Religion tells us that greed is a sin, self-help books say it’s a sign of dysfunction, and we can all agree that greed is bad. Except when it’s not. As the fictional trader Gordon Gekko, the voice of 20th-century capitalism, says in the movie Wall Street (1987): ‘Greed … is good. Greed is right. Greed works.’

So which version is correct? What’s clear is, first, that we share a profound ambivalence about greed and, second, that this needs to be addressed if we want to rein in the greedy systems that are currently threatening us with everything from authoritarianism and extreme inequality to war and planetary extinction.

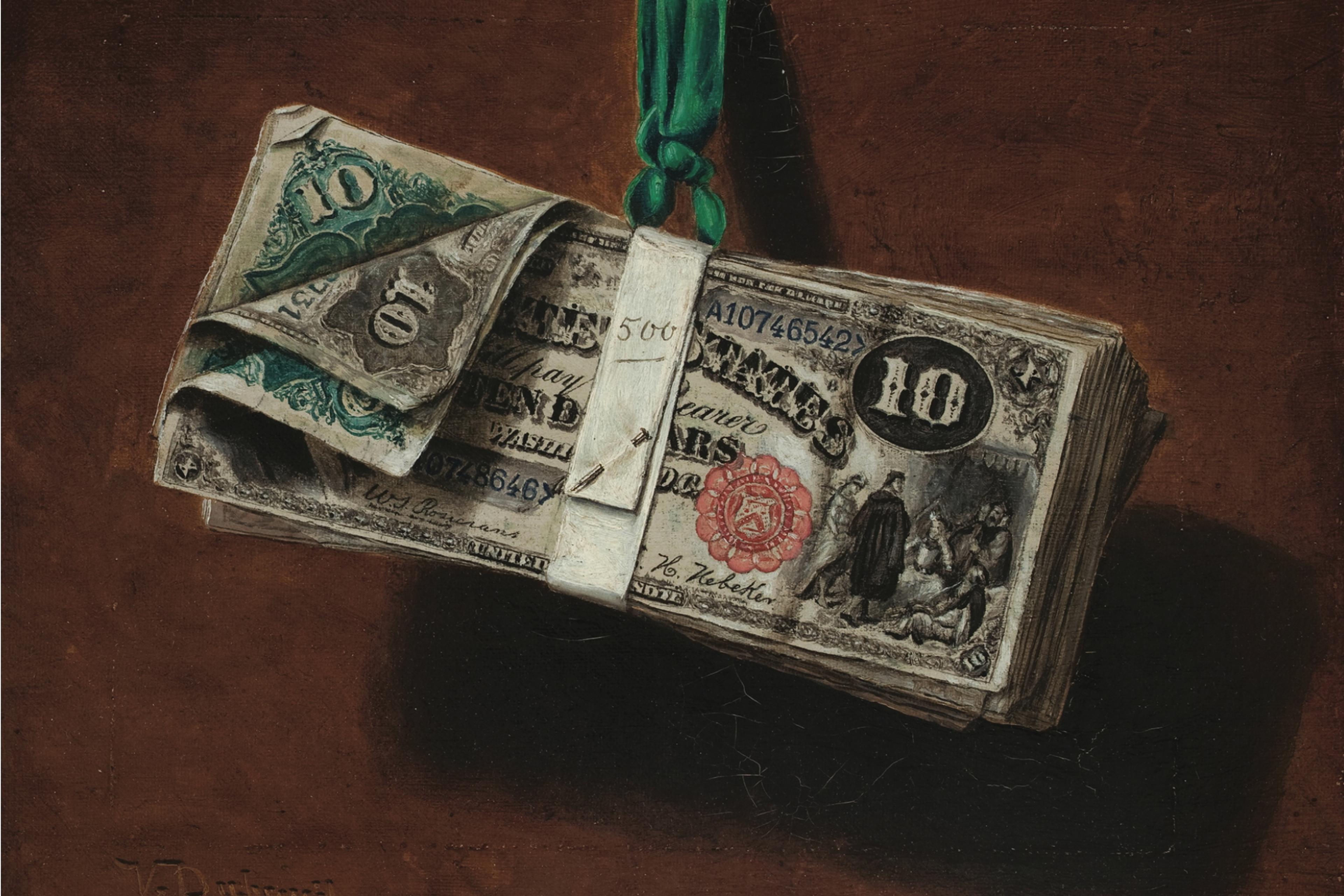

Focusing on Christianity and the United States, the novelist Norman Mailer in 2004 referred to ‘the little contradiction of loving Jesus on a Sunday, while lusting the rest of the week for mega-money.’ More broadly, a wide range of religious and philosophical critiques of greed have for centuries been running up against the stubborn reality of greedy systems, by which I mean the political and economic environments in which greed (defined as an insatiable desire for more) has been systematically encouraged, rewarded and portrayed as a good thing.

