When Chris lost all our money, we were in our early 60s and kid No 1 was finishing her third year of college. Worried that we didn’t have enough to see us through retirement, Chris had invested in a company whose mission was to recruit smart people stuck in dead-end jobs and train them to be programmers. Once trained, the ex-cashiers, ex-waiters and ex-Uber drivers landed well-paying tech careers that catapulted them into the middle class, such as it is. In the company’s early years, its brilliant founder and early investors did fantastically well by doing good. Ten years on, the initial investments had returned 15 times their original value and the venture had expanded from one city to eight. Ever the optimist, Chris was convinced that profits could only keep rising, at least until the untapped talents of a dozen more cities had realised the American dream and we’d put kid No 2 through college.

‘Don’t invest more than you can afford to lose,’ was my sage advice.

‘It’s a real company,’ Chris replied. ‘Worst case, it won’t grow much. It’s not going to go poof.’

But the future is a mystery. One day, the company’s brilliant founder decided to run for public office. In what now seems like a quaint ethical gesture from a more principled era, he sold his controlling shares to a private equity firm whose commitment to raising the downtrodden proved desultory. Meanwhile, COVID-19 was making it hard to place trainees, and offshore competition was undercutting their fees. Chris remained sanguine through it all. But then came the triumph of AI, which rendered the company’s newly minted programmers obsolete, and kicked the legs out from under its business model.

On our wedding anniversary last April, we took the day off, and that’s when Chris told me everything. Hiking on an overcast Wednesday with no one else around, we unleashed the dog so she could vault over downed trees and chase deer. In recent years, when the recovery of his investment seemed delayed rather than hopeless, Chris had borrowed heavily from our home equity line of credit, so not only had he lost the college money, but he’d accumulated so much debt that another loan was impossible. Up till then, Chris had refused to admit how bad it was. Picking our way across streambeds, one sentence following another, each footfall sinking deeper into the mud, I learned the extent of the disaster.

