My dad had a bad death.

The lead-up was long – a decade-old stroke had forced an early retirement from carpentry – but the end was abrupt, avoidable. Shocking.

A night out drinking with friends like he’d done countless times before, but that his body, now 68 and sustained by blood thinners, could no longer handle. A slip getting into bed that caused a brain bleed, invisible and irrevocable by the time his roommate found him the next day.

My sister and I, both in the thick of COVID-19 bouts, needed special permission to enter the hospital. Decked in disposable gowns and cheek-chafing N95s, we held his hand and learned that recovery was out of the question. Consented to taking him off the vent. Arranged goodbyes with whoever could make it. And, in the final moments, curled across pairs of chairs pushed together beside him until his familiar snores gave way to silence.

The months that followed were a fog of knockout grief and messy estate logistics, the combination of which sent me sinking to the floor most days.

A year and a half later, the fog has lifted considerably, but one thing that remains is the spectre of self-blame. I know I’m not directly responsible, nor was I even privy to the precipitating events – but therein lies the problem. I left so many signs unheeded, plans half-laid.

The last time I saw my dad, we were touring senior living apartments I’d convinced him to consider after a family member approached me with concerns about his current setup. I’d lurched into ungainly action, scheduling visits at every well-reviewed complex within 10 miles of his best friend’s house, where he ate dinner every Sunday. But the prospects were grim. Long, dim hallways gave way to square-box units. Every resident we passed was at least 15 years his elder, yet nothing was designed to accommodate his cane and heavy limp.

It was a spectacular misfire. I let the ensuing sorrow and frustration fester into unmade visits and undialled phone calls until we hadn’t spoken for the three weeks preceding his death. I behaved imperfectly. And I failed to save him.

If I’d found better housing options, I thought to myself, maybe he’d be too busy settling into his new digs to attend a rowdy holiday party. If I’d bothered to call him even once in those intervening weeks, maybe he wouldn’t have felt quite so alone and decided to self-medicate. If I’d been firmer in my response the last time he’d fallen after drinking too much (at my wedding, seven months earlier), maybe he’d have quit altogether.

Ruminating on what might have been – entertaining the ‘if onlys’ and ‘woulda, coulda, shouldas’ that bubble up in grief – is normal, and can at times be adaptive. But for those of us who feel like we’re crumpling under the burden, it can be useful to challenge the ‘what ifs’ when they surface. ‘Yeah, it would have been different if we had done something different,’ says Litsa Williams, a therapist and co-founder of the What’s Your Grief community. But most of the time, ‘we have no idea how it would have been different. It may have been different and they still died.’

The kind of self-blame and self-questioning I have experienced may be especially common among loved ones of the deceased in the wake of so-called ‘bad’ deaths – like my dad’s. The criteria are subjective, but peaceful, painless, old-age deaths are often seen as ‘good’, while those involving violence, isolation, pain or some other such suffering are labelled ‘bad’. But the ‘good’ deaths are ‘very few and far between in my experience’, Williams notes. And the reality is rarely so binary for those left behind; death, she says, is ‘always complicated’.

