Søren Kierkegaard, the lyrical Danish philosopher, was keenly observant of the ways in which people ordered their lives. Like an existentialist Socrates, Kierkegaard prodded his readers with questions that nurtured earnestness and self-reflection. Expressed in various terms and styles, one such prod provokes surprising self-assessment: how should we relate ourselves to moral exemplars?

Of course, most of us know to avoid the behaviour of the brigade of golems that march through history. But what about those beacons of goodness?

Take, for example, Angelina Grimké, the youngest child of a fabulously rich South Carolinian plantation owner who in the late 1820s stood up one evening from the dining room table, vehemently denounced slavery, and proceeded to go north to become a lifelong abolitionist. Or take Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the German pastor who returned from the United States to Germany in 1939 to join in the plot against Hitler, only to be caught and executed a few months before the war’s end. Finally, what do we make of the late congressman and civil rights warrior John Lewis who, after being arrested and beaten scores of times, was nearly bludgeoned to death in March 1965 as he led a march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama? Are these moral exemplars cut from different cloth than the rest of us? Is it enough to shake our heads in admiration of these martyrs for the good?

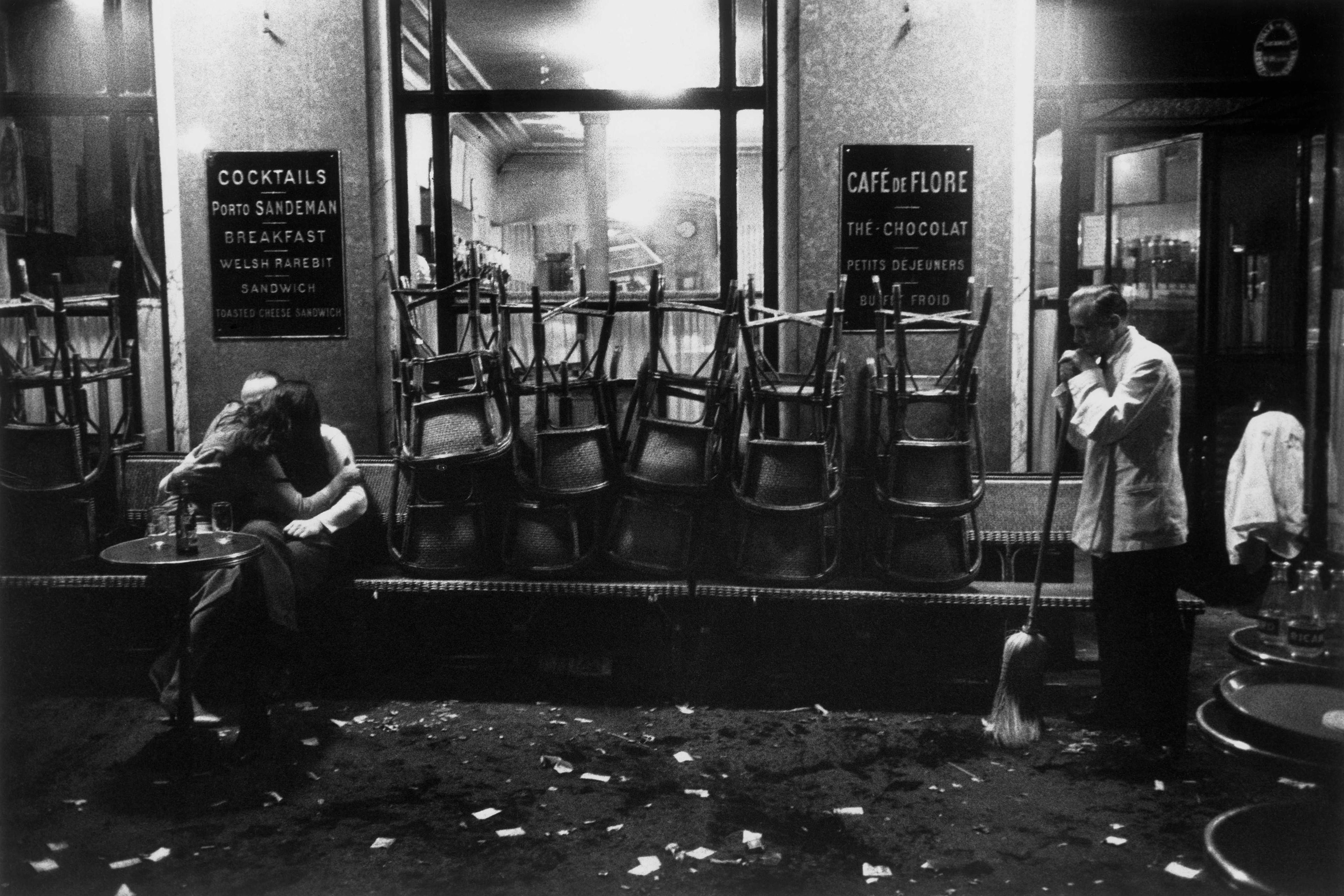

John Lewis (light coat, centre) under attack from a state trooper on the march from Selma to Montgomery on 7 March 1965. Photo by Bettmann/Getty

Kierkegaard, who once wrote that his purpose in writing was to make life more difficult for his readers, recognised that resentment or envy is a common reaction to ethical exemplars. Addressing this venomous pairing, Kierkegaard refers to the words of Heraclitus:

The Ephesians would do well to hang themselves, every grown man of them, and leave the city to beardless lads; for they have cast out Hermodorus, the best man among them, saying: ‘We will have none who is best among us; if there be any such, let him be so elsewhere and among others.’