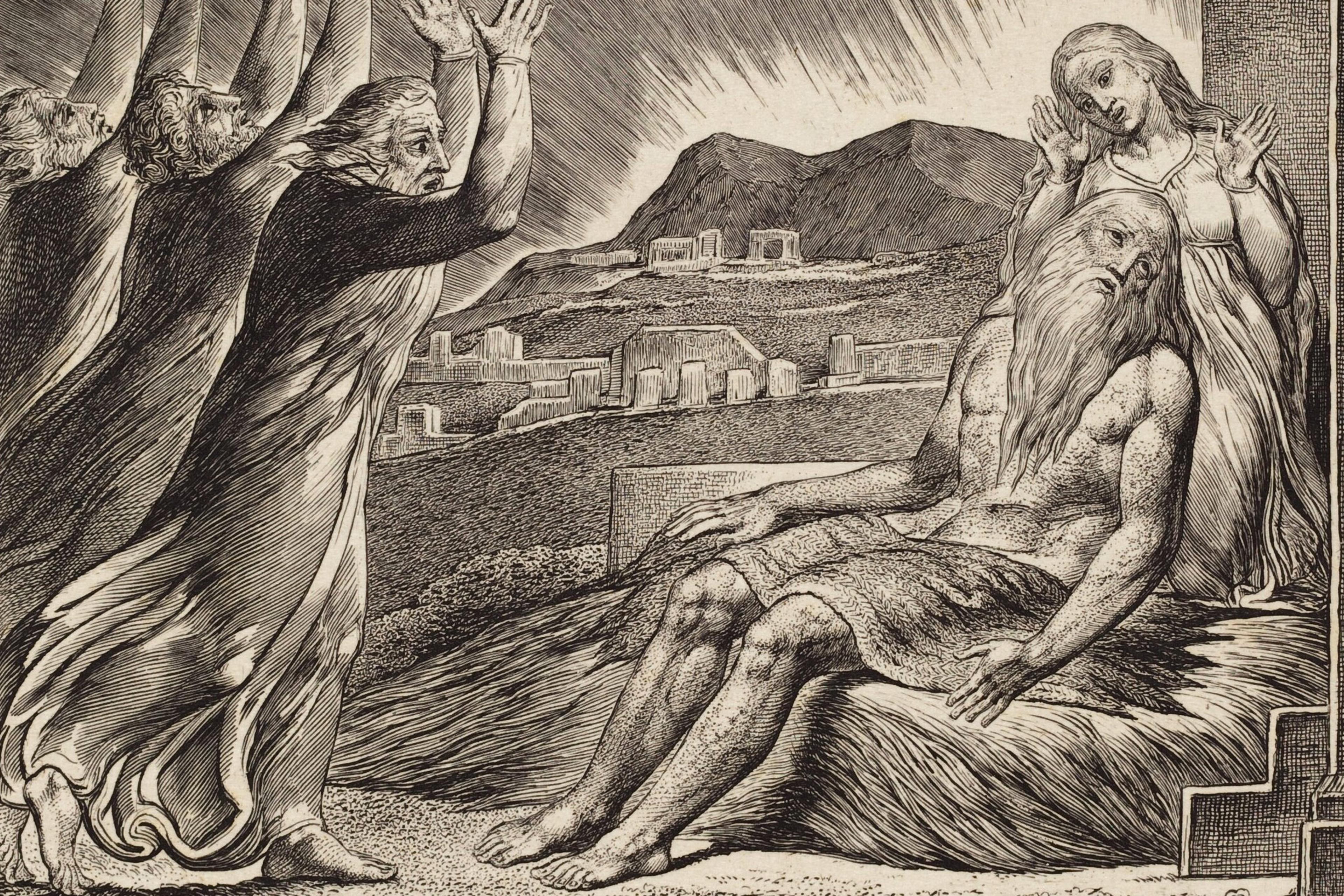

My friend Diana stated the obvious: ‘What part of diversification did he not understand?’ I met Diana when we were both studying mathematics in college. She was clobbered by multiple sclerosis during graduate school, and for the past 10 years has lived in a nursing home outside Tel Aviv, nearly bedridden. We Zoom every couple of weeks, and she offered to send us a book that helped her once, on the topic of losing everything, so at least we would know we’re not alone.

In one sense, we have been alone. Our parents, Chris’s and mine, have been gone for decades. My dad was the last to go. His heart gave out on our daughter’s first birthday, so the kids never knew their grandparents. It’s a financial liability, not to have grandparents. The kids’ friends all have at least one. People marry young here, so some of our kids’ friends’ parents even have grandparents of their own. Grandparents can help with tuition, and when they die there’s something to inherit – maybe insurance, often a house. Chris and I had no such windfalls in the wings.

When at last Chris finished talking, I said something I’d never dared think, much less say, in the 40 years we’d been together: ‘No Jew would ever have done this.’ He said that wasn’t true, there are plenty of poor Jews. But they don’t get poor like this, I thought. I’ve never known a Jewish optimist.

What is optimism anyway but a failure of judgment? Do you really believe you can outrun the dogs? Fifty generations riding the turbulent currents of history from one end of Europe to the other had inscribed the message in my genes that fate is not to be trusted. Anyone who believes otherwise is a fool. This was clear enough to my parents, two accountants whose own parents had narrowly escaped history’s terrible course, and for whom nothing was more sacred than ensuring their children’s future. And that prompted an even more unsettling thought. In all our years together, I’d never doubted Chris’s intelligence. But was I missing something? Had I married a fool? And what did that make me?

