‘Today we were unlucky,’ said Patrick Magee of the Provisional IRA after the group failed to kill Britain’s prime minister Margaret Thatcher at the Conservative Party Conference in Brighton in 1984. ‘But remember, we only have to be lucky once. You will have to be lucky always.’ It’s a chilling thought, and Magee’s words are often quoted in the aftermath of terrorist attacks, seeming to sum up exactly why we find terrorism so anxiety-inducing – and so confusing.

Because a terrorist attack is unexpected – coming from anywhere, at any time – it is both diffuse and imminent, while, in its wake, the world seems a hostile, unpredictable and fearful place. Riding public transport or gathering in crowded streets feels dangerous, despite the chances of a terrorist attack happening being very low. Plus, we’re actively encouraged by the authorities to look out for ‘suspicious’ people. ‘See it. Say it. Sorted’ read those British Transport Police posters, picturing an ominous shadowy man sneaking around. Should anyone have forgotten the terrorist threat, the poster’s constant reminder ensures it’s remembered.

Strangely, it’s the threat of attack and not its actuality that erodes one’s sense of reality. Although such an attack is extremely unlikely, in a state that’s been nudged into high alert, you’re perpetually on guard – and instructed to stay on guard. It is not just random strangers that you doubt, but your own perception of reality. How can you even know what’s truly a threat, or not? The ambiguous, perennial menace of ‘terrorism’ allows our imaginations to wander, making the minimal threat seem overwhelming. The use of shock tactics by terrorists adds to this; by invoking horror movie tropes – such as beheadings – and bringing them into very everyday scenes, members of the public are encouraged to imagine themselves as characters, too, waiting for the next chaotic calamity.

Terrorist organisations don’t generally hold much power, compared with the state they’re at war with. In this situation of asymmetrical conflict, they have to rely on methods of political violence that don’t require much in the way of manpower or expense. Terrorism is, in a way, a PR exercise. It creates the impression that the terrorist organisation is indomitable, capable of subverting the status quo but, in real terms, what it possesses, and seeks to possess, is emotional power.

Terrorism, then, is performative political violence; its affect lies in its spectacular nature as much as in the violence it commits. As Brian Michael Jenkins notes in ‘The New Age of Terrorism’ (2006), it ‘works’ only if people are watching; if there’s no one to see it, and no wider audience to be terrified, it’s not terrorism. By waging psychological warfare, terrorists hope to sway political decision-making through intimidation and by heightening public anxiety. They coerce people into behaving in ways that align with their intentions, making them do things that they don’t really want to do.

And terrorism can tell us a lot about our wider relationship with security, threat and anxiety, about how our threat levels can be set by others and our sense of reality manipulated, and about how we can diffuse our own personal anxiety amid artificially heightened levels of confusion and panic. Psychological warfare isn’t limited to international relations, after all: we see it everywhere from personal relationships to ‘post-truth’ politics.

Gaslighting, in particular, relies on a similar manipulation of reality and perceived threat, albeit in domestic, personal settings. The term comes to us from Patrick Hamilton’s play Gas Light (1938), in which the protagonist, Bella, is driven crazy by her husband Jack, who disappears frequently but lies about it, creeps about their building then tells Bella she’s hearing things, and dims the gaslight in the kitchen then insists she’s imagining it. Gaslighting denotes a specific form of psychological abuse. Bit by bit, Jack persuades Bella that her perception of reality is warped, that she’s unstable, insane – all to cover up his own misdemeanours.