It is, as Friedrich Nietzsche would put it in 1878, all too human for us semirational bipeds to denigrate individuals whose brave deeds spark envy and make us ashamed to look in the mirror. Kierkegaard, who fancied himself an expert on the green emotion, writes:

Envy is secret admiration. An admirer who feels that he cannot become happy by abandoning himself to it chooses to be envious of that which he admires.

The same author did not, however, find much to admire in admiration itself. Writing under the pseudonym Johannes Climacus, Kierkegaard drew an equivalence between the universal and the ethical, and in so doing hammered out an important distinction:

That one person can swim the channel, and a second person knows 24 languages, and a third person walks on his hands etc – one can admire that si placet [if you please]. But if the person presented is supposed to be great with regard to the universal because of his virtue, his faith, his nobility, his faithfulness, his perseverance, etc, then admiration is a deceptive relation … What is great with regard to the universal must therefore not be presented as an object for admiration, but as a requirement.

Admiration for Kierkegaard is a carpet path to the easy chair. He reminds us: ‘there is an infinite difference between an admirer and an imitator, because an imitator is, or at least strives to be what he admires.’ Admiration alone is akin to being content to hit ‘Like’ on Facebook when I read about someone offering their spare room to a homeless man. Instead, admiration should instruct me to stop worrying about the crabgrass in my lawn and do something for people with no roofs over their heads.

Like Immanuel Kant, Kierkegaard believed that a knowledge of right and wrong is universally distributed. Since we do not need more knowledge or skills of analysis to be decent human beings, Kierkegaard would have vehemently opposed the burgeoning ethics expert industry. His contribution to ethics was to reveal our ethical evasions, that is, the ways in which we pull the wool over our own eyes by talking ourselves out of inconvenient moral truths. In a note to himself, Kierkegaard scribbles:

Aesthetically … admiration is the highest … Then along comes the ethical and says: as a matter of fact, wanting to imitate is decisive; admiration has no place or is an evasion.

Admiration that does not lead to action is one of the moral off-ramps Kierkegaard tries to dissuade us from taking.

On my reckoning, Kierkegaard detected a poisonous assumption lurking behind the admiration impulse – that is, the assumption that some people are born moral geniuses and the rest of us just don’t have the right stuff to do the right thing when it propels us in the wrong direction from happiness. The individual who is willing to stop at admiration seems to conceive of morality as akin to an artistic, intellectual or athletic talent. Treating moral character as a talent, I can look in the rearview mirror and tell myself that my neighbour, who was one of the Freedom Riders protesting segregated buses at a time when all I could think of was playing college football, was just born with more moral muscle than me.

‘Upbuilding’ is not a word that drips off tongues or keyboards much today but, more than any other goal, Kierkegaard intended his writings to be upbuilding for his readers, among whom he numbered himself. He was emphatic in his upbuilding reminder that, rich or poor, educated or not, we all have it in us to be loving, kind and merciful human beings, as explained in Works of Love (1847); yes, even the downtrodden and marginalised are contained within the margin of this requirement.

There was a time when I was about to divorce myself from my Danish sage for this kind of demand, and Kierkegaard’s seeming indifference to the material circumstances of life. My irritation came to a boil when I gleaned a passage in Works of Love. There, Kierkegaard, the born-into-wealth author, recommended that the one thing the poor can do when they see the rich going to a feast is to refrain from making the fat cats feel guilty! ‘Easy for Magister Kierkegaard to say,’ I sneered. Later, however, I was talked out of my cancelling inclinations by the Kierkegaard scholar M Jamie Ferreira, who interpreted this paragraph as Kierkegaard fixing the point that no one is too powerless or poor to be merciful.

Aristotle, no less than those committed to nurture in the ‘nature vs nurture’ debate, might observe that those who grow up in less than nurturing hardscrabble circumstances are likely to find it especially taxing to put the care of others over their own interests. Likewise, my experience as a limo driver has taught me that the very well-to-do generally have a hard time grasping that they are not the centre of the world. Depth psychologist that he was, Kierkegaard recognised that each of us is burdened with different inner impediments but one common obstacle is the temptation to think it enough to admire the good Samaritan while ignoring the requirement to strive to become one. If there is anything admirable about admiration, it is its ability to reveal what we take to be good and, though easier said than done, impel us to action.