Warning: this film features rapidly flashing images that can be distressing to photosensitive viewers.

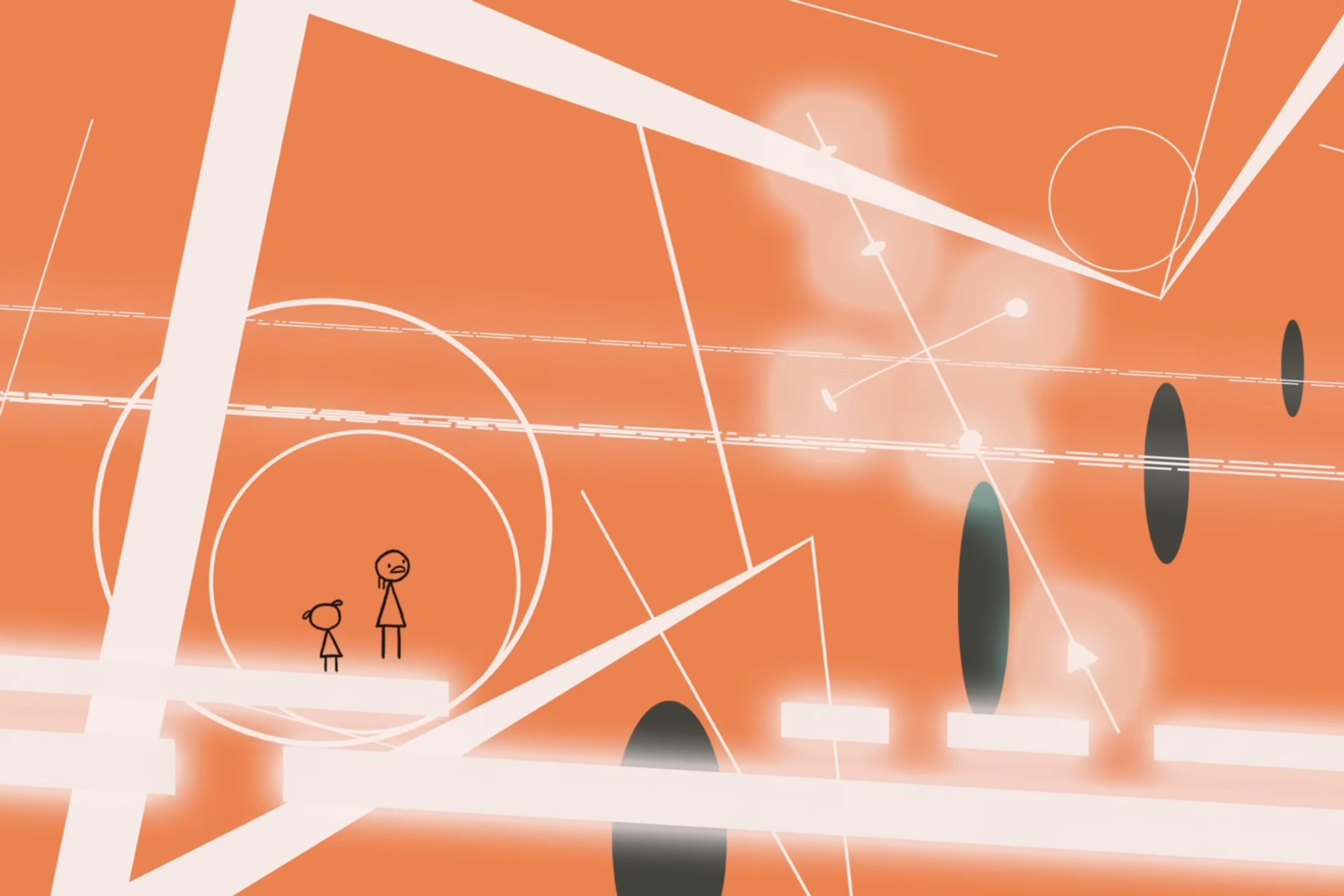

It’s a lot to ask of a short film that it take you somewhere you’ve never been in just a few minutes. It’s even more to ask that this experience of newness spans both visuals and ideas. Yet the German artist Patrick Buhr does just that with his short film From Over Here (2020). Through a distinctive animation style that combines a sparse colour palette of blue, black and white, and shaky stick figures moving in and out of three dimensions, Buhr immerses viewers in a peculiar world that, unless you’re already familiar with his work, probably doesn’t resemble any digital space you’ve ever encountered. Letters on screen, often a shortcut in animation, are deployed here with care and creativity, dotting the landscape, shuffling in and out of meaning, and lending the piece a handcrafted aesthetic. But beyond just impressive world-building for its own sake, Buhr’s trippy terrain is constructed as a venue for examining his relationship with stuttering (or stammering) and himself.

Buhr begins by addressing the audience directly, letting them know that, while all viewers are welcome, the next nine minutes are aimed at a ‘small group of people’ who might describe themselves, like him, as ‘translingual’. The film concludes with a whirlwind animated sequence dedicated to his fellow stutterers in which the characters he’s introduced are engulfed in swarms of letters. In between, several of these characters serve as metaphors for different experiences of stuttering, which those without the speech interruption might struggle to understand. Through this bookending device, Buhr gently toys with the concept of in-groups and out-groups, placing people with a less typical experience of speech at the centre, and most viewers on the outside and along for the ride.

A more direct exploration of stuttering unfolds when Buhr unpackages a bit of his own story, from what he calls ‘stutter boy’ to ‘speed reciting art student’. He describes an art film he once started and never quite finished, in which he declaimed Goethe’s Faust (1790) at breakneck pace in front of a camera, employing a skill he learned as a means of overcoming his own stutter. He looks back at his failed attempt with more than a hint of self-deprecation, referring to himself as ‘trying to show off what he learned in his free time, which apparently he has too much of’. He then zooms out to the present moment, wondering if he’s once again engaged in a trivial bit of filmmaking – or something deeper. A skittish original score based on Caprice No 24 by Niccolò Paganini helps to frame Buhr’s self-interrogations as lighthearted rather than brooding.

If that sounds like a lot, it is. It’s an experimental work that, on a visceral level, can be enjoyed for its playful rhythms and heady visuals in one watch, but might take two or more viewings to fully appreciate. It’s about stuttering, yes – a tribute to those who, in Buhr’s words, may feel as though they were born ‘next to’ spoken language, rather than ‘into it’. But buried in the film’s layers is a complex reflection on navigating artistry. Buhr weaves between meta-analysis and non-linear storytelling in a way that seems to comment not only on his relationship with articulation as a speaker, but also as an artist. Perhaps a credit to his evolution since his art school days, Buhr’s experimentation builds a world that’s peculiar and challenging but also engaging enough that you might revisit it as much for its charms as for its intricacies.

Written by Adam D’Arpino