Why do our growing environmental and political crises, bearing existential risk for human beings, trigger irrational spending and consumption? I call it asteroid economics. We consume with abandon because we sense destruction. Why save for a future when we might not exist? Why conserve if the planet is dying? Whether it’s climate collapse, nuclear war or cyber-triggered Armageddon, the figurative asteroid is coming, so we might as well spend now.

So-called doom spending – a phenomenon where people spend money to cope with stress – presents an unsettling paradox: reports meant to inspire caution instead trigger abandon, self-indulgence. People aren’t ignoring the dangers of climate change, nuclear weapons or artificial intelligence threats; they’re shopping their way through them.

Throughout history, societies facing existential threats have not responded with conservation but with spectacular abandon. During the French financial crisis of the 1780s, aristocrats facing fiscal collapse reflexively intensified luxury consumption rather than investing in reform or refortification of the military. As thousands of workers protested outside the Palace of Versailles in 1786, courtiers reportedly enjoyed opulent balls. During the Black Death, survivors spent wildly rather than saving. Italian people ‘gave themselves up to the enjoyment of worldly riches’ with banquets and unbridled luxury, while England’s King Edward III held tournaments where all were encouraged to maintain festive spirits, believing parsimony was pointless when death resided in every street.

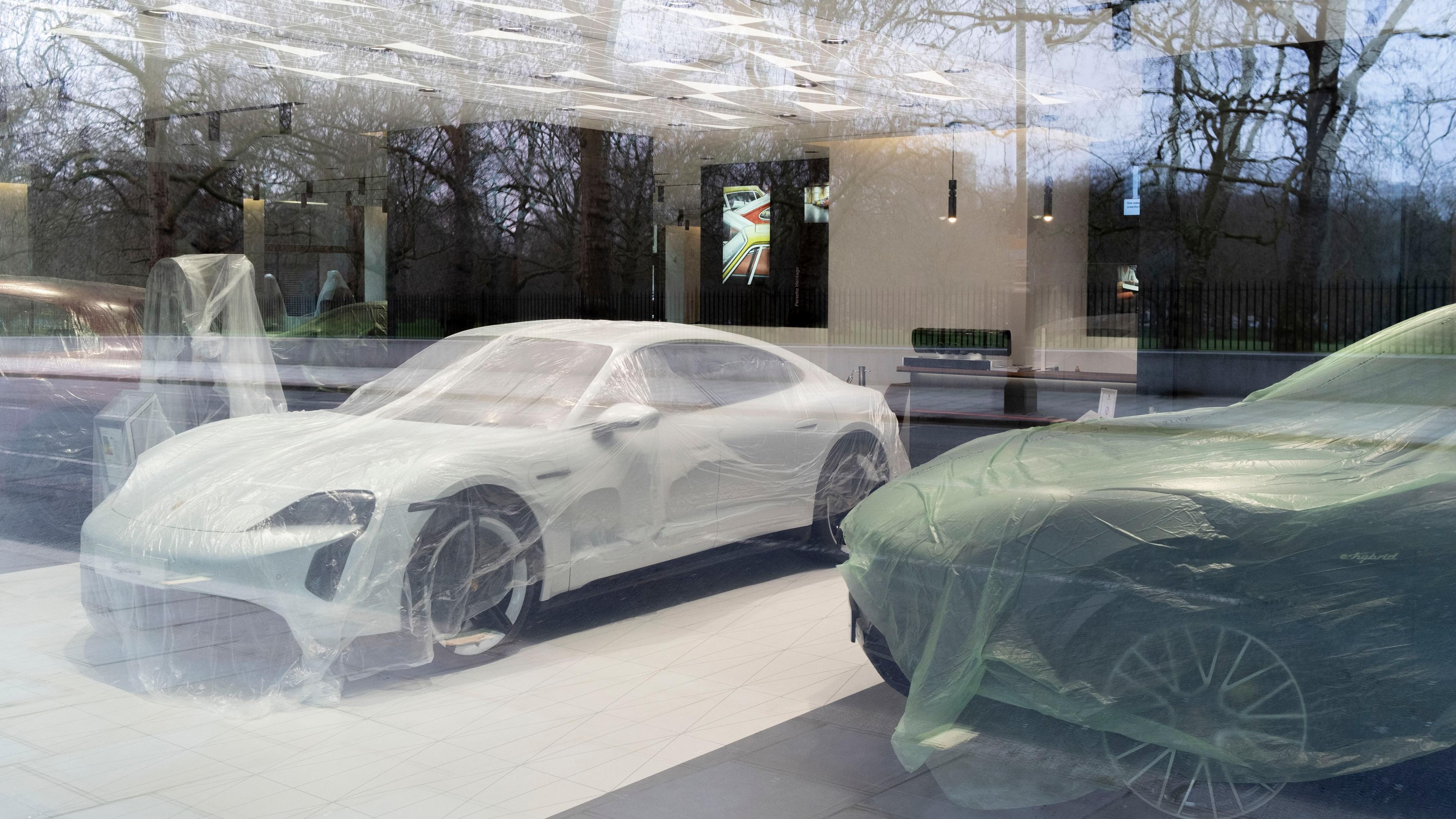

The COVID-19 pandemic provides the clearest modern-day example of this response to existential threat. As economies collapsed, luxury car purchases surged inexplicably. Some Mercedes industry dealers reported being ‘genuinely surprised’ by unexpected demand surges in mid-2020, and the sales of ultra-luxury brands like Ferrari, Lamborghini and Rolls-Royce were growing during the crisis. In 2024, the World Economic Forum (WEF) issued a report on escalating environmental, political and technological challenges that threaten civilisation itself. The WEF report didn’t emerge in isolation. The United Nations issued an inaugural risk report, while polling showed people worldwide were increasingly worried about existential threats.

The convergence seems almost synchronistic, several institutions worldwide independently acknowledging the precarious state we’ve created for ourselves. Within a year of these reports, auto sales surged to record levels, with March 2025 marking the sixth-best March in 50 years as companies and households rushed to buy goods before expected tariffs took effect. Instead of prompting conservation or preparation, the warnings seem to trigger doom spending. It seems that people weren’t just buying these items despite the crisis, but because of it.

