‘Shame on you!’ seems to come naturally for members of rival political groups these days. Shaming is also a common tactic among those who seek to promote change: it has long been a staple of human rights work, and people often hope that heaping shame in the direction of errant individuals, corporations and regimes will improve their behaviour.

Will it, though? Shame is a painful and powerful emotion, centred on the belief that one is unworthy of affection or respect. In shaming a person or group, one is generally attempting to induce some kind of shame in them. But if shaming is supposed to be productive or transformative, it’s not at all clear that it is working. In fact, in varied contexts, the shamed person or group often retaliates against the shamer, or against a hapless third party.

My own interest in shame was originally kindled in Sierra Leone when I was investigating the civil war there. During this war (which lasted from 1991 to 2002), abusive behaviour by fighters in various factions led to widening rifts with civilians. One practice involved forcing people into atrocities against their own communities; another was making them choose between types of amputation. Aid workers and other civilians emphasised that fighters were often trying to reverse earlier experiences of shame by humiliating their victims. As a rebel, for example, you could lord it over chiefs who had imposed fines or forced labour on you in the past.

I was told repeatedly that it was useless to try to shame abusive fighters into better behaviour. How could shaming work when a flight from shame had played a role in fuelling their violence? Fighters tended to react aggressively to any perceived rejection. Even at the end of the war, one aid worker told me that encouraging ex-combatants to demonstrate remorse for their acts would get you killed.

The self-righteous fury of some soldiers in Sierra Leone made me think of Shylock’s rationalisation of his own violence in Shakespeare’s play The Merchant of Venice: ‘Thou call’dst me dog before thou hadst a cause, / But, since I am a dog, beware my fangs.’ Shaming fed into bad behaviour. I noticed, however, that while civilians in Sierra Leone were naturally terrified of vicious killers and amputators, there was occasionally some small room for manoeuvre: one local aid worker who survived a rebel occupation explained how he did so by exhibiting conspicuous ‘respect’ in his daily interactions; by not shaming, he survived.