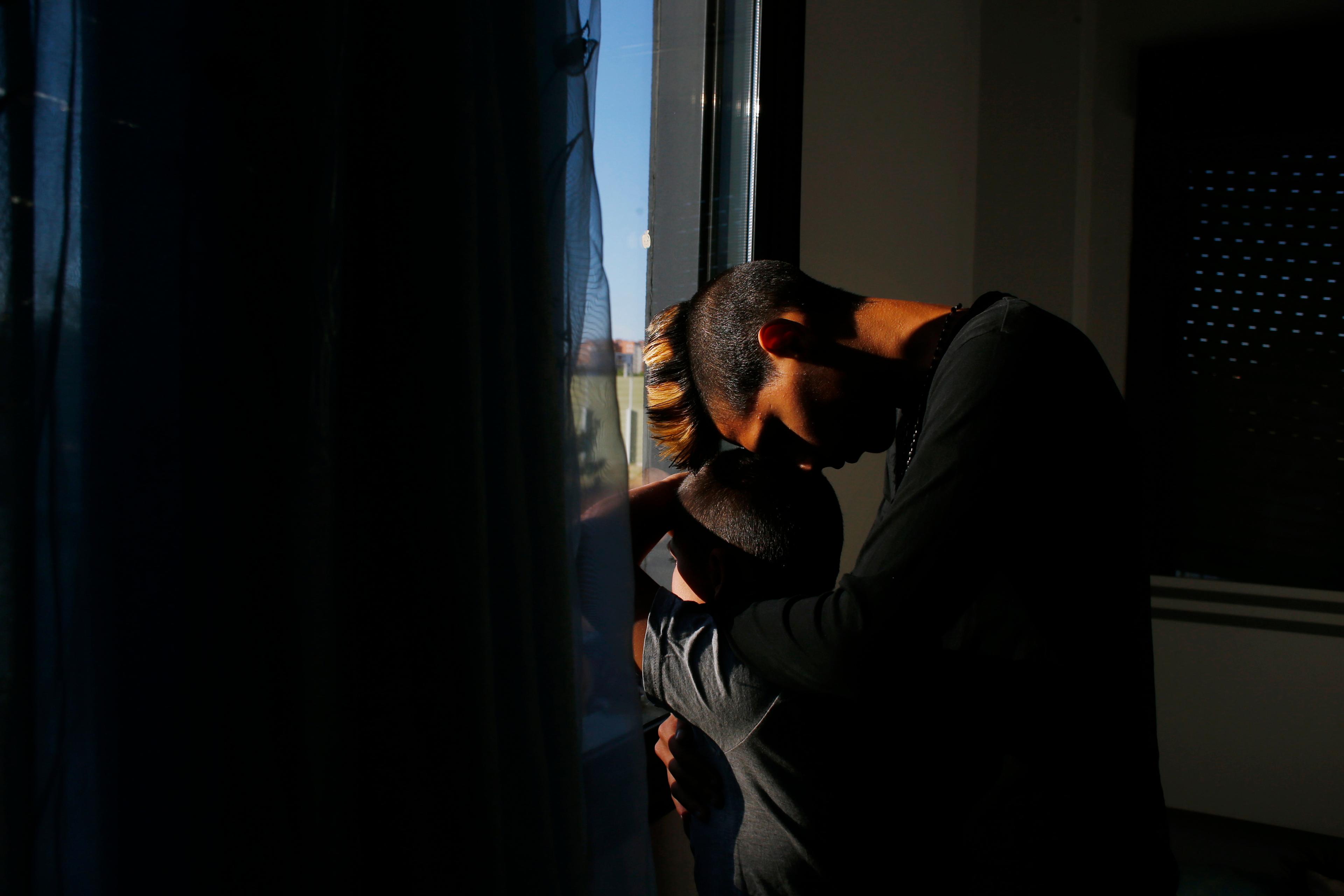

While the very point of this particular form of psychological warfare is that there’s no audience at all – only the unequal relations between two individuals and the lack of an outsider/objective perspective that this implies – its methods of intimidation, confusion and coercion are closely related to those employed by terrorists. In particular, there’s the way that one person asserts their reality over another’s and forces them into a spiral of self-doubt and anxiety. Gaslighters put thumb screws on the threat levels we perceive, through lying, issuing low-level ‘did-they-or-didn’t-they’ type threats and rewriting what we believe to be true. They make us question our personal worldviews and, perhaps more crucially, our self-view.

When we’re accused of being delusional, when we waver over whether what we saw, heard or observed was true, and when this happens over and over, accompanied by insulting language and unpredictable, erratic behaviour, our centre cannot hold. Gaslighting, like terrorism, paralyses people, depriving them of an ability to exercise judgment and agency.

