It is often said that contemporary Western societies are in the grip of an excessive and irrational fear of death, a thanatophobia. For instance, this is the diagnosis given by the grief counsellor and author Stephen Jenkinson who observes that:

[P]eople in any culture inherit their understandings of dying much more than they create them. In our case, that inheritance takes the form of an extraordinary degree of aversion to and dread of dying. My phrase for it was that the culture is incontrovertibly and, for the most part, unconsciously death-phobic.

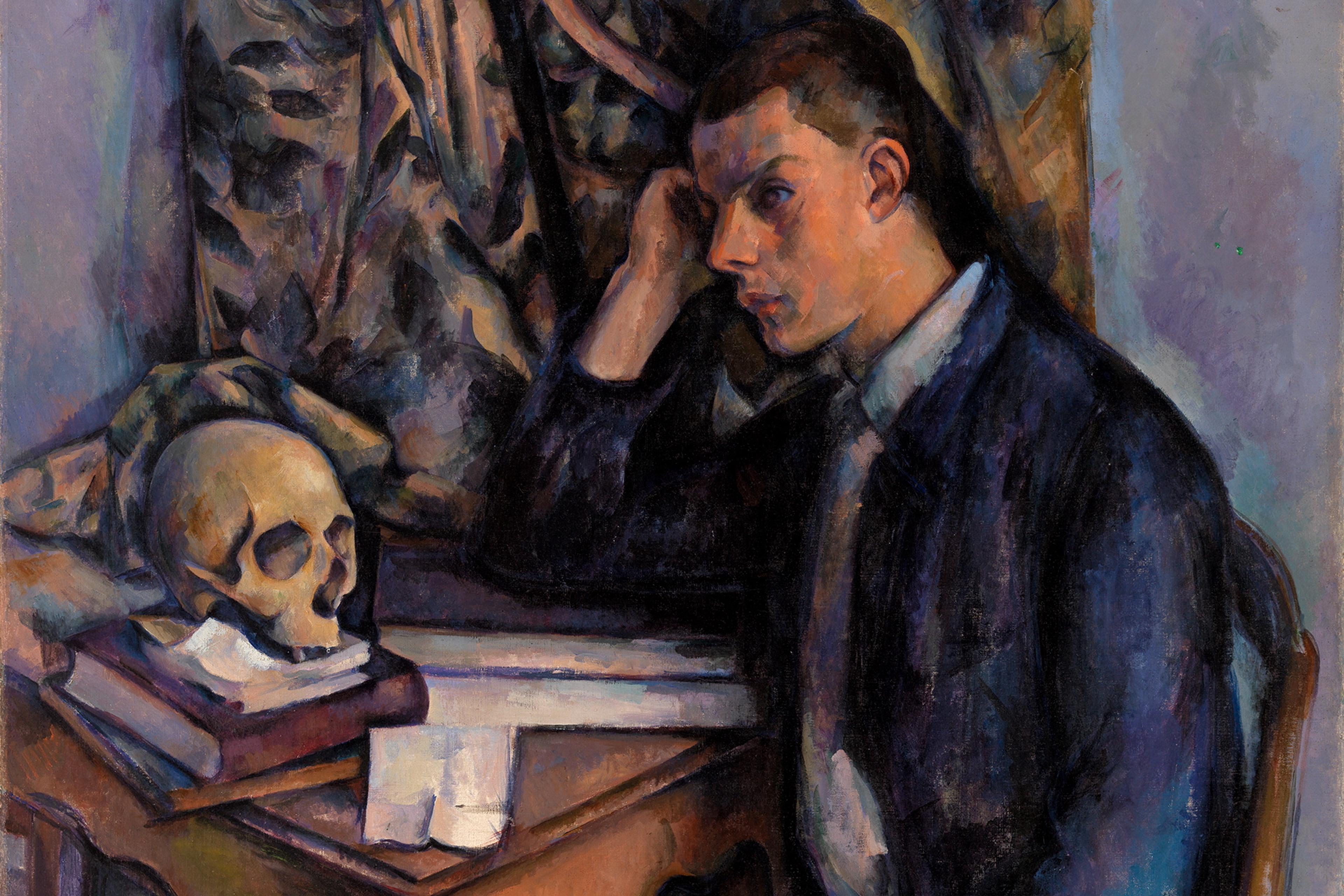

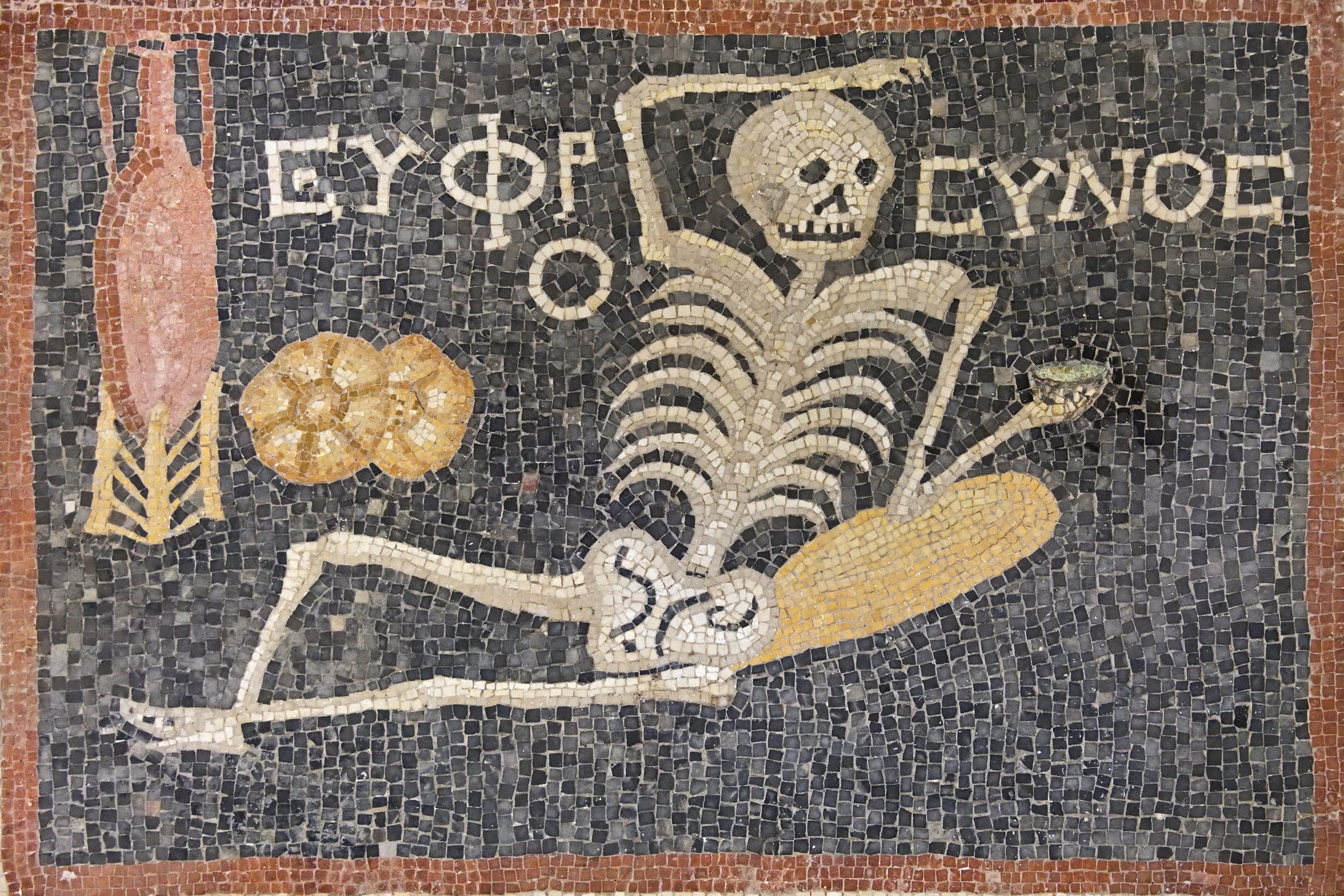

Jenkinson’s diagnosis aligns with that of the French historian Philippe Ariès, the author of a seminal study of the history of Western attitudes to death. Ariès argues that whereas our premodern ancestors maintained an equanimous relation to death, we moderns suffer a ‘horror of death’, which he describes as a ‘violent attachment to the things of life … a passion for being, an anxiety at not sufficiently being.’

