The first time I tried to breathe underwater, it almost didn’t work. I was beginning my first descent in open water – scuba-diving parlance for sinking, on purpose, into the sea. I was with a guide and another beginning diver, and as we drifted downward, each of my frenzied inhales was accompanied by a burst of bath-warm water. Growing up, I had been worshipful and wary of the ocean’s vastness, the way it went on forever. How was it possible, then, that every inch of that expanse was here, now, pressing in on me? My legs tingled as they dangled into emptiness. Silt and sand, stirred up by recent unusually heavy rains, clouded my vision, and my ribs seemed to constrict around my lungs.

You are fine, I told myself, blinking hard and swallowing more salt from Savusavu Bay. If you stop the dive, everyone will be mad at you.

Another few feet down, and I could admit that enduring other people’s anger was better than drowning. I jerked my thumbs upward, scuba for ascend, and we rose back to the surface. ‘I think there’s something wrong,’ I told Tua, our guide, breathlessly. ‘There’s water coming into my regulator.’

He examined the mouthpiece that provided my air during the dive, and I treaded water and prepared to be told to relax. That breathing a bit of water was normal. That I would just have to get used to it.

‘You’re right, it’s ripped,’ he said, smiling like believing me was a simple, obvious, easy thing. Tua had been diving for long enough – first for fun, then with the determination of an aspiring divemaster, and now as a lead guide at a resort named for a scuba pioneer – that it took him only moments to replace the rubber mouthpiece that had been letting water mix wantonly with my supply of precious air. We began our descent anew, this time with Tua holding my hand. It was a kindness, based on the reasonable assumption that, after my equipment issue, I might be scared.

And I am scared, of a lot of things. I’m scared of the ocean even though I adore it, even though I grew up swimming in it every summer. I am scared of the inside of my own mind, though I grew up swimming in that, too. A lifetime of watching my mom endure chronic illness without the resources to receive compassionate healthcare has left me scared of being unable to communicate, of being isolated, of being injured beyond repair. I am scared of the dark. And, most embarrassingly, I’m often scared to sleep, especially alone.

I’ve never been able to sleep well. In one grainy home video, my father is holding me and cradling my head. I’m over a year old, plenty mature enough to manage my own neck but refusing anyway. Probably because I’m tired. ‘She hates to sleep,’ my dad says to the assorted family members nodding sympathetically throughout the frame. ‘She just fights it and fights it.’

More than two decades later, there’s something reassuring about the video. Some part of me – the part that puts my phone in the kitchen at night, and barring that uses my phone to watch soothing videos, and barring that says fuck it and doomscrolls while a Benadryl works its way into my bloodstream – takes comfort in knowing I’ve always been like this. That part can also admit it has gotten worse over time, even as I have learned to support my own skull. It’s not that I’m afraid of something specific, so much as that the vulnerability of sleep invites a sinister infinity of possibilities. When I’m alone in the dark, my mind reminds me that anything, something terrifying, could happen.

The darkness around me seemed to ripple with life, inky and aware and out to get me

Entirely by accident, diving immersed me in that fear. I never expected to scuba dive, so I didn’t know to be afraid of it until it was already happening.