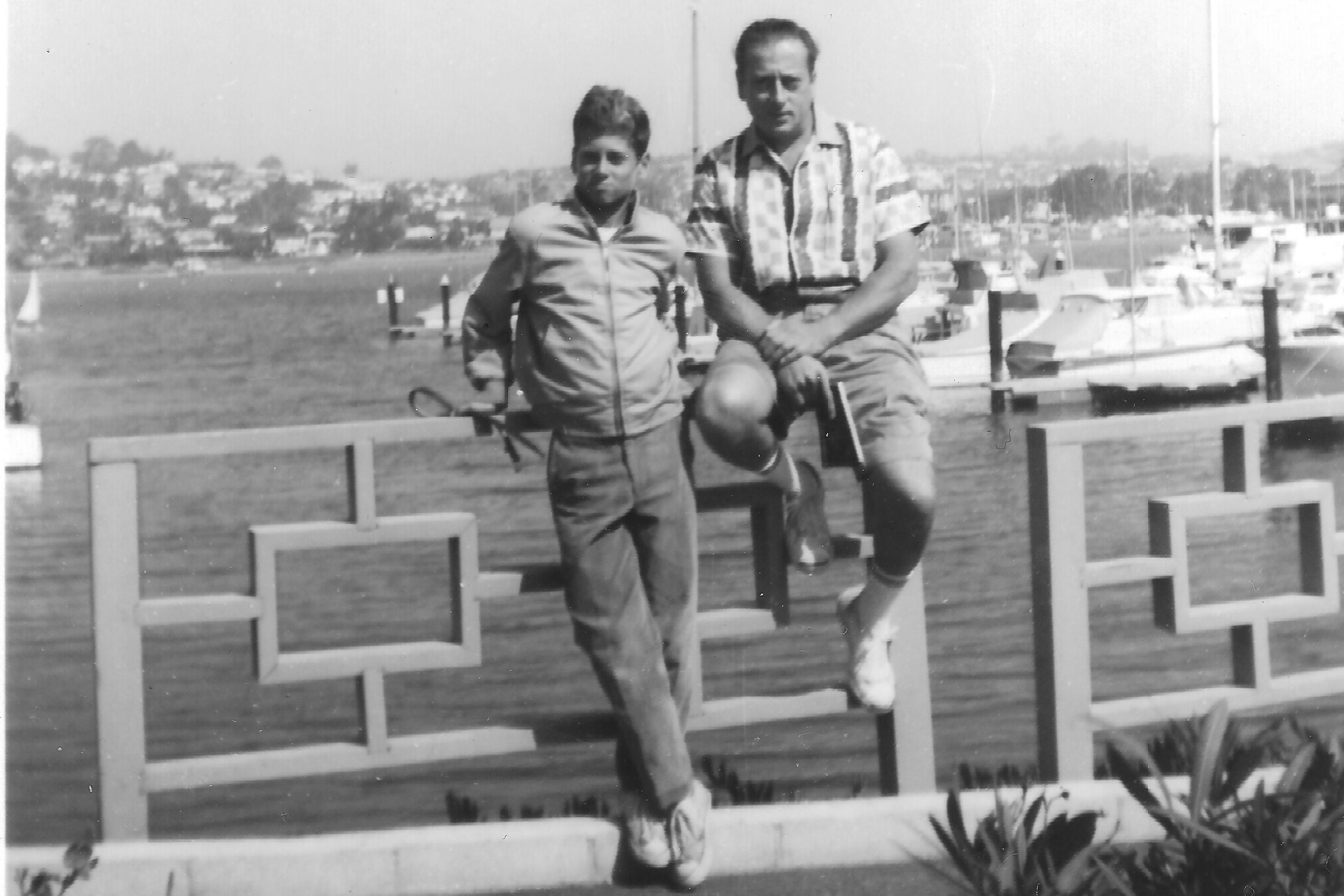

The author and her father on her wedding day. Photo by Twilight Photo Video

My relationship with my dad was complicated, which made my grief more complicated, too. As I grew up, he stayed a big kid, one who was emotionally ill-equipped to help me navigate life’s complexities. Some of these started young: parental divorce, illness and unprocessed trauma that muddied the waters of who should be taking care of whom. By the time I was 30, and he really needed my help transitioning to his next home, I was already exhausted from shouldering so much unspoken responsibility for so long.

Despite this fatigue, the resentments and resignation, I loved my dad so much, in ways it seems I’d forgotten until everything came rushing back in the days after his death. Visceral, breath-catching love capped the swells of my grief like so much seafoam, crushing my chest, salt-stinging my insides. Memories from childhood, long suppressed, came roaring back: sword fights with sticks of salami in the grocery store; off-key harmonising to Al Green and Tracy Chapman on cassette; drives around the neighbourhood in his pickup truck to kill time between dinner and dance class, surveying all the houses he’d built along the way. After he died, his best qualities were recast as urgent guideposts for how to be without him. Kind. Creative. Loyal. Goofy. Open-hearted.

‘I still haven’t found an emotional and full-body experience that is even close to being similar to grief,’ says Sherman Lee, an associate professor of psychology at Christopher Newport University in Virginia. ‘A lot of people feel like they’re losing their minds.’ For me, that experience included the wrenching-open of the floodgates of love, mixed with the pain of self-blame.

In grief contexts, these responses can signal a yearning for control

This is not at all uncommon, according to the clinical psychologist Robert Neimeyer, director of the Portland Institute for Loss and Transition. In a study that he and Lee conducted as part of their work on The Pandemic Grief Project, they found that, among more than 200 adult mourners who had lost a loved one to COVID-19, a majority reported some form of self-blame. A quick death catches us off guard. ‘When it occurs suddenly, and we have no chance to negotiate an extended end-of-life period with someone, then we know that the incidence of unfinished business’ – the sense of something left unsaid or unresolved – ‘is higher, and it tends to trouble us more profoundly,’ Neimeyer explains.

