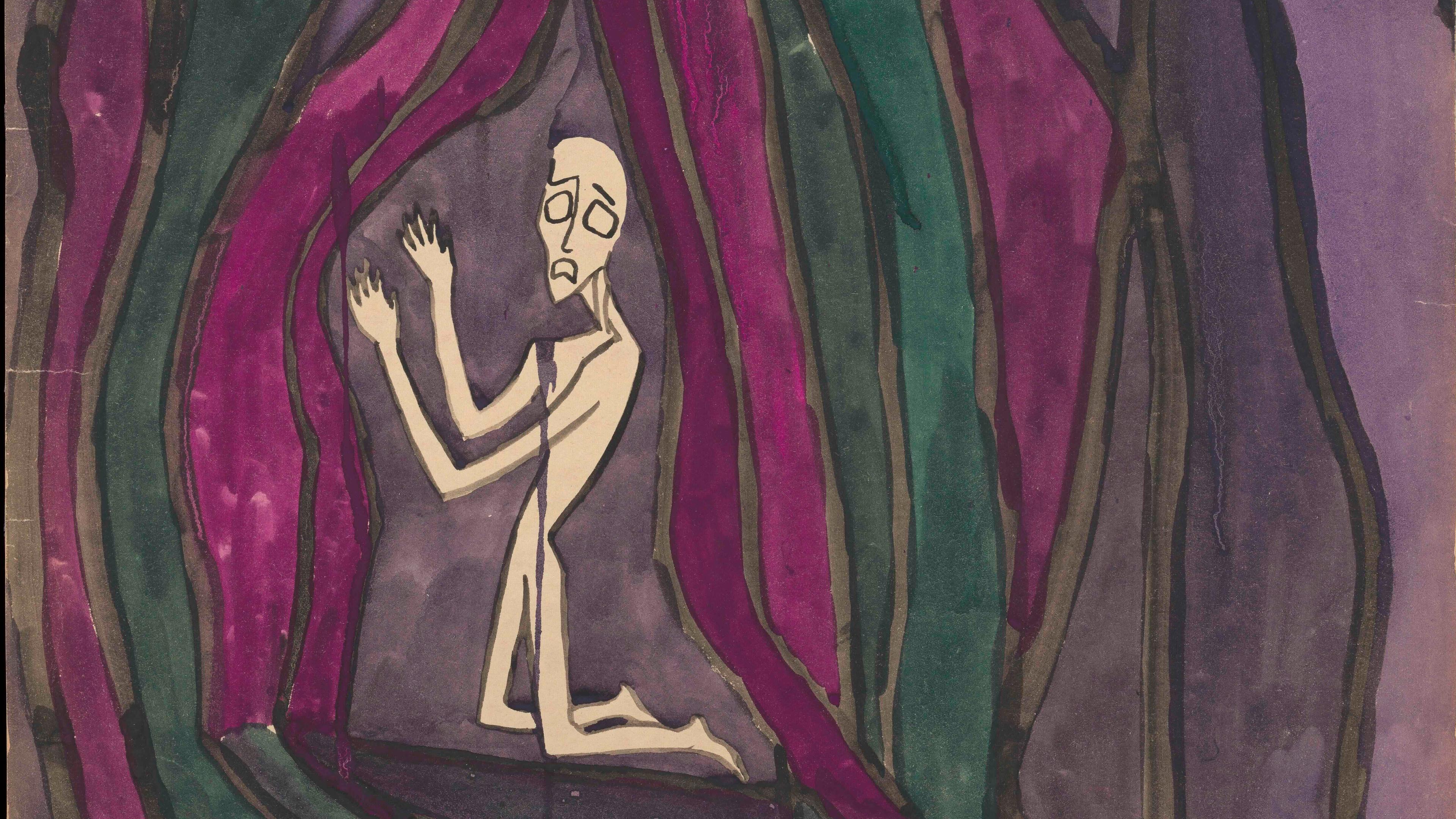

Every year, I seek out ‘impenetrable’ art at the Outsider Art Fair, the American Folk Art Museum in New York, and elsewhere. By now, I know what I’m drawn to: art that iteratively sketches out a personal obsession. It’s often heavily symbolic; swimming with a profusion of barely decipherable words, lists and astrological charts, or with hypnotic patterns of repeating concentric lines. In art made by erstwhile residents of psychiatric hospitals, sometimes the leitmotif is a home whose soaring windows and flowering plants speak of inexpressible yearning; sometimes, the drawings conjure a private hauntology, populated with beaked tormentors or looming, blackened wraiths with large, childlike eyes.