He could drive at speeds just this side of terror, knowing no hazards lurked around the bend

Over our many years together, Chris and I had rarely argued about money but, when we did, it was usually about one thing: he is generous beyond reason. We live in a tough town, or maybe it’s just tough times all around. Either way, a lot of the friends we’ve made here – artists, single mothers, a recovering addict who was like an uncle to our children – have been hard pressed. Chris’s business kept us more secure than most. So he’s never turned down a request for a loan, which is to say a gift. In this respect, Chris is what some people might call an angel. But in all those years, he never put anything aside for his own family in a truly secure place where nothing could reach it. In his mind, there would always be more coming in. That was optimism.

And yet. Let’s be honest. It was Chris’s optimism that drew me to him in the first place. Chris wasn’t raised among people who ate dinner with their shoes on and a suitcase by the door. His ancestors braved the Oregon Trail, reached their promised land, and then flourished for six generations. By the time Chris arrived on the scene, their continued good fortune seemed guaranteed. In Chris’s world, he could drive at speeds just this side of terror, knowing no hazards lurked around the bend. His confidence charmed and reassured me.

And while it might make him a bit foolish, that generous heart of his is good for more than a loan. He’s quick to forgive, and who doesn’t need forgiveness every now and then? Chris believes that everything will be better tomorrow, even me.

Even without money in the bank, and buried in debt, life continues the same as before. Chris spends most days parked in a chair in front of three computer screens, running the same little tech business that he started 35 years ago. Around 11 am, he walks to Starbucks with the dog. At 4.30 pm, he takes the dog to an open field where neighbours gather for a doggie playdate. He gets his socialising there with the dogs and then comes home and shares the local gossip with me. One of us picks up the boy from high school, we all have dinner together, and Chris returns upstairs to his office.

I work downstairs in the dining room, writing technical reports on biomedical research or climate change. Most of my reports are funded by the federal government, so you can guess how much work I’m getting these days. When I don’t have an assignment, I scrounge for material to turn into a story, like the poor Jew who turns his ratty old coat into a jacket, then a vest, a scarf, a button and, finally, a song. Like this.

Had I taken a real job with benefits, I’d have been able to keep saving for my children’s future

And I know that, while the bad investment was Chris’s idea, I’m also to blame. In the early years of our marriage, I was a bench scientist, until I was hired as a professor at a small local university. I enjoyed teaching and threw myself into my classes, but I wasn’t as successful at publishing research papers, which are the currency of academia. After being denied tenure when our daughter was an infant, I chose to become a freelance writer, opting for lower pay in exchange for the freedom to spend more time with my child. Chris’s income had always dwarfed mine and, after I left the university, we all grew to depend on him more.

That was a mistake. Had I taken a real job with benefits, I’d have been able to keep saving for my children’s future, as my own parents had saved for mine. Chris might lose his share, but mine would be safe.

What do we do now? For the foreseeable future, we’ll both keep working. One way or another, we’ll get the boy through college. Chris recently hired some new employees, visionary and talented, and he thinks they’ll bring in bigger clients with more work. Perhaps they will.

And if we can’t keep up with the loan – if we lose our house? Then we’ll find some way to adapt. My ancestors may not have been favoured by history, but neither did they surrender to it. More times than I can possibly know, they picked up with nothing and moved on. I would not exist otherwise. Chris and I may be getting up there in years, but we’re not dead yet.

The last day of Passover this year was on Sunday, so I went to synagogue for the Yizkor service, when you pray for the deceased. I was the youngest cousin from a large extended family, which has left me with a multitude of dead relatives. As my mind began to focus on aunts and uncles long gone, I suddenly recalled that the previous night I had dreamed of my mother. She looked young and lovely, dressed in her most stylish purple wool suit and heels, with her dyed-blonde hair freshly coiffed and a faint whiff of Chloé. It made me so happy to have seen my mother like that, before Alzheimer’s ravaged her. She was at her most beautiful in that dream, and as the rabbi chanted El Malei Rachamim, the prayer for the dead, I felt closer to her than I had in a very long time.

An hour later, as I was walking out of the synagogue, all of a sudden I remembered why, in my dream, I’d been so happy to see my mother looking healthy and beautiful. I thought she’d have money.