A starry-eyed Romeo stares up at a balcony and sighs: ‘But, soft! what light through yonder window breaks? / It is the east, and Juliet is the sun.’

This utterance achieves several different effects. For one, it reveals to you something about Romeo’s inner mental life. You learn that he loves Juliet, and that he finds her beautiful. The expression is also likely to achieve certain imagistic effects. After hearing Romeo’s words, you may find yourself imagining Juliet as the sun, picturing her in a particular way. And, depending on how deep you want to go, you may find a dark intimation: while Juliet is warm and brilliant, prolonged exposure has its dangers – staring too long may leave one burned, even blinded.

This is a near-miraculous use of language. At its core, this metaphor is four simple words – ‘Juliet is the sun’ – that combine to make a patently false claim (Juliet, after all, is a human girl, not an astronomical object located 93 million miles away from Earth). Yet, despite both its simplicity and falsity, it achieves rich conversational effects.

It is not only a literary giant such as William Shakespeare who could pull off such a marvellous feat. Natural language is rife with metaphors. Most people produce them incessantly, and often with effects just as rich as Romeo’s. Imagine a friend calling you up and saying: ‘My relationship is a sinking ship.’ Though trite, you’ll learn that your friend’s relationship is in the process of failing. You’re also likely to picture your friend and their partner somewhere in the vicinity of an actual sinking ship. And you may find intimations that raise further questions for you: who is standing at the helm of this relationship – and who fled on a lifeboat at the first sign of taking on water?

Metaphor was once maligned by philosophers. Thomas Hobbes called metaphor an ‘abuse of speech’, and John Locke wrote that metaphors are ‘for nothing else but to insinuate wrong ideas, move the passions, and thereby mislead the judgment’ – the vilest of sins, for these 17th-century Enlightenment thinkers. But it is now recognised that metaphor is crucial to human communication, providing us with a method for extending the expressive power of literal speech. Indeed, we often find a metaphor so useful that it ‘dies’ and becomes literalised – ‘cappuccino’, ‘deadline’ and the phrase ‘can’t hold a candle to’ were all once novel metaphors. To put it metaphorically: today’s language is a graveyard strewn with the bones of yesterday’s metaphors.

How can speakers produce these vast arrays of effects by uttering a sentence that is usually false, and often patently absurd on the face of it? In other words, how does metaphor work?

This question has been the focus of a flourishing tradition since the 1950s which, at its best, draws together the fields of cognitive science, linguistics, and the philosophy of language (though philosophers as far back as Aristotle have been interested in metaphor).

We can distinguish between two different questions about how metaphors work their magic. First is the question of how a metaphorical message is derived from an utterance. It is simple to say how an utterance’s literal message is derived. Consider ‘Mars is red.’ If you know what ‘Mars’ means (it refers to a planet), and if you know what ‘is red’ means (it predicates a certain colour property), then it is easy to derive the literal message of ‘Mars is red’: you just stick together (compose) the meanings in the right way and, voilà, out pops the literal message.

With metaphorical speech, however, the message must be derived in a different way: we can’t simply associate the words of a metaphor with their conventional meanings and then compose those meanings as per usual – that would deliver the utterance’s literal message, not its metaphorical one. So how do we derive a metaphorical message from literal meanings?

Why does Romeo want us to compare Juliet and the sun?

Before we can answer this question, we’ll have to say something about another: namely, what capacities are required to ‘get’ a metaphor – in other words, which cognitive abilities are involved in the production and comprehension of metaphorical speech? One view is that the production and comprehension of metaphor requires speakers and hearers to employ ‘theory of mind’. This is not ‘theory of mind’ in any highfalutin sense. Insofar as you are someone who attributes mental states – eg, beliefs, desires, hopes and emotions – to others, you are (in the relevant sense) an expert practitioner of theory of mind.

We often employ theory of mind to explain the actions of others. Question: why did Jill go to the fridge? Answer: she wanted a beer (a desire) and thought she could find one in there (a belief). By attributing this belief-desire pair to Jill, we manage to explain why she acted in the way she did.

Now maybe something like this is going on with metaphor. Romeo utters ‘Juliet is the sun’. Question: why would he say such a thing? Answer: he wants you to compare Juliet and the sun (a desire), and thought that calling her the sun would get you to do that (a belief). A further question now arises: why does Romeo want us to compare Juliet and the sun? Well, perhaps (we might reason) he takes Juliet and the sun to be similar in certain respects, and he wants us to notice those similarities. And so on – there may be countless things we can figure out once we begin applying theory of mind.