It’s not a straightforward, entirely kosher feeling to peer so closely at images that stream straight out of the cauldron of a lifetime of human pain, loneliness and ostracisation. Some of the artists are non-verbal, and their art is the closest form of locution they undertake in their entire life. Many have spent years sequestered in mental health units, or they’ve endured chronic bouts of sickness and indigence before their work posthumously changed hands for hundreds of thousands of dollars. Looking at this art head-on feels like glimpsing an optical illusion, or experiencing a psychic bait-and-switch. You can get lost in the immediate and surprising visceral pleasures of drawings compactly festooned with mysterious symbols and cursive text; in fantastical worlds rendered in coloured pencil; or the touchingly misshapen animals set in landscapes that are ever so slightly askew. Reading the biography of the artist can then plunge you into an abyss, or leave you both moved and discomfited, unsure how to feel about what you saw. Often, there’s a faintly queasy undertow of déjà venu: a sense of ‘I might have known this place, and, had the wind blown differently, I might have stayed there.’

Part-memoir, part-prayer, part-wish-fulfilment, part-tally of wordless anguish, this is art that evokes worlds unmoored from art-historical reference. Instead, it’s crowded with private fantasies, nightmares and sedulously embroidered or sequinned pop-cultural references. As Tom di Maria, the director of the Creative Growth Art Center in California, once told me: ‘These artists delight in ornamentation. They create a world of art so real they expect to live in it.’ And, as the first critic of psychiatric art, Marcel Réja, said more than 100 years earlier: these drawings represent ideographic writing; ‘a more concrete means of expressing [someone’s] thought, more alive than would be possible with the written word’. But such art is not readily comprehensible. Much as it’s crammed with meaning, it actively – innately – resists interpretation. This uneasy paradox lies at the heart of the appeal of psychiatric art.

The fascination with psychiatric art dates back to the late-19th century. As what were then called ‘lunatic asylums’ in England and Western Europe swelled in occupancy, a few gradually initiated collections of the spontaneous artwork – embroidery, sculpture, painting – created there. At the time, mental illness was considered an incurable brain disease, and asylums were custodial rather than therapeutic spaces: the patients were encouraged in their creative pursuits to stave off tedium. If not overlooked, the art they made was regarded as a translation of the illness in tangible form, and scrutinised by psychiatrists for tell-tale psychopathological signs.

The Swiss psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler’s formulation of schizophrenia in 1911 – as ‘a splitting of the psychic functions’, resulting in ‘associations which normal individuals will regard as incorrect, bizarre, and utterly unpredictable’, and caused by psychological processes rather than brain disease – cast the artistic output of asylum residents in new light. From a nosological aid, their work could be seen as providing glimpses of a ‘primordial’ source of the artistic impulse. This perspective was partly inspired by the book Genio e follia, or ‘Genius and Insanity’, (1864) by the Italian criminologist Cesare Lombroso. Lombroso believed that, in evolutionary terms, genius was a propitious type of madness, and that madness itself (also criminality) was a return to an earlier stage of evolution, via a process of ‘degeneration’. Lombroso scoured ‘typical’ artworks made by asylum patients for tell-tale marks of ‘atavism’ or ‘absurdity’. By linking genius and madness, he left an ominous legacy: if artistic geniuses could be discovered among the mentally ill, it followed that works of genius might in turn be marred by signs of ‘degeneracy’.