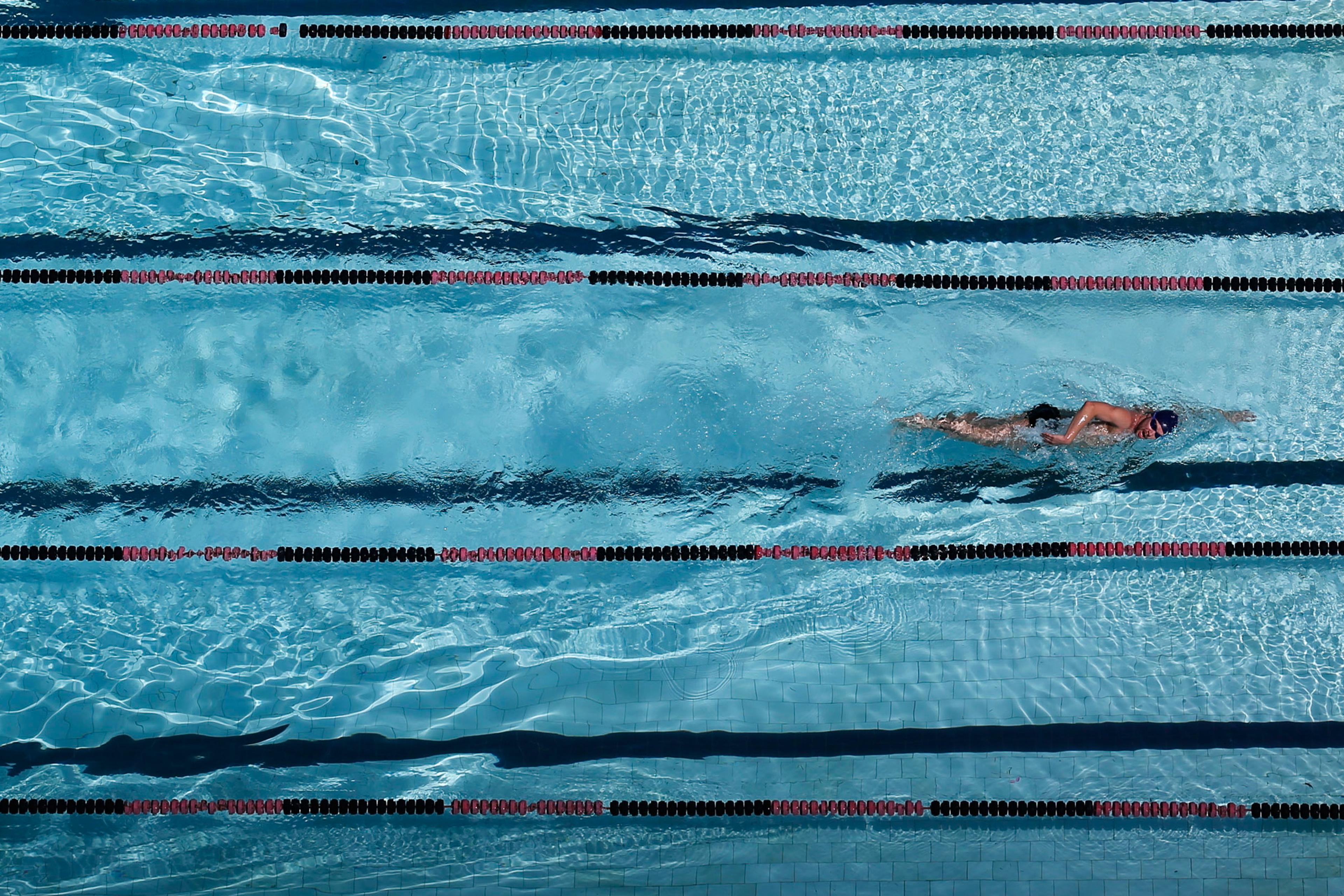

But before I could dive in the ocean, I had to practise in a pool. It was heated, busy, and a few blocks from Times Square. There I met Karen, who explored shipwrecks and teaches aspiring divers as a way of letting off steam from her job conducting medical research for investment firms. Karen told me to put my head underwater and take my mask off, one of the basic skills required to get your PADI Open Water Diver certification. I tried to comply, and wept. My fear was expansive and impressive – the kind I felt when I lay in bed at night and the darkness around me seemed to ripple with life, inky and aware and out to get me.

Karen, kind and efficient, tried to have me descend alongside her to the bottom of the pool, but I felt the water pressure constricting my chest and thought of freak aneurysms, heart attacks, nitrogen bubbles slipping insidiously through my bloodstream. Karen added an extra day to my training to compensate for the meltdowns I had before and after each skill level, and I eked out the progress needed for stage one of my certification.