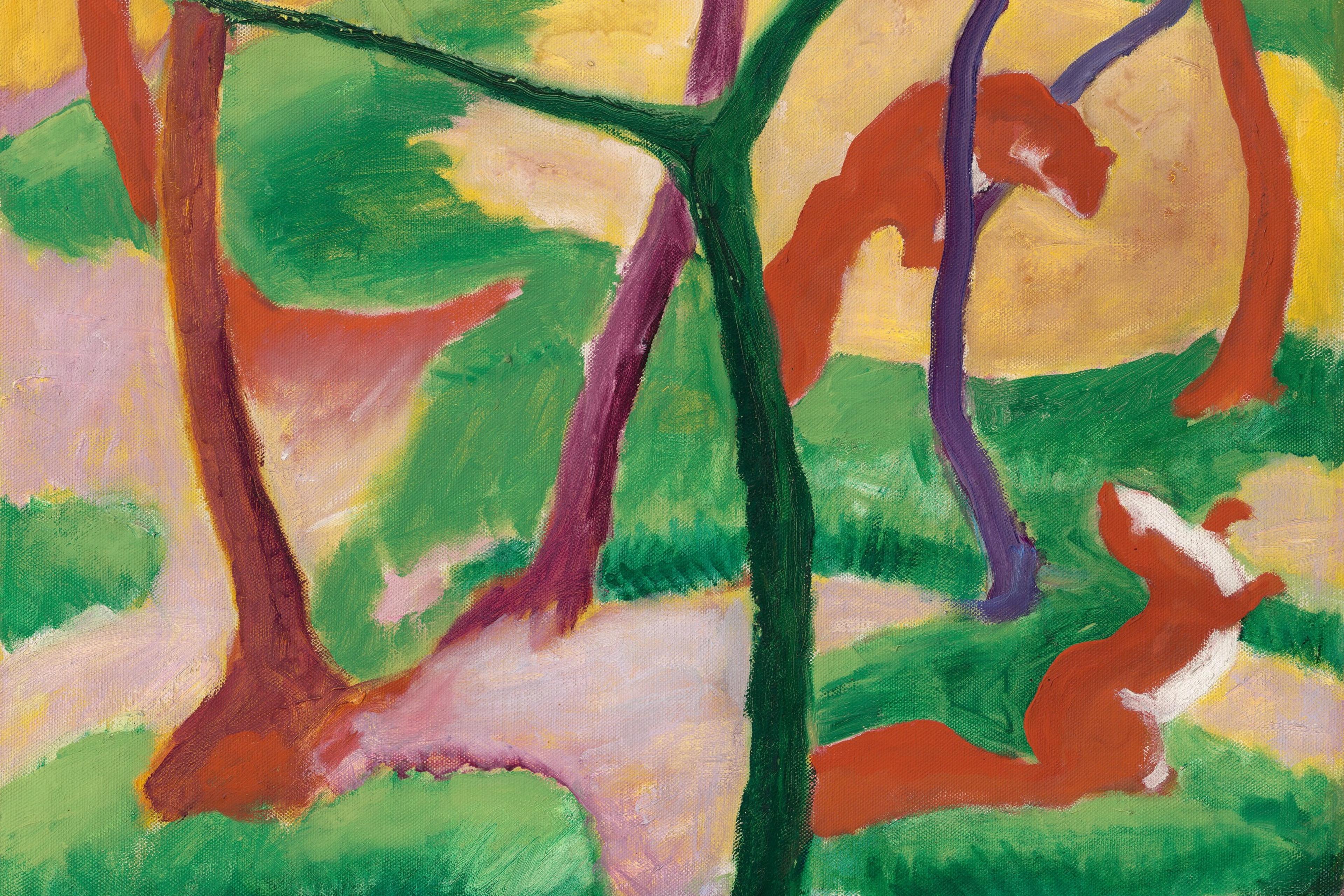

Naturally, there are further questions about the cognitive capacities that are employed in metaphor processing. It is clear, for instance, that metaphorical speech exploits some kind of analogical thinking or framing. When your friend tells you that her relationship is a sinking ship, she provides you with a kind of tool for thought: she is pointing out that one can frame her romantic relationship through – to put it metaphorically – the lens or perspective provided by the sinking of a ship. Or – to put it non-metaphorically – she points out that there exists a salient isomorphic mapping between the features of a sinking ship and her own failing relationship.