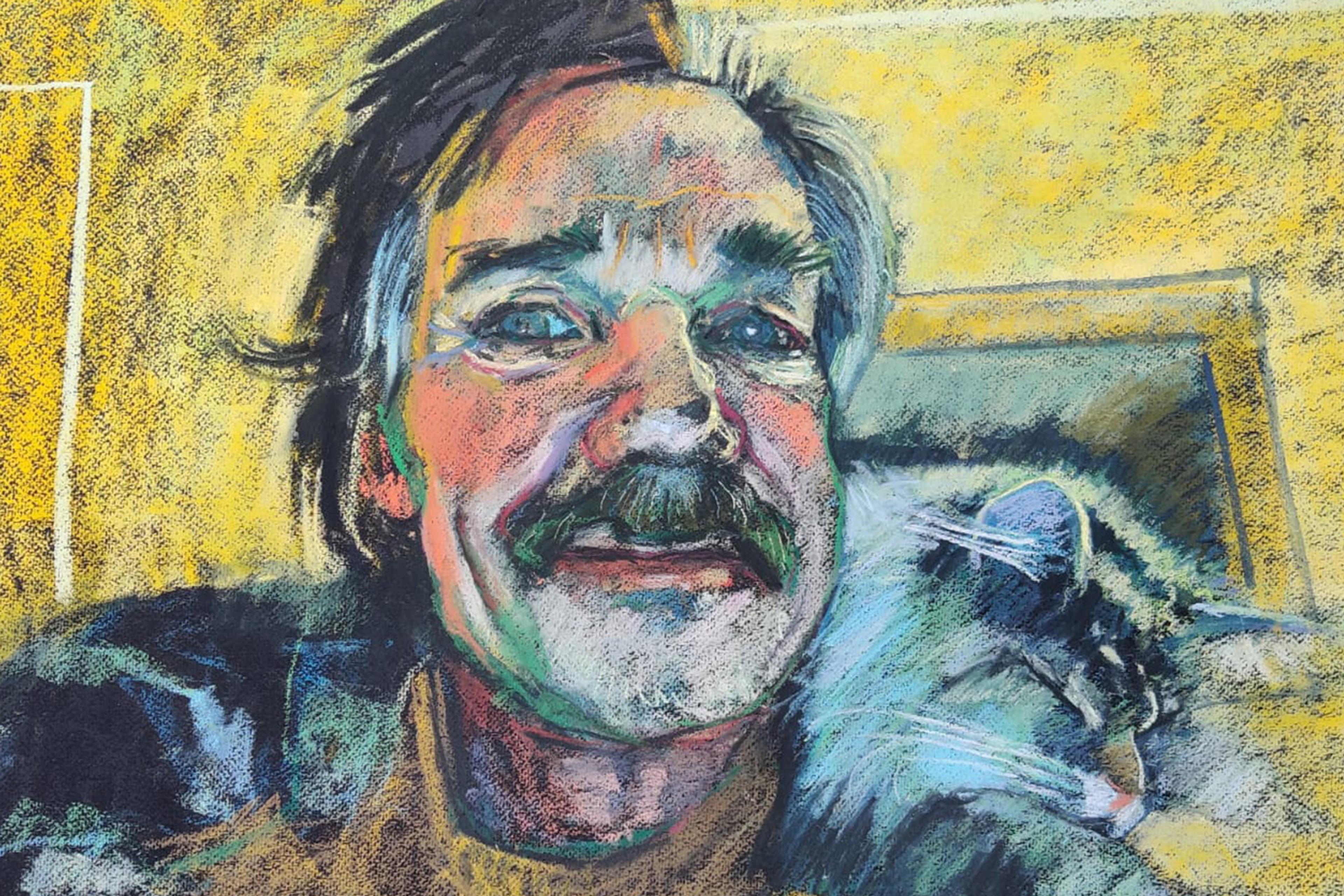

Over time, every asylum generated its own captive celebrity. From the psychiatric hospitals Bethlem in London and Broadmoor in Berkshire came Richard Dadd (a ‘criminal lunatic’ who was confined after committing patricide) whose intricate watercolour tapestries were filled with gnomes and fairies. The English artist Louis Wain, who was hospitalised with schizophrenia and paranoid delusions, enchanted London’s public with his stylised paintings of cats, while in Bern, Adolf Wölfli, a convicted paedophile who suffered from severe psychosis, used colour pencils and newsprint to create vast hallucinatory tapestries, swarming with mystic forms and repeating faces and patterns, around which unfurled musical notations to singular tunes that the artist would play on a paper trumpet.

Most of these artists were ‘discovered’ and championed by their resident psychiatrists. Wölfli’s psychiatrist, Walter Morgenthaler, produced the first monograph in the psychiatric art genre, A Mental Patient as Artist (1921). But the two doctors responsible for changing how everyone viewed such work were Marcel Réja and Hans Prinzhorn.