Like some other seemingly adverse processes, however, self-blame might serve a function for many bereaved people. Common shades of it include regret (‘I wish I’d done something differently’), guilt (‘I did something bad’), and shame (‘I am bad’). In grief contexts, these responses can signal a yearning for control, Williams says. Something that I’ve personally done many times, both before my dad’s death and since then, is turn inward to self-flagellate, attempting to ‘fix’ the one thing still in my grasp – myself – when everything around me has spun into chaos. Taking the blame can feel as if you have wrested back a modicum of control, even comfort, in ‘this world where [you] have to be a person who now knows that the worst things can happen,’ Williams explains.

Sometimes, self-blame is also a means to forge a ‘continuing bond’. This is the psychological term for the impulse that so many of us have to keep the relationship with our deceased alive. It’s why, for example, my sister and I held birthday and death-anniversary celebrations for my dad.

‘Some of my clients, they told me that they don’t want me to alleviate their guilt feeling,’ says Jie Li, a counsellor and associate professor of psychology at Renmin University of China, who has studied this timbre of grief in Chinese mourners. To those clients, the feelings of guilt mean ‘we’re far from over, and as long as this guilt exists in my mind, I feel close to you.’ That’s because guilt is an interpersonal emotion – it’s addressed from one person toward another and so, in grief, it can embody the mourner’s enduring connection to their departed loved one.

But filtering a relationship through unexamined guilt often comes at ‘a huge cost’, Li says, such as more intense or prolonged psychological distress. It’s worth seeking a more adaptive path forward.

Healing, for some, can include letting go of the need for a sense of control, or giving up on trying to make guilt go away completely, and instead developing the ‘muscle to carry it’, says Joanne Cacciatore, a professor and senior global futures scholar at Arizona State University.

To start the strength training, bereaved people, perhaps with the help of a grief counsellor or therapist, can make the radical decision to validate what Neimeyer calls the ‘grain of truth’ in our guilt. To accept those unmade visits or undialled calls, without judgment, and imagine what it would look like to be worthy of love, forgiveness and compassion anyway. ‘Life is not simply black or white, good or bad. I am not either responsible or irresponsible,’ Neimeyer says. So it’s helpful to ‘recognise that paradox and ambivalence pervade every moment. Every relationship. Every event.’ Including the death of a loved one.

Such an acknowledgement counters the silence and silencing around feelings of guilt. These feelings can otherwise calcify into shame for grievers, Cacciatore says, especially because admissions of guilt are so often met with platitudes and dismissals (‘Oh honey, you can’t blame yourself’) rather than genuine consideration.

Getting past what Cacciatore calls the ‘collective cultural avoidance’ of self-blame requires us to think – and narrate – more expansively. ‘We’re looking at building a story that is sufficiently whole and complex, that has room even to hold the nasty bits. But without those dominating the story,’ Neimeyer says. ‘And this gives us freedom to be less than perfect as well.’

The muck of self-blame, hosed down and shined up, is love, too

This practice is as exhilarating as it is wrenching, and one that I’ve been nurturing in my daily encounters with grief. For fleeting moments, I’m able to hold the heaviness of my dad’s role in his death alongside all the ways I could have better shown up for him. Instead of being the victim or the villain, we both get to be whole people. We both get grace, and we both get to grow.

My reflections have been inspired by a technique that Neimeyer showed me – a guided conversation in which I play both parts. With Neimeyer’s direction, I imagined telling my dad that I feel responsible for his death and apologising for all the ways I failed him. Then, I ‘heard’ his response, the words springing more readily to mind than my own: ‘You worry too much, kiddo. I’m proud of you, and I love you. Stay safe.’ The sentiments are spare and trite and achingly him.

‘The pain that you’re experiencing,’ Neimeyer says, is ‘in relationship to a father who still exists in your mind. And it’s with that father you’re needing to come to a different [place].’ What’s more, he says: ‘You can have access to the dad you’ve always needed. And in a kind of beautiful and redemptive way, you can give him the chance to be that.’