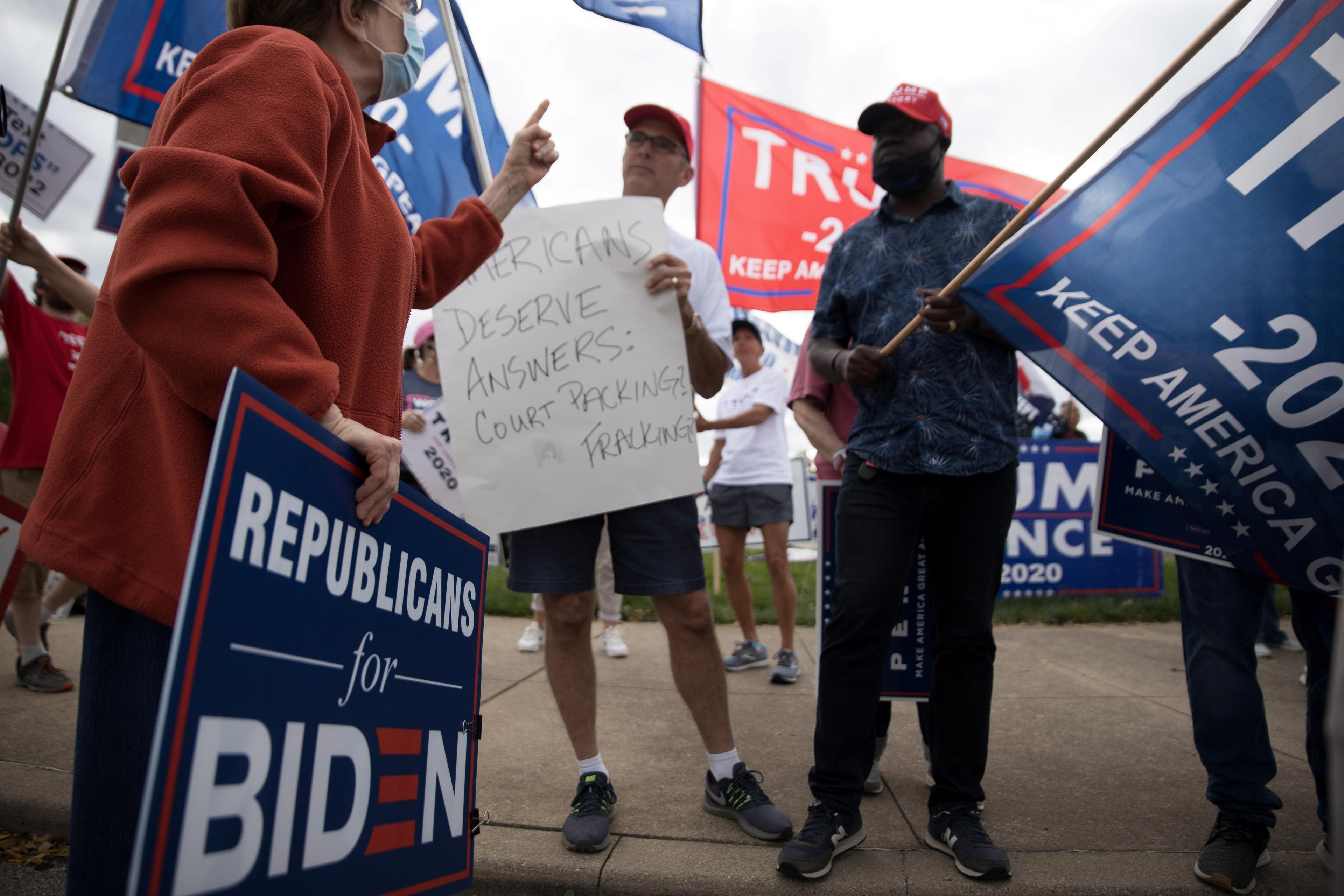

Shaming’s tendency to backfire has more recently been evident in polarised political contexts, such as in the United States, where many people who have been objects of shaming have not only failed to ‘reform’, but have dug in deeper. The righteous backlash against Hillary Clinton’s notorious claim that half of Donald Trump supporters were a ‘basket of deplorables’ should remind us that such labels can even be refashioned as a badge of honour. After widespread outrage at Trump’s referral to ‘very fine people on both sides’ when white nationalists clashed with protestors in Charlottesville in 2017, Trump cannily told a rally in Phoenix, Arizona: ‘The media can attack me but where I draw the line is when they attack you, which is what they do when they attack the decency of our supporters.’ Today, Trump insists that the multiple legal cases against him are simply evidence of how loved and feared he is. Shame not only bounces off Trump like water from a duck’s back; it is also something he actively instrumentalises to stir up the anger and loyalty of his followers.

When the Silicon Valley entrepreneur Sam Altman interviewed 100 Trump supporters after the election in 2016, many indicated that shaming them was helping Trump. One fairly typical comment was that ‘the demonisation of Trump by calling him and his supporters Nazis, KKK, white supremacists, fascists etc works very well in entrenching Trump supporters on his side.’

To understand why shaming can be so counterproductive here, we need to recognise the role that shame plays in attracting many people to an individual like Trump in the first place. In Strangers in Their Own Land (2016), the sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild’s remarkable book on Louisiana, the author linked support for Trump to the ‘struggle to feel seen and honoured’. She highlighted a perception of dwindling respect that was linked partly to diminishing job security and partly to the feeling that pride in one’s identity (religion, ethnicity, region, gender, even age) had routinely been replaced by a sense of shame, reflecting in part the perceived scorn of more urban or educated people and of the media.

Right-wing populist politics rather systematically spins shame into votes

In these circumstances, many were attracted to solutions that promised to restore respect – even when these ‘solutions’ offered few tangible benefits. Even through his own example, a conspicuously shameless politician such as Trump might offer a vicarious escape from the underlying shame of much larger numbers of people. If shame has helped to drive the Trump phenomenon, shaming him and his supporters was never likely to diminish it.

Indeed, the Right-wing populist politics that has been on the rise in the US and elsewhere rather systematically spins shame into votes. A good deal of contemporary politics has been constructed around an orchestrated escape from shame that recruits its own brand of shaming and scapegoating. As part of this, the working definition of ‘the enemy’ has been extended not only to minorities of various kinds but also to any critics. In this context, the watchword becomes something close to ‘Shame on you for shaming me!’ – a recipe for political polarisation.