The capitalist free-market system has for a long time encouraged and rewarded greedy behaviour. Much of it was built on colonial theft of one kind or another. It’s true that greed has sometimes been constrained by ethics, by a respect for law, and even by the desire to promote ideals like democracy and human rights. But many of these constraints are being rapidly eroded. Given the longstanding insistence that greed is both bad and good, an understandable temptation has been to level accusations of greed against others. This reflex has a strong element of projection: it helps us deal with our ambivalence and preserve a positive self-image despite our own greed. But, in practice, greed accusations have often proved profoundly destructive. They also tend to reflect a magical or irrational approach to problem-solving, one that leaves greedy systems unaddressed.

Linked to this magical element has been a perverse choice of targets. All too often, accusations of greed have been redirected from the truly rich and powerful towards relatively powerless groups in society. These have included religious and ethnic groups (frequently accused of exploitative trading or lending), rebels in civil wars (whose grievances are rebranded as greed), protesters (relabelled as looters), refugees (recast as economic migrants), those on low incomes (often accused of living ‘the high life’ on welfare benefits), and defaulting borrowers (such as developing countries and homeowners whose ‘overborrowing’ was said to have fuelled financial meltdown in 2007-8).

In persecutions and even in genocide, we are faced with a deeply troubling paradox: for all the various kinds of greed that flourish amid the escalating suffering, it has routinely been the victims who get accused of greed. Thus, even as their property is being stolen or their rights removed in the service of another’s greed for money and power – be that an individual, institution or superpower – the most vehement and damaging charges of ‘greed’ have often been directed at precisely those who are being stripped of everything. This is surely the most perverse accusation of all. It serves as a warning of just how far we may depart from the truth when we decide who is being greedy. And it shows us just how dire the consequences may be.

Greedy systems have proven remarkably persistent, under capitalism, colonialism, even communism

Critiques of material greed span philosophy and religion. Plato saw money-making as the ‘appetite that exceeds all others’, proving ‘harmful to the body’ and a hindrance to the ‘cultivation of the soul’. More than 2,000 years later, Friedrich Nietzsche in The Birth of Tragedy (1872) noted that when making money takes over as the goal, people become ‘eternally hungry’, inhabiting a state of mind that is dissatisfied ‘no matter how much it devours’. In Judaism, the Torah discourages materialism as a source of arrogance. In Islam, the Quran advises against greed and the hoarding of money, stressing the need to help those in need. In Hinduism, the Mahabharata Sanskrit epic warns that ‘Just as the horns of a cattle grow old as they age, in the same way, the greed of men grows as they become richer.’ In the New Testament, Jesus stressed that a rich man’s chances of ascending to heaven were worse than a camel’s chances of passing through the eye of a needle.

But, despite all these warnings, our predilection for greed has proved notably stubborn. Indeed, greedy systems have proven remarkably persistent, whether under capitalism, colonialism or even – in a cruel confounding of Karl Marx’s more naive assumptions – communism. Greed (as Michel Foucault once said of the prison system) seems to be ‘the detestable solution, which one seems unable to do without.’

In the 16th century, Protestants were vociferously condemning corruption in the Catholic Church, including the sale of indulgences, and these accusations helped to ignite bitter religious wars. Yet even as Catholic greed was being denounced, Calvinist Protestants were suggesting that hard work and prudent saving were signs that the believer was predestined for salvation. That in turn helped to energise capitalist industrialisation, as Max Weber suggested in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1905).

Greed got a further shot in the arm when many European thinkers suggested that it could be split off from the other ‘passions’ that Christianity had condemned. As Albert Hirschman showed in his excellent book The Passions and the Interests (1977), greed was increasingly recast as rational – a sensible concern with one’s current and future interests that could helpfully rein in the sinful short-term indulgences associated with other passions such as sexual desire and lust for power. In this sense, greed was increasingly presented as a solution rather than a problem.

Our blinkers around the causes of greed have fed our very considerable shame around greed

Greed was also legitimised when a number of Protestant thinkers argued that God had created a clever system of checks and balances in which the pursuit of self-interest worked for the general good. As the Scottish political economist Adam Smith observed in The Wealth of Nations (1776), when a businessman pursues ‘only his own gain’, he is ‘led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention.’