Evidence for this view is not hard to come by. We are surrounded by advertisements for various supplements and ointments that promise to restore our youth or hide every sign that it is fleeting (and that we are going to die). Billionaires such as Jeff Bezos and corporations such as Google are spending billions on anti-ageing research. Popular science books such as Transcend: Nine Steps to Living Well Forever (2009) by Raymond Kurzweil and Terry Grossman, Lifespan: Why We Age – and Why We Don’t Have To (2019) by David Sinclair, and Ageless: The New Science of Getting Older Without Getting Old (2020) by Andrew Steele have become bestsellers. The spirituality genre similarly assures us that we can keep on living, albeit in a different realm. The much-publicised multimillionaire Bryan Johnson, who spends $2 million per year on a personal anti-ageing regimen (the Blueprint), is building a community under the banner ‘Don’t Die’. Our collective fear of death is also evidenced by how we die: outside society’s view, in a hospital bed, drugged and connected to machines via intravenous tubes, fighting death until our last breath. Those around us ensure that everything is done to keep us alive.

The standard view that contemporary culture is distinctly thanatophobic certainly isn’t groundless. Nevertheless, I think it can be shown to be a myth.

Ten years or so ago, I attended a small dinner party in Brooklyn. The topic of getting older came up, and Susan, one of the guests, volunteered that she thought it was wonderful to age, that it would be so boring to stay young, and that she hoped to live no longer than to 80. As someone who has always hated the fleeting nature of our physical prime and the brevity of life, I was flabbergasted. This set me on an intellectual journey that culminated in my book The Case Against Death (2022).

While writing it, I taught a course on death at New York University, and the first day of every class I surveyed the students’ attitudes toward death and longevity. When I asked how long they wanted to live in good health, the average response was about 85 years. Only two or three students in each class expressed interest in living beyond 120 years, which is commonly recognised as the natural lifespan limit. Most said they wanted to live long enough to have grandchildren and then die a painless death surrounded by their loved ones. Even those who wished to live beyond the natural lifespan held this belief in a relaxed, intellectual manner. It wasn’t so much that they feared death; rather, they thought that ‘it could be fun to live longer’. There was no sense of urgency or any feeling that it was important for them not to die. They were mostly as complacent as Susan.

Only 32 per cent of Americans report being ‘afraid or very afraid’ of dying

‘Sure, but they were all young,’ you may object. True, but the wider public shares their attitude. In 2013, the Pew Research Center asked a representative sample of Americans how long they would like to live, and more than two-thirds said their ideal lifespan was between 78 and 100 years. Only 4 per cent of participants said they wanted to live beyond 120. When asked whether they would want a safe treatment that would slow ageing (and hence keep them in robust health) and enable them to live to at least 120, only a minority – 38 per cent – answered yes. These results are extremely surprising given the assumption that modern culture is beset by an extreme fear of death. After all, anyone truly afraid of death should be expected to want to avoid it for as long as possible.

According to the most recent annual survey by Chapman University in California of what Americans fear most, only 32 per cent of participants report being ‘afraid or very afraid’ of dying. This places dying 51st on their list of the 90 most common fears, behind fears of AI taking over their jobs, government snooping, heights, and sharks.

What about the contemporary practice of sequestering the dying, and medically extending life – any kind of life – for as long as possible? This isn’t necessarily indicative of an excessive fear of death. It is a consequence of the expanding resources of medicine applied in accordance with the traditional ethical principle of providing the best care to the patient, regardless of age. It doesn’t reflect a greater fear of death than in the past, but rather the fact we have better tools to resist it. One reason that the struggle sometimes continues beyond the point of futility is that it is hard to know when to give up. Doctors can also give up too early. My aunt was told that there was not much they could do for her husband, my uncle, but that was almost 15 years ago, and he is in quite good health at this moment. They tried to comfort her by saying: ‘You have to realise he is old,’ even though he was barely 70 at the time.

The dominant societal ethos is that quality of life is more important than quantity of life

The point about how we make dying ‘invisible’ by relegating it to hospitals has a fairly straightforward explanation: dying is less public because modern society is more specialised. No one would make the analogous argument that the fact that women give birth in hospitals or that we place our children in daycare is best explained by reference to paedophobia.