Which brought me to stage two, in the ocean off the shore of Fiji. Forty feet of water filtered the reds and yellows out of the world and cloaked everything in shades of shifting blue.

I let go of Tua’s hand all on my own.

Almost everyone who has post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) also has trouble sleeping. And, according to at least three therapists – including the one I immediately quit seeing in sophomore year of college after she delivered the initial diagnosis (sorry, Urania) – I have PTSD. Specifically, I have C-PTSD, or complex post-traumatic stress disorder, which results from extended, repeated trauma as opposed to an isolated event.

Whether it’s a violent home environment, systemic discrimination and cruelty, or the malicious tangle of a healthcare system that gleefully profits while the sick slowly suffer, it’s not good for children to see their caretakers brutalised. Especially when that brutality is ignored or accepted.

It wasn’t good for me to see my mom suffer – neither the most memorable hospitalisations and injuries, nor the small, constant indignities. It was something about the repetition, stretching out interminably in front of us even as it pressed ever closer in the years before her death. It was something about treading water, being told to relax and get used to it.

I’d spent the time leading up to my first ocean dive terrified that I’d be unable to discern a real problem through the murk of my free-floating fear, and certain that, if I did encounter one, I’d be unable to communicate it. If I was being honest with myself, I’d been nursing some version of this concern much longer than just the lead-up to the dive. And then, my heart hammering and my every breath bringing salt water along with air, my fear had come to pass.

It’s something about the pressure, which emulates a weighted blanket or a womb

But I’d asked for help and been listened to, believed, offered a solution. Now in the ocean, I felt the water pressure like an embrace. Coral spiralled below and towered above us, an unlikely architecture of branches and fans tended by tiny fish. My fear dissipated skyward with the bubbles of each exhale. That night, alone in a bed almost 8,000 miles from home, I slept soundly.

Maybe it shouldn’t have been so simple. Maybe, it was. There’s not a lot of research into the relationship between trauma and diving, but what does exist suggests the benefits go beyond what I’d initially assumed: that people who can afford regular diving trips can also afford really good trauma therapy. Some organisations of military veterans and disabled divers swear by it, as does a therapist and neuroscience PhD candidate I spoke with once, who says diving saved her life. It’s something about the pressure, which emulates a weighted blanket or a womb. It’s something about the relative sensory deprivation of immersion, which has been documented by studies focused on reduced environmental stimulation therapy to ease anxiety and depression. It’s something about the health benefits of nature and the unparalleled awe it incites.

The day after my first dive, Tua informed us there would be a night dive that evening. It was scheduled for another member of our group who needed it to secure an advanced certification, but we were all welcome to join if we wanted, which of course I didn’t. I may have unexpectedly overcome my fears by day, but I was still the same person who’d lain in bed countless times barely breathing, feeling menaced by lightlessness. I didn’t want to be at the bottom of the ocean at night.

Yet I heard myself say yes. The sun set and we descended with it, this time holding flashlights. This descent was more chaotic, our flashlight beams swinging haphazardly and illuminating sand and tiny organisms swirling in the water around us but not much else as we made our way to the seafloor and settled on our knees. I tried hard not to think about the miles of dark water, pressing in on us from all sides.

And then I let myself think about them anyway. Something terrifying could happen, my brain dutifully reminded me. Tua gestured for us to turn off our flashlights. Without giving myself time to fully understand, I did.

There was nothing. And then there were motes of yellow-green, illuminating the shape of Tua’s hand as it waved back and forth through the water and ignited bioluminescent plankton. Something terrifying is already happening, I answered myself, pushing my hands through the water as well and watching as they, too, were gilded with light and life. And it’s incredible. It’s something about immersion in yourself, the purest form of exposure therapy. It’s something about asking for and receiving help. It’s something about kneeling on the ocean floor surrounded by rippling, interminable darkness, save for the bioluminescence sparking from your waving hands.