Shaming on the international stage can also backfire, and it has repeatedly been put to use by unscrupulous leaders. Abusive leaders sometimes benefit from the perceived hostility of ‘the international community’. They might cast themselves as protectors of an unjustly shamed population, a tactic adopted by Saddam Hussein, Slobodan Milošević and Vladimir Putin, among others.

Given the potential for backlash and division, is shaming ever effective? Work on this subject by philosophers such as Julien Deonna, Fabrice Teroni and Krista Thomason suggests that shaming works best when a respected person directs a moderate amount of shame at someone who has temporarily departed from a shared value. Such favourable circumstances might include, for instance, the moderate shaming of a child within a loving family, though even here it could be more productive to criticise a specific action (taking us into the realm of inducing guilt) than to shame the whole person.

On a much larger scale, think of the shaming of a government for an abuse of human rights. In cases where a government has signed up to international norms, there is at least the possibility of holding it to account for values that it supposedly shares. But large-scale abuse itself would suggest that such values are not shared. The political scientist Jack Snyder has observed that human rights shaming tends to be counterproductive ‘when wielded by cultural outsiders in ways that appear to condemn local social practices’.

More generally, we can say that where shamers are seen as hypocritical, disrespectful or humiliating, where shared values are scarce, or where people are looking primarily to an in-group for validation, then shaming is very unlikely to change behaviour. Indeed, it may provoke a righteous backlash.

All of this raises the important question of why, if shaming is so often ineffective or actively counterproductive, this habit has such a hold today. The answer is complicated, of course. But there are a number of factors worth considering.

Shaming tends to serve well as an alibi. By shaming others, we divert attention from ourselves

One is the big and immediate psychological payoff from shaming. Indeed, the true point of shaming for many people might not be to change behaviour but rather to make the shamer feel good about themselves – at least in the short term. There’s a group aspect to this, too: as Myra Mendible noted in the book American Shame (2016), ‘Nothing fosters the illusion of solidarity like shared condemnation.’ Shaming, she added, ‘fills in for the spectacles that once were town square stocks and pillories’.

Social media have undoubtedly fed the collective habit of shaming, with constant electronic finger-pointing encouraged by the internet’s combination of visibility and anonymity. Online, you can publicly heap scorn on someone you don’t know without even having to reveal who you are. Digital communities partly define themselves by whom they shame. There is also money to be made by the big companies that run most of our social media. In her book The Shame Machine (2022), the data scientist Cathy O’Neil emphasises that, within what has been called the ‘attention economy’, shaming and counter-shaming work well – and profitably – in keeping people glued to their screens.

Another likely reason that shaming is so popular, despite its uncertain and often counterproductive effects, is that shaming tends to serve well as an alibi. By shaming others, in other words, we divert attention from ourselves.

There is a saying that I heard in Sierra Leone: ‘When you point the finger, three of your fingers are pointing at yourself.’ Many civilians were aware that denouncing ‘demon’ and ‘animal’ rebels played a role in obscuring, first, the multiple abuses that had helped to create the rebellion and, second, the many abuses by government soldiers. In this context, there was damaging impunity for undertrained, underpaid and often underaged government soldiers who were themselves attacking civilians. There was also impunity for international actors who fuelled the conflict. Those who participate in shaming an entity that is widely condemned often receive valuable cover.

You can also observe the role of shaming-as-alibi in US politics. In 2016, the Democrats lost the presidential election to a reality TV star with no political experience. Yet, at the time, there seemed to be only minimal introspection. Despite having been abandoned over the course of several decades by many of their traditional working-class supporters, most Democratic politicians and opinion-shapers were reluctant to ask the hard questions about their own role in the extraordinary escalation of inequality that set the scene for Right-wing (and Left-wing) populism. In this context, the Democrats’ focus on shaming Trump and his supporters acquired something of the character of an alibi. Yet if we consider a longer timescale in which Democrats themselves had a major share of political power, we may begin to imagine that the accusers had several fingers pointing at themselves.

From whichever side of the political spectrum it comes, enthusiastic shaming tends to distract from realistic and practical ways of making society better. Yet today it seems to be an integral part of a politics based on magical solutions to all-too-real crises. Shaming is the ‘feel-good’ solution that, in the end, makes nobody feel any good.