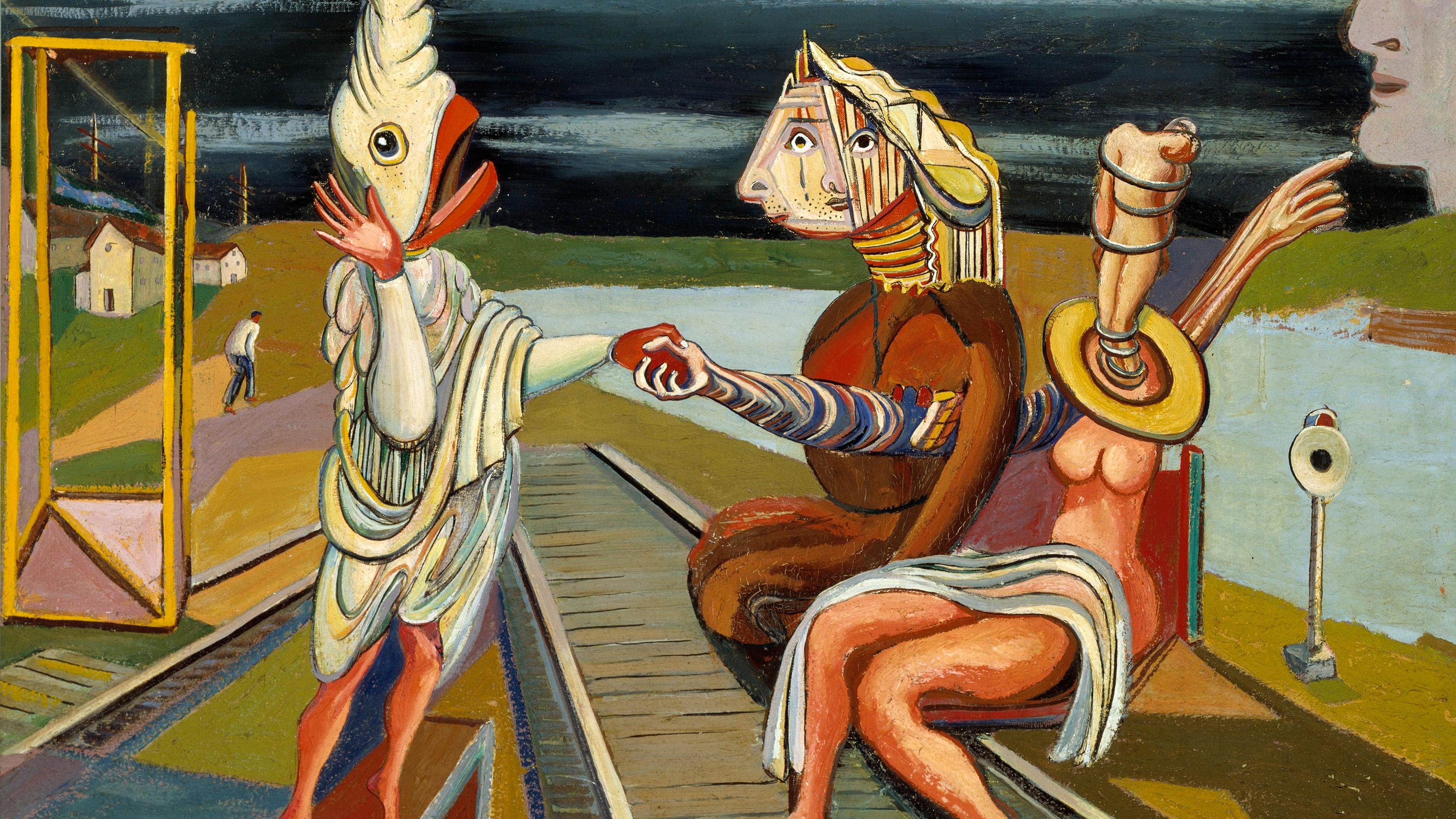

Theorists have also noted the importance of ‘seeing as’ when it comes to metaphor. Romeo, it is clear, sees Juliet as the sun – and by telling his audience that she is the sun, he is directing us to see Juliet as the sun, too (to imagine, make-believe or fancy her to be something that she is not). And in order to ‘get’ Romeo’s point, we may have to try out seeing Juliet as the sun ourselves – or to at least make an honest effort at doing so.