The dominant societal ethos is not ‘life at any cost’, but rather that quality of life is more important than quantity of life. In another Pew Research Center survey in 2013, this one on attitudes toward end-of-life care, only 31 per cent of participants said that medical staff should always do everything possible to save a patient. When asked about their personal end-of-life preferences, 52 per cent said that they would want their doctor to stop treatment and let them die if they had an incurable disease that made them totally dependent on another for care. In 2024, more active euthanasia is also viewed as morally acceptable: a recent Gallup poll found that 71 per cent of Americans believe that doctors should be ‘allowed by law to end the patient’s life by some painless means if the patient and his or her family request it’. Assisted dying is legal in nine European countries, in Canada, and in 10 US states, with indications that this may expand to more jurisdictions. These laws, along with the number of people who receive assisted dying and the public’s attitudes toward end-of-life care, reveal that values such as healthy functioning, independence and freedom from suffering are often considered more important than simply avoiding death.

We are so accustomed to the narrative that ours is a thanatophobic society that we often see only confirming evidence. Take the ready acceptance of the ubiquitous story of ‘billionaires who want to become immortal’ and how it reflects our collective fear of death. In reality, of the approximately 3,000 billionaires in the world, only about 30 invest in anti-ageing science, with only one – the German tech billionaire Michael Greve – investing more than a tiny fraction of his fortune. The longevity biotech firm Altos Labs made headlines when it launched with a $3 billion initial commitment. Many reacted to how large the initial commitment was – and it certainly was large for a ‘start-up’, indeed, the largest ever – but, on the other hand, everything is relative. Bezos, who on a good day is worth more than $220 billion, is rumoured to be one of the investors and, relative to his fortune, it’s not a large commitment. For comparison, he spent around $500 million building Koru, his 417-foot yacht. This is how much he cares about immortality. A society truly obsessed with avoiding death would have headlines denouncing billionaires like Bezos for not doing more to solve ageing and extend life. As it is, he has received more criticism for his investment in Altos Labs than for splurging on his ostentatious sailboat. In the political sphere, solving ageing and radically increasing life expectancy is not even on the agenda.

Personally, I rarely experience fear of death. I have felt it on occasions, but most of the time more immediate worries occupy my bandwidth. In this regard, I am typical of my culture, if my argument is correct. However, contrary to many and, in particular, many philosophers, I do consider death eminently worthy of fear. If death is the permanent end, then dying is one of the worst things that can happen to a person. There is no point in wallowing in fear, but we should fear it enough to want to do what can be done to avoid it. This is analogous to how we should fear other dangers, such as climate change and nuclear war. Just as I wish that there were more done to mitigate these threats, I wish that more was done to promote science with the potential to enable us to live to 120 and perhaps indefinitely. There are different ways we can explain the lack of fear: we have more immediate things to worry about; we are distracted; we are unable to imagine ourselves dead (as Sigmund Freud thought); we are invested in the imaginary immortality of legacy or in religion. Much of philosophy, religion, psychology and other cultural expressions aim at overcoming our fear of death. Perhaps one could say that we have been too successful in this undertaking. In an era of new scientific possibilities, our complacency appears to prevent us from doing what we can to save our lives.

The case against the taken-for-granted notion that our culture is thanatophobic is, I think, surprisingly strong. I propose a counter narrative: mainstream attitudes to death in modern Western societies and most other modern societies around the world are death complacent. We think that quality of life is more important than quantity of life – healthspan over lifespan – and we see fear of death as something to overcome. Even an enemy of death such as Bryan Johnson insists that he does not fear death: ‘I know what fear feels like, and I don’t experience that emotion when contemplating death.’ For him, the desire to prolong life is a value judgment, not an expression of fear; it is an expression of his ‘passion for being’ rather than his ‘horror of death’, in Ariès’s words. When comparing Johnson’s lack of fear with the supposed fearlessness of strongly religious premodern societies, there is an important difference: unlike Johnson, they did not think that death was the permanent end of a person. They denied the reality of death. I venture that contemporary societies have a greater proportion than ever before of people who both accept that death means personal annihilation, yet remain largely unafraid of it.