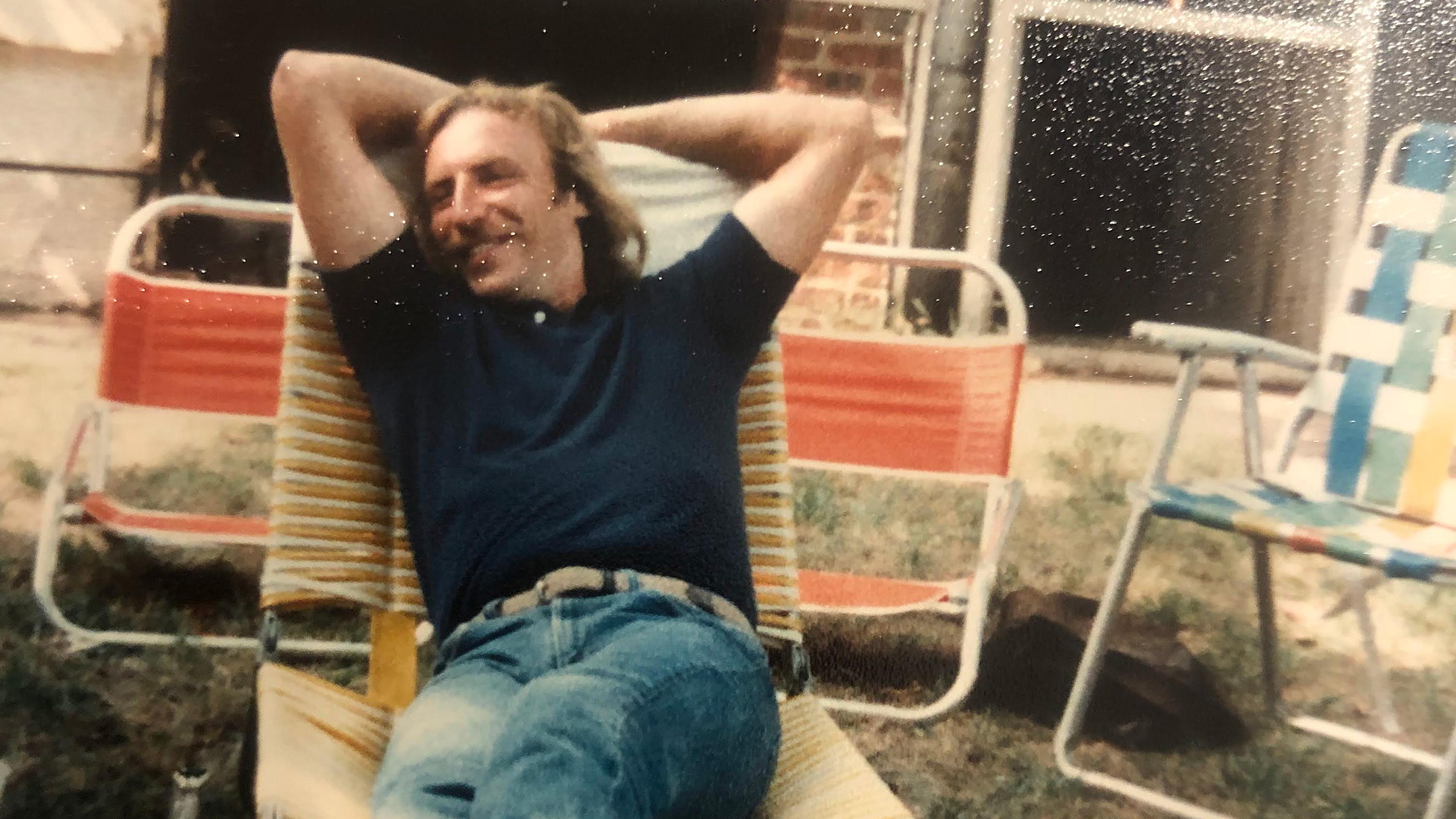

When my therapist asked me what grief feels like, a few weeks after my dad’s death, I answered without hesitation: ‘It feels like love.’ The muck of self-blame, hosed down and shined up, is love, too. Deep love for a man who is gone, but ever present. He’s there in my desire to build narrative arcs the way he built living room archways; in every FedEx truck I’ve seen since he told me the white space between the logo’s ‘E’ and ‘x’ forms an arrow; in all the off-colour stories his lifelong friends-turned-pallbearers shared around his gravestone on his 69th birthday – stories of roughhousing with nail guns, and cutting middle school to buy cigarettes, and hard-partying on roof beams, and countless other bad decisions that could have killed him sooner.

I loved hearing those stories, as imperfect as they were. This article is my addition. A tribute to a father, imperfect and yet so loved, from his daughter, just as imperfect and perhaps just as lovable.