Réja was a poet, writer, theatre and dance critic who frequented Parisian Symbolist circles. He was also a doctor at the Villejuif Asylum – the first institution in Europe to collect its residents’ artwork, which it displayed at its ‘Musée de la Folie’, alongside prehistoric objects found on the hospital grounds. In L’art chez les fous, or ‘The Art of the Insane’, (1907), Réja presented patients’ artwork alongside examples of other art that was thought to emerge from close to the ‘source’ of the artistic impulse: art produced by children, prisoners, spiritualist mediums and ‘primitive’ sculptors from Africa and Oceania. For Réja, his patients’ art constituted a kind of ‘ideographic writing’ that was ‘more or less embryonic’. It disregarded academic tropes or pecuniary concerns. With its curious hierographic symbols and repeating geometric forms, he thought it harked back to more ‘primordial’ forms of creation, like the mysterious maps, animals and symbols that ancient people scratched into stone 35,000 years ago. Réja wrote of a ‘terrible intensity’ arising from the artists’ urgent need to convey their catastrophically changed reality, one capable of ‘drawing forth tormented sobbing and unexpected flashes of lightning’.

Réja’s ideas were further developed by Prinzhorn in what would become psychiatric art’s foundational text: Artistry of the Mentally Ill (1922). A psychiatrist at the Heidelberg Psychiatric Hospital, Prinzhorn expanded its existing collection to 6,000 paintings, drawings, manuscripts, collages and sculptures, seeing them as ‘not merely copies or memories of better days, but rather an expression of [the patients’] own experience of illness’. Prinzhorn possessed a deep artistic sensibility – having studied philosophy, art history and music – and the psychiatric art he curated formed part of his romantic self-mythology as a ‘man of the spirit and a nomadic outsider’. As Bettina Brand-Claussen, assistant curator of the Prinzhorn Collection in Heidelberg, noted in Beyond Reason: Art and Psychosis (1996): ‘He travelled around with a portfolio of art by mental [health] patients, and both he and it left a profound impression everywhere he went.’

Prinzhorn’s book highlighted the repeating ‘tendencies’ and ‘configurative process’ characterising his patients’ art; the complex symbolism they developed; and their compulsive need to fill whole sheets with scribbles ‘to the very edge as if a horror vacui gave the drawer no rest until every space was covered’. He introduced readers to 10 ‘schizophrenic masters’, devoting equal space and sensitivity to their art as to their tumultuous life histories. Of the ‘master’ August Klotz, whose watercolours teem with intricate patterns and benign grinning heads, he points out that Klotz hallucinated voices as he worked and ‘complained of seeing skulls everywhere’. Prinzhorn writes: ‘In his manic exaltation the patient scratches the wall.’ The patients’ anguish and delusions were essential to their process: the atelier in which their art was forged. As the researcher Allen S Weiss put it in 2000: ‘The work shows the limits of the formulation “symptom or art?” which, subsequent to Prinzhorn’s analysis must henceforth be posed as “symptom and art”.’

Prinzhorn’s 1922 book, and its ‘schizophrenic masters’, were warmly embraced by expressionists and surrealists, including Max Ernst and Paul Klee, who thought that psychiatric art incarnated a vital quest for authentic feeling and expression that had become suffocated by the alienating strictures of bourgeois life. (Critics later claimed their ‘discovery’ of patient art paralleled their mining of other sorts of alterity, including art from Africa, for elements of difference to appropriate.) When Germany came under Nazi rule, the risks of such essentialising became lethal. After Prinzhorn left the Heidelberg hospital, his successor was replaced by Carl Schneider, who viewed patient art as ‘pathological productions’. More than one ‘schizophrenic master’ was later euthanised when Schneider became scientific director of the Nazi mental patient extermination programme Aktion T4, while art from Prinzhorn’s collection was displayed alongside Jewish and expressionist art – all of it deemed the product of ‘sick minds’ – in the Nazi’s propagandist exhibition of ‘Degenerate Art’ in 1937.

Given this dark, freighted history, it’s hard to know how to view psychiatric art. Unlike a therapeutic byproduct, the work itself, not the process, is the point. Inge Jádi, a former director of the Prinzhorn collection, tells us how not to view such paintings: by gazing at them on a wall and admiring them on a purely aesthetic level – which is to miss their ‘inseparability from the artist’s existence as a whole’. Obscuring the context in which this work is created softens out of view a stark fact: this isn’t just art, but a supercharged act of meaning-making and resilience forged in the face of a consciousness-threatening existential crisis. ‘They are works of art almost by mistake,’ Jádi writes in 1996, ‘compulsively produced under imminent threat of extinction, as weapons to ward off death.’

This Idea was made possible through the support of a grant to Aeon+Psyche from the John Templeton Foundation. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Foundation. Funders to Aeon+Psyche are not involved in editorial decision-making.