Scale up asteroid economics and doom spending to the civilisational level, and our current predicament comes into focus. The more sophisticated doomsday calculations become, the more permission they seem to grant for excess. Humans model climate collapse with supercomputers while Amazon delivers packages by drone. Think tanks calculate nuclear risk while the United States is predicted to spend $946 billion over the next decade modernising nuclear weapons and nuclear-related systems. Tech execs build AI systems at breakneck speed with limited safety frameworks, while cryptocurrency operations burn through electricity at levels comparable to countries like Poland. The proliferation of information was supposed to democratise knowledge and save civilisation. Instead, it has become a mechanism driving it toward destruction.

I’ve spent decades in defence acquisition, always aware of a system’s drift toward obsolescence. In my 20s, I planned systems that would still be operational when I turned 50. Now I plan systems that will outlive me entirely. The work involves constant risk analysis – known risks you can calculate and develop mitigation strategies for; unknown risks you identify and quantify; and deep uncertainty, the situations that are difficult to model, and for which you lack confidence – this is what keeps you up at night. I’ve worked on countless programmes with major international defence contractors. I’ve also worked on operations in conflict zones across Iraq, Kosovo and Afghanistan. The approach stays the same regardless of location: it requires being completely impartial in auditing, unemotional, and somewhat detached.

The most absurd manifestation of asteroid economics may be SpaceX’s promise of Mars colonies

But spending years calculating how billion-dollar systems will perform under existential threats has revealed something profound about human nature to me. There’s an underlying fear in humanity, perhaps because we realise how fragile we are. Collective humanity has made extraordinary advances, but there are still enormous gaps in understanding our world, the Universe. The nature of scientific enquiry means theories can be disproved but never proven with absolute certainty, and this epistemological reality means we operate with a type of permanent uncertainty.

Every day contains unknown unknowns that no amount of analytics, prescriptive modelling or even AI can confidently predict with accuracy. There are always force majeures. The 2024 risks and threat assessments just ratcheted up that existing uncertain atmosphere. When humans face situations where they cannot know every possible outcome, they spend as if the future itself is unknowable. The analysis of risk factors in defence systems acquisition revealed how organisations – and, therefore perhaps, people – behave when they realise they fundamentally lack control over what’s coming.