Returning to the first question of how a metaphor’s message is derived, one answer can be found in what we can call the ‘Gricean’ approach. H P Grice, in his ‘Logic and Conversation’ (1967), described explanatory resources that can enable theorists of communication to explain how the utterance of a sentence can be used to send a message other than the one that it literally encodes.

Consider the following example from Grice. You’re in charge of hiring a new school teacher, and you receive the following letter of recommendation for an applicant:

Dear Sir/Madam,

I can assure you that John has legible handwriting.

Best,

A Colleague

Wisely, you don’t hire John – the letter you received was absolutely damning. But why was that letter damning? After all, it didn’t actually say anything bad about John.

The reason you didn’t hire John is not what the letter said – it’s what it didn’t say. It’s easy to read between the lines: the writer, we assume, certainly would have extolled John’s qualifications if John had any. Since none were mentioned, John must not be qualified to be a teacher. And it’s understandable that the letter was written in this way, leaving its real message implicit – in general, we try to avoid saying negative things about our colleagues outright. Nonetheless, it’s easy to derive the intended message: don’t hire John!

Maybe metaphor works like that. When Romeo utters ‘Juliet is the sun’, we read between the lines and figure out his implicit message – that Juliet is beautiful – even though what Romeo says is just that Juliet is the (actual) sun. This would explain how we derive metaphorical messages that may differ radically from an utterance’s literal message.

Yet there is reason to doubt that a metaphor’s message is sent merely implicitly. Think back to John, the applicant with the damning letter of recommendation – and suppose that you disagree with the letter’s implicit message (that is, you think John is well qualified and, actually, should be offered the job). You might say: ‘Well, I don’t agree with what this letter is getting at,’ or perhaps: ‘Hey wait a second – John would be a great teacher.’ Both of these would successfully register your disagreement with the letter’s implicit message.

But could you register your disagreement by replying: ‘Actually, John doesn’t have legible handwriting’? The obvious answer is, I think, no – this would probably just be confusing since it would seem like you didn’t get what the letter-writer was really hinting at. In any case, it wouldn’t be a way of sending the message that John is a well-qualified candidate worthy of being hired.

Here’s the lesson I find in this: when a message is implicit in someone’s utterance, you can’t disagree with that implicit message just by negating the utterance. As we saw above, you have to find some other way of disagreeing with a merely implicit message (you have to say ‘I don’t agree with what you’re suggesting’ or whatever).

A metaphor’s message is not implicit in the words – rather, it is an explicit message

Let’s go back to the metaphor we started with: ‘Juliet is the sun’. Suppose that you and Romeo are long-time friends. Sadly, you’ve observed a pattern of toxic behaviour in his romantic life: Romeo becomes infatuated with a new girl every few weeks, comparing each one to some astronomical object or another before moving on to his next fling shortly thereafter. So when Romeo turns to you and says: ‘Juliet is the sun’, you’ve had enough. You reply: ‘No, Romeo, she isn’t the sun. She’s just some sexy tween, and you’ll be over her in a week!’ – a tough message, but a true one.

But wait! You disagreed with Romeo’s metaphorical message simply by negating his utterance – all you had to do was say that Juliet wasn’t the sun, and you thereby disagreed with the point Romeo was trying to make with the original metaphor. The lesson is that a metaphor’s message is not implicit in the words – rather, it is an explicit message. A metaphor imbues the very words of one’s utterance with new meanings – meanings that are there to be potentially negated by someone who disagrees with the metaphorical message carried by those words. The metaphorist somehow manages to induce a change in the meaning of the very words of their utterance.

How do we do this? How do we twist the literal meanings of words, and turn them into metaphorical meanings, when we deploy a successful metaphor? What clues must we give to our audiences in order to help them figure out our intended message? And how might the audience respond if they find the metaphor to be obscure or ambiguous, or if they find it to convey a distasteful perspective, or if they consider it inappropriate to speak metaphorically in that context?

We can make progress in the study of metaphor by contemplating these questions. The next time you come across a metaphor – I’m sure it won’t be long – try asking them. The answers may be keys that open a treasure chest of surprising depth – a chest filled with the flitting thoughts of our ancestors, captured and suspended in amber and stowed alongside other pearls of accreted meaning.