In political settings, too, this subtle kind of psychological coercion and destabilisation is all too prevalent. When we talk about ‘post-truth politics’ we’re highlighting the way that political actors wield emotional power over the public through careful manipulation of the ‘truth’, not to mention outright lying. Scottie Nell Hughes, a Donald Trump supporter and CNN commentator, infamously said during the 2016 presidential election: ‘Everybody has a way of interpreting [facts] to be the truth, or not truth. There’s no such thing, unfortunately, anymore, as facts.’ When Trump churned out ‘fake news’, denying that COVID-19 was any more harmful than the flu, or insisting that he’d won an election that he’d clearly lost, he intentionally undermined evidential reality, wrong-footing his fact-bound opponents.

Gaslighting and post-truth politics are, in a sense, forms of domestic and state-institutionalised terrorism. We live daily with these contrived levels of threat and the anxiety that they stir. Moreover, those who perpetrate this ‘terrorism’ – abusive partners, manipulative political leaders, ruthless political dissenters – are conscious of the power that they accrue via these tactics, and the damage they do in wielding it over others. The challenge, for our own sanity and agency, is to fight the distorted threat and the destabilisation it causes. The challenge is to stay rooted in asserting our own integrity and stability in spite of that manipulation.

So how do we reassert our ‘selves’ and our reality when these are intentionally hijacked by the actions and words of others? Though advice from psychologists and therapists can help individual situations, we can look further afield for insights. While researching my book on emotional reactions to terrorism, I realised that much of the advice offered to government by terrorism studies experts with long experience of the Northern Ireland conflict and the more recent atrocities carried out by Al-Qaeda also applied to personal situations. In the wake of the highly problematic War on Terror, theorists such as Richard English and Louise Richardson developed strategies to advise security services on how best to deal with the continued terrorist threat. In his influential book Terrorism: How to Respond (2010), English warns against a primarily militaristic reaction and suggests meeting terror with intelligence not force. In her own book What Terrorists Want: Understanding the Terrorist Threat (2007), Richardson points out that, since terrorism is a form of psychological warfare, a psychological understanding of what some might call the enemy is key. Seeing terrorists as troubled people, not monsters, is a good start. She also suggests that we live by our principles, engage with others in collaborative counterterrorism, develop communities, settle grievances, and exercise patience and intelligence.

When English warns against the kind of militaristic response that led to such grave problems in Northern Ireland and the War on Terror, we can understand how a violent or aggressive response to gaslighting might likewise put us in more danger, opening us up to the risk of further retaliation, or redoubled assault. If one reacted to the constant lying and deviousness of a partner, for example, by having a meltdown and throwing plates around the room, our behaviour serves only to ‘prove’ our instability to the abuser and justify further abuse as ‘provoked’. The reaction is, in a way, the mark of the abuser’s ‘success’.

When Richardson suggests that we engage with other political actors and communities when fighting terrorists, we might consider the importance of developing a communal resistance to abusive behaviour and of talking to others to gain more objective perspectives on what is ‘real’. Allies, in other words, might affirm our sanity. In the case of domestic abuse, women’s refuges provide this essential structure and psychological support; their very existence makes visible the violence that goes on ‘invisibly’, behind closed doors. Much of the battle against the hidden terrorism of domestic abuse lies in making concealed deviousness transparent. When truth is concealed and distorted, simply revealing its objective reality – to ourselves and each other – is crucial.

Both English and Richardson insist that we learn to live with ‘the terrorist threat’. This point is a fascinating and difficult one. We don’t want to live with gaslighting, deception and coercion, but we need to accept them as part of living in a complex world. Abusive and manipulative people are everywhere. We can’t hope to remove them from society at large or from our own lives. But we can hope to build a psychological resilience to them, and to draw meaningful boundaries, backed up by communal support, on both personal and political levels.

The difficult aspect of the expert consensus is that we have to be prepared to be challenged – to be in the position where our sense of reality and self are thrown into doubt. While we won’t necessarily prevent terrorism or gaslighting in personal or political spheres, we can minimise their endemic psychological effects and so undermine their success, by refusing to play our part in this psychologically charged and performative emotional abuse. We can refuse to have our reality skewed, despite every effort to the contrary. While we can’t make everyone good, we can fortify ourselves against a form of abuse whose strength relies on our own fearful reaction. This is the power we have, and we must fight to keep it.