Yet such attempts to legitimise greed encouraged dangerous blindspots – not only in relation to greed’s adverse consequences such as poverty, famine and war but also in relation to the causes of greed. Christian critiques of greed as ‘evil’ and the devil’s work had already obfuscated these causes. And now that greed was increasingly being split off and positioned as self-interest, there was a growing sense that what needed to be explained was not greed but everything else. It’s a tradition that persists today – not least in behavioural economics, which has often focused on the emotional and cognitive biases that lead us to ‘fail’ in the rational pursuit of our own interests. Again, this itself can be seen as a culturally specific endorsement of selfishness and individualism that dangerously neglects the origins of greed.

Importantly, our blinkers around the causes of greed have fed our very considerable shame around greed. We tend not to blame greed on our environments – the social pressures that push us into constantly wanting more – but instead prefer either to blame ourselves (as in the language of ‘sin’) or to point the finger at others. Yet if we could move towards a better understanding of the relentless pressures to which we are subjected on a daily basis – the pressure to work harder, to make up for failing state protection, to meet targets, to grow the economy, and the pressure to match the lifestyles we see on our screens – this could very helpfully reduce not only our shame around greed but also our associated habit of aggressively accusing others of greed. As the Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Zizek put it: ‘The problem is not corruption or greed, the problem is the system that pushes you to be corrupt.’

The shadow side of seeing success as a sign of virtue is that failure becomes a sign of vice. Shame around failure has been fuelled by the ideology of the American Dream and its international variants: once it is accepted that anyone can succeed if they try hard enough, it follows that anyone who does not succeed has not been trying hard enough. Perhaps Donald Trump’s most appealing message has been that Americans should reject diverse sources of shame, including shame for greed in the past and present, and shame for failure to prosper within a greedy system. Trump offers this escape through the promise of pride, through his own notorious shamelessness, and through shaming critics and outgroups.

Greed is today an existential threat as the planet cooks, and growing scarcities are already feeding a sauve qui peut mentality in which greed is further incentivised and legitimised. Well beyond the United States, Right-wing populist movements including the far-Right AfD in Germany have been benefiting from the offer of an escape from shame into pride. In this context, we’ve seen repeated reverence for a kind of greedom – a psychologically seductive blend of greed and freedom that resents restraint, that rebels against criticism and that feels entitled to more. A desire that then runs up against the reality of the escalating inequality it has helped to create. Meanwhile, greed and freedom seem to be for the few, with a handful of super-rich individuals becoming high-end survivalists who build shelters in Hawaii or New Zealand, or embrace the moral hazards of plotting escapes to Mars from the very planet they are undermining. In countries as varied as Brazil, India, Pakistan, China and Sierra Leone, ‘anti-corruption’ drives have also played a major role in shoring up greedy systems – not least when political opponents are selectively accused of graft. Meanwhile, as accusations of greed proliferate, ‘drain the swamp’ populist strongmen not only erode remaining constraints on greed but also fuel the narrative that politics is a dirty game that only they can fix.

We have a rogue’s gallery of leaders skilled in the murky business of deflecting accusations of greed

We probably all deceive ourselves around greed, believing that we are rationally maximising our interests and protecting our families while trying to cope with all the ‘greedy bastards’ who surround us. This reflex certainly protects us from shame. But it often serves paradoxically to protect our greedy systems – not least when our instinct for denouncing the greedy is manipulated and exploited.

Today we have a rogue’s gallery of leaders who are remarkably skilled in the murky business of deflecting accusations of greed – not only onto relatively powerless groups but also onto precisely those institutions that have tried to protect against the worst consequences of greed, whether through providing safety nets or through enforcing laws that limit the degree to which money can buy power – and hence more money.

While the Right’s focus on governments’ greed-for-power contrasts with the Left’s habit of condemning greed-for-money, it would be more productive to unmask the emerging oligarchic systems in which – as Niccolò Machiavelli showed in the 16th century and Thomas Piketty did more recently – money and power are mutually reinforcing, and greed is king. That means looking closely at the ways in which the ‘game’ of greed is rigged. Whether in post-Communist societies or mature democracies, the ‘free market capitalism’ we have been taught to revere has been profoundly contaminated by oligopoly, corruption and violence. Greed may centre on acquiring money but it is also about devouring as much as possible. The American philosopher Nancy Fraser has written about ‘cannibal capitalism’, and in diverse ways capitalism is indeed eating itself.