The most absurd manifestation of asteroid economics may be SpaceX’s promise of Mars colonies. But for what purpose? We’ll never be able to make another planet better suited for us than this one. Asteroid mining companies plan to extract rare earth elements and benefits yet to be known from other celestial bodies; travelling to asteroids and other planets just to strip-mine them.

The film Don’t Look Up (2021) satirised this perfectly. When faced with an extinction-level comet, humanity’s response wasn’t prevention but profit extraction.

What makes our situation particularly insidious is that the better informed we become about civilisational risk, the more reckless we become. Climate scientists produce increasingly precise models of civilisation’s collapse and policy institutes calculate humanity’s extinction probabilities with bureaucratic precision. Each threat gets its probability calculation, its statistical treatment.

Meanwhile, the stock market hits new highs and SpaceX plans to build a city on Mars. Every sophisticated risk calculation seems to grant subconscious permission for recklessness. We find ourselves in a psychological trap where awareness of existential risk triggers the behaviour that creates more existential risk. Tech billionaires read climate reports then build luxury bunkers while their server farms burn energy. Oil executives fund climate research while opening new drilling sites. Politicians commission studies on nuclear vulnerabilities then increase military spending.

What if the asteroid theory itself is the trap we need to escape?

The asteroid theory explains behaviours that challenge orthodox economics. Why do people bypass savings in favour of doom spending, even though money is tight? Why do individuals make environmentally destructive choices despite knowing the consequences? Why do we consume experiences frantically, as if time is running out?

The phrase ‘You can’t take it with you’ applies to individuals, but we’ve unconsciously scaled it to our species. If human civilisation is temporary – whether ended by our own nuclear arsenals, by runaway climate change, by artificial intelligence, or by actual asteroids – then longterm resource conservation feels absurd. The existential threat pushing us reveals itself in a thousand small decisions. Each decision follows the same logic – consume now because tomorrow is uncertain.

The asteroid theory isn’t advocacy, it’s diagnosis. It explains why we behave as we do when facing civilisational-scale risks we feel we cannot control. We’ve created weapons that could destroy us autonomously, climate systems that may already be beyond our control, and artificial intelligence whose development we cannot pause. But what if the asteroid theory itself is the trap we need to escape?

Here’s where the economist Harry Markowitz becomes essential. His Nobel Prize-winning insight was elegantly simple: don’t put all your eggs in one basket. Spread risk across diverse investments. Build portfolios that can weather uncertainty. But we’ve been applying this wisdom backwards. We diversify our stock portfolios while our entire civilisation exists in one basket – a planet whose risks we’re actively multiplying.

The first step is seeing the asteroid theory’s influence on our daily lives. That extra flight despite carbon concerns, the luxury purchase despite debt, the impulse buy that serves no real need. Take a breath and a rational moment – if you catch yourself doom spending, pause and ask: am I making this choice for my future, or because I’ve given up on it?

We are free to change our behaviour and make our lives and society better

We practise sophisticated risk management in our investment portfolios while embracing catastrophic risk in our energy systems, weapons arsenals and consumption patterns. What if we applied Markowitz’s diversification logic to civilisation itself? This means building economic models that acknowledge infinite growth on a finite planet is mathematically impossible. It means slowing down production of things nobody wants. It means policies that account for how people actually behave under existential anxiety, not how textbooks say they should behave.

All those sophisticated risk calculations we commission can be used for systematic risk reduction, rather than unconscious permission for civilisational recklessness. We stop using extinction probabilities as justification for acceleration toward self-destruction. Climate reports become blueprints for action, not excuses for bunker-building.

The deepest change requires abandoning the secret comfort found in civilisational fatalism. We choose to hedge against extinction rather than betting everything on it. This means making choices – personal and collective – that assume we have a future worth preserving.

The lesson of the asteroid theory is that we need to transcend it. Only by acknowledging our unconscious embrace of civilisational fatalism can we begin to choose a different path. The alternative begins with better economic policy systems that serve long-term survival rather than short-term gains that undermine our future. We don’t have to be the asteroid that destroys our own civilisation. We are free to change our behaviour and